Although the authorities began issuing a limited number of exit visas at the end of 1968, the amount was inadequate to meet the demand. In1968 atotal of 238 people left the country and in 1969 ─ 3033 people. This small stream served the regime’s interest of getting rid of the active Zionists and troublemakers who had raised their heads after the Six-Day War. Instead of tamping down the interest in emigration, however, these measures only whetted the appetite by demonstrating that departure was possible.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that among the activists were some hotheads who sought to leave by circumventing the border control. There is testimony about various plans ─ crossing the border with Finland, escaping in an air balloon, or even hijacking a submarine. An activist from Rostov (now a professor at Ben Gurion University of the Negev) considered swimming to Turkey. These plans, as a rule, terminated at the preparatory stage because of the high risk and extreme complexity of carrying them out. But not all ended that way.

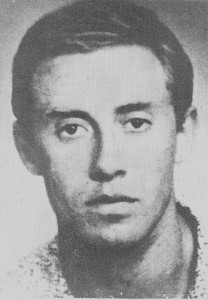

One of the attempts to cross the border illegally by hijacking an airplane was destined to mark a turning point in the struggle for freedom of emigration. The idea belonged to Mark Dymshits, a former military pilot, who understood that he could not obtain permission to leave the ordinary way. Mark had a difficult life: at the age of fifteen he lost his parents during the wartime blockade of Leningrad and was sent to an orphanage. There he suffered to the full from state and everyday antisemitism of the Stalinist period, but he was not broken.

Knowing firmly that his place was in Israel, he harbored the idea of escape for many years. Aware that he couldn’t realize his plan alone, he unhurriedly looked for companions, who were found after his meeting with Hillel Butman.

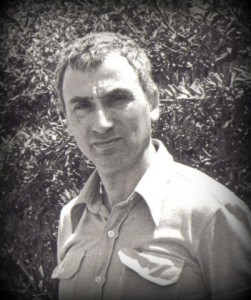

Hillel Butman wrote:

I was told about a former army pilot, Mark Dymshits, who was trying to study Hebrew on his own. I asked that an invitation to attend an ulpan be extended to him.

Mark came to me within a short time. He was then about forty years old, with a youthful face, straight dark hair…. Mark lived with his wife and two daughters not far from my wife and me, and he used to drop by to talk about his ulpan studies. Our conversation soon moved from Hebrew to Israel, and it was clear that we thought alike about many things….

One day early in December 1969, Mark and I were strolling near my house. By then he had come to trust me. Our conversation circled, not for the first time, around the problems confronted by Jews who sought to immigrate to Israel. Suddenly Mark said,

“You don’t need to fantasize; you can simply fly away.”

“How?” I wondered.

“Hijack an airplane.” Mark said calmly, and it was clear that he had long since thought it out… My first impulse was to refuse immediately. But I didn’t refuse. Mark’s crazy idea went to my head. The more I thought about it, the more it stuck. Perhaps this was the one chance I would have in my lifetime ─ if I missed it, I would never forgive myself.[1]

Butman was fired up with the idea. Indeed, doubts remained because the risk was enormous. After lengthy preliminary conversations with Dymshits, Butman decided to discuss the issue with the Committee of the Leningrad organization. The Committee did not voice strong objections but the majority hesitated. Butman was encouraged that no one objected. Dymshits subsequently began to check various options while Butman began to select participants. In February 1970 he traveled to Riga, where his only close acquaintances were Aron Shpilberg and Silva Zalmanson. Silva and her husband Eduard Kuznetsov both dreamed of leaving the country as quickly as possible. This represented a second fateful acquaintance. By April 1970 Butman had already selected about forty candidates for the planned action.

Decisions of the Committee of the Leningrad Organization were binding on all groups only if they were adopted unanimously; otherwise, decisions were binding only on those who voted for it. At the first discussion only two of the five committee members who were present voted for the plan ─ Butman himself and Anatolii Goldfeld (82-85). The others did not want to participate but promised to help if the project were implemented. Gradually, however, their attitude changed from cautiously positive to cautiously negative and then to sharply opposed. Solomon Dreizner cooled to the idea; Goldfeld stopped speaking about his participation and influenced the Kishinev group in that direction. Vladimir Mogilever spoke out against it:

…do you realize what will happen here? The Organization will be destroyed. The ulpans will be shut down. There will be searches and arrests…. They will tighten the screws and no one will be able to open his mouth… It is possible that the result [of the operation] will be the opposite ─ that Jews will no longer be allowed to work and study at the institutes, for example. A wave of antisemitism may flood the country. Think about the people you are leaving behind (Butman, p. 114).

In April 1970 the Leningrad organization held a conference at which its program and charter were discussed. Unlike the usual meetings at which one person from each group was invited, at this one there were two plus a few other people who did not represent a particular group. Toward evening when the discussions were almost over, David Chernoglaz, with Mogilever’s support, raised the issue of the operation:

Our Organization now stands at the edge of destruction. If we don’t take decisive measures today, our Organization won’t survive much longer. This is because of the activity of a member of the Committee, Hillel Butman. He is now preparing for a deed that could result in the arrest of members of the Organization, searches, cessation of all of the Organization’s activities [Butman, p.120].

Were you strongly opposed to the operation from the start? I asked David Chernoglaz.

Not completely. At first the idea made a strong impression on me. It was striking and at first glance seemed very attractive. I didn’t reject it outright.

How do you explain your sharp speech at the conference?

At that time I already understood the problematic aspect of the operation as did Mogilever. The authorities most likely knew about the organization’s existence and activity; thus the risk was too great. Moreover, we didn’t form the organization for this kind of activity. We had other tasks and interests. The discussion at this expanded meeting, the likes of which did not occur before or afterwards, represented a last desperate attempt to stop Butman. The idea was to play for time, let the idea run its course, to dissuade him or let him talk himself out of the idea.

The conference participants who heard about this for the first time were upset. Noting that according to the new charter, decisions of the conference were binding on everyone, Butman declared that he would leave the organization in the case of a negative decision and he would carry out the deed. It was then decided to return the discussion of the issue to the Committee. In the context of the dispute and the numerous efforts to dissuade Butman, the proper conspiratorial rules were not observed. Butman stuck to his guns although he was already beginning to be troubled by doubts. Finally, at one of the meetings, Mikhail Vertlib threw him a life preserver, “Let’s ask Israel. We’ll do what they say.” Everyone agreed and the day of reckoning was delayed to everyone’s satisfaction.

Butman and Mogilever, through Rami Aronson, a Norwegian citizen who was then in the USSR, sought the Israeli government’s approval for three actions: hijacking a plane, an open demonstration in Leningrad, and a closed press conference for foreign journalists. Nehemia Levanon…dealt with this issue in Israel. A. Blank passed on Levanon’s negative answer to Mogilever in an international call from Israel to Leningrad. Because the phone was tapped…they spoke in code, using the language of a medical consultation about prescribing Butman’s mother-in-law three different drugs. The first two (hijacking and demonstration) were definitely out of the question. The third was “up to the discretion of the local doctors.”[2]

Nehemiah Levanon was categorically opposed to the plane hijacking and regarded it as a provocation, recalls Eitan Finkelshtein. I must confess that I agreed.

Were you asked to participate in this, Eitan? I asked.

I suggested that they shouldn’t participate, replied Eitan. And they promised me. You understand, life is a complicated matter. If a person jumps off the tenth floor, he could survive and become a hero, but 99 percent are killed. At the time it looked like a provocation and I was almost certain that the “organs” [KGB] were pulling the strings one way or another…. This is not to cast any suspicion on Kuznetsov or Dymshits. The world was struggling against airplane hijackings.

The answer from Israel was thus categorically negative. Butman submitted to the verdict, reported this to the other candidates for operation “Wedding” (the code name for the plan), and withdrew from their group. Far from all of the participants, however, were willing to renounce the idea.

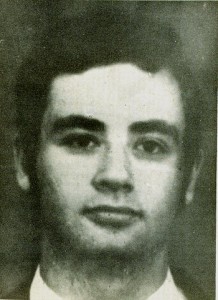

Mark Dymshits, Eduard Kuznetzov, and Iosef Mendelevich became the driving force behind the operation. Even when Kuznetsov suggested delaying the plan for a year, the cold-blooded resoluteness of Dymshits and the group’s determination to try their luck prevailed.[3]

On June 15, 1970, twelve Jews, mainly from Riga, attempted to hijack a plane. They planned to fly to Sweden and from there to Israel. They targeted a small, twelve-seater AN-2 plane that flew a route from Leningrad’s Smol’nyi airport to the town of Priozersk, near the Finnish border. On day “X” they bought up all twelve tickets for the flight.

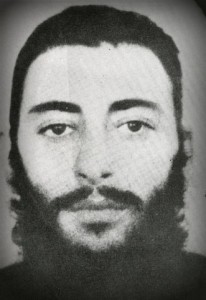

According to Mendelevich’s description of the plan, “After landing in Priozersk, when the pilot would open the door of the cabin, two of our people would stand on both sides of the door and tie his hands. The second pilot, sitting with his back to the exit, wouldn’t manage to draw his revolver ─ he would also be bound.”[4] Mendelevich continued: “My task was to help Mendel Bodnia, a wrestler, tie up the first pilot; Izrail’ Zalmanson and Edik Kuznetsov were supposed to deal with the second pilot. I wrote a ‘Testament,’ about the reasons motivating us to take this desperate step. If we perished or were arrested, the testament was supposed to be publicized.”[5]

The hijacking group did not manage even to board the plane. They were all arrested on the tarmac. The chekists put on an impressive show. The unarmed group was detained with the use of military units and guard dogs.

The “Testament” stated:

We are making an attempt to leave the territory of this state without requesting the permission of the authorities. We are among those tens of thousands of Jews who for many years have been stating our desire to be repatriated to Israel to the appropriate bodies. Invariably, with monstrous hypocrisy, perverting universal, international, and even Soviet laws, the authorities deny us our right to leave. They insolently declare that we shall rot here and never see our homeland…. We are moved by the desire to live in our motherland and to share its fate.[6]

A postscript to the “Testament” contained a request to care for relatives and dear ones in case of failure.

News of the arrests spread, sowing anxiety among the activists’ ranks. On the one hand, the hijacking attempt highlighted the catastrophic situation regarding emigration from the country: law-abiding people had been so harassed that they were willing to undertake such a desperate step even at the risk of their life. On the other hand, even had the operation succeeded, it would have solved only the participants’ problems, leaving relatives, friends, and comrades to bear the brunt of the blow from the enraged KGB. The whole world was struggling against plane hijackings, a crime that was unconditionally and categorically condemned. The Soviet punitive organs would have had the ideal pretext to conduct reprisals.

The sentencing in the trial changed the situation. Two death sentences were handed out for an attempt in which no one was harmed and that was averted before the hijackers boarded the plane. It was clear to everyone that this was not a matter of punishing criminals but of a reprisal against those who wanted to emigrate from the USSR.

“Vasilii Tolstikov, the first secretary of the Leningrad regional party committee, was evidently a dyed-in the wool antisemite,” commented Eitan Finkelshtein. “The punishments were monstrous! Had there been no death sentences, if the terms had been moderate, say three to five years, then everyone would have been quiet and it would have been a major failure ─ we would all have been hounded and perhaps even rearrested.”[7]

“According to information derived from various sources,” wrote Eduard Kuznetsov, “it was precisely Tolstikov (who, like any person near the top of such an important area as Leningrad, was striving to reach the very top of the party hierarchy) who insisted in the Kremlin on the need and desirability of the harshest reprisals against those who had attempted to flee the USSR in order to crush the emigration movement, mortally frightening its participants (46 people in various cities were arrested in cases linked ─ sometimes very tenuously ─ with ours). He and those with him failed… Tolstikov was let go and shipped out as an ambassador to China, and then, even worse, to Holland.”[8]

The chances that Operation “Wedding” would succeed were very minimal.

As someone who had already served time and not the stupidest person on the planet, I understood, of course, that it was a hopeless matter, recalls Kuznetsov.[9] We had sixteen participants. In order to reach this number, it was necessary to speak with hundreds of other people. Those who rejected the idea were not obligated to keep the secret and they gossiped and whispered. Even those who were involved in the plan talked ─ human nature is such that a person can’t keep quiet ─ whether to a friend or a lover…. A leak was inevitable.

Why did you go for this despite everything?

Let me tell about myself first, and then if it’s interesting, I’ll sketch the others’ psychological motivation and situation. My situation was rather complex. I had just served a seven-year sentence for dissident activity and was under administrative supervision; I was being followed. If I would be even minimally active, they would lock me up for practically nothing. For me the issue thus was whether I would be arrested for a deed or simply for no reason.

I pride myself on the fact that at the time I already perceived the trend that later led to détente. I was in contact with important figures. They believed in an old theory: “We understand that everything is collapsing, that they are all scoundrels, but decent people need to join the party and change everything from the inside.” At the same time these people understood that the economic situation was disastrous. The Soviet Union was ripe for détente, that is, in exchange for hard currency, grain, know-how and all the rest, the regime was prepared to backtrack on some issues. It wasn’t clear on which issues they would be willing to backtrack; perhaps if we pressured them on the issue of emigration, they would make concessions. That was approximately my thought and I guessed right.

But Edik, at that time the West was afraid of the Soviet Union and Israel was doing everything possible not to antagonize it….

Of course. But the writer Vladimir Maksimov once told me that when he was drinking with Baibakov, the former director of Gosplan [the State Planning committee], and yelping about the Soviet regime, Baibakov said to him: “C’mon! You don’t know the half of it!” I went out on the street and looked: the streetcars were running, the windows were lit, peoples’ televisions were working, and I thought to myself, how, indeed, does all this manage to work? Everything was on the skids, everything! The authorities understood very well that they were ripe for détente, for concessions. Of course I can’t say that I was a hundred percent certain but I did have this theory and I propagandized for it: “Guys, if we press, there is a chance.”

The regime, of course, drove us into a corner. People applied for exit visas several times and received refusals, and they did not have a ray of hope left: there was no work for them and they had been driven out of the institutes. A group of people assembled around us that wanted action, not discussions. They harbored a certain illusion about me, thinking, “he’s experienced, he knows how it’s done.” But, in fact, what did I understand? Penson [a participant in the hijacking plan), it seems, expressed the general feeling about the regime: “Let them arrest us because afterwards, we’ll probably be released.” It was from a sense of hopelessness.

Everything was uncertain…. We all went to the airport…later from the case file we learned that a whole border regiment was sent there. Two or three soldiers were positioned behind every bush. We pretended that we didn’t notice them and they also averted their eyes. We knew what we were getting into but human nature is such that one doesn’t want to acknowledge fully that perhaps something is wrong… after all, we had also been tailed earlier when we made test flights and we hadn’t been arrested. They would again accompany us to the plane, think that this was another simulation, would inform the necessary authority, reporting that they flew off and that would be all…. Knowing how the Soviet system works, this kind of outcome was not impossible.

Looking at things soberly, I knew that they would lock us up. But if it was done quietly, we could be tried behind closed doors and no one would know about it. It was important for us that there be a scandal and in this respect our interests coincided with those of the KGB. It was also important for them to create a commotion with our arrest in order to point out: “Look at these supposed fighters for freedom of emigration! In fact, they are just ordinary bandits.”

What about the possibility that the West could be frightened by an attempt to hijack a plane?

Well, Butman sent a question to Israel in order to get out of it. Israel could answer only “no.” They didn’t know; after all, it could be a provocation.

The team of “hijackers” was tailed closely. In April KGB chairman Yuri Andropov reported to the Central Committee of the CPSU that the Leningrad Zionist organization together with Riga nationalists were planning some secret operation about which they intended to ask for Israel’s opinion. “The Committee for State Security is taking measures to verify the information received and to prevent the realization of possible hostile actions on the part of Jewish nationalists,”[10] affirmed Andropov.

Some secrecy! Semyon Ariia, Mendelevich’s lawyer at the trial, testified, “The degree of conspiracy is reminiscent of the Odessa joke about the spy ‘who lives one floor up.’ As far as I recall, information in the case file stated that in Riga people were asked on the street whether they were interested in joining. In Leningrad the children of the travelers said farewell to their classmates.”[11]

The KGB prepared a strident trial. It wanted to demonstrate the Soviet state security organs’ effectiveness to the Central Committee and the entire world and also to shut the mouths of “all those fighters for the Jews’ rights” in the West by showing what kind of people they were defending.

During an investigation, Mendelevich wrote, strange things happen: courageous and close-mouthed people suddenly become timid and talkative, even when it would be possible to remain silent without especial difficulty. In the labor camp people frequently discussed this “phenomenon of complaisance.” It has even been suggested that chemical preparations are added to the prisoners’ food that weaken their will. In my opinion, it’s much simpler. Fear of the KGB, which has been instilled in the Soviet citizen from childhood, breaks him/her even before the interrogation…. And the prisoner is faced not with a heroic open struggle but with the prosaic, daily routine of the investigation, which requires stubbornness and resistance.

This all takes place in the context of complete detachment from ordinary life. One must not give in, not forget the reason for following this dangerous path. Without faith in the justice of your cause, you lose the sense of reality…. You are without newspapers, letters, or news from home. And perhaps, everyone forgot about you a long time ago. You are alone. One on one with the investigation.[12]

At the beginning of November, when the investigation in the hijacking case was close to completion, a real plane hijacking occurred in the Soviet Union. Two Lithuanians named Brazinskas, a father and son, escaped from the Soviet Union, killing a stewardess and wounding two pilots in the process.

“Now things will really be hot for you!” remarked Mendelevich’s investigator at an interrogation. “He knew what he was talking about,” wrote Iosef. “We had to be punished harshly to serve as a warning to dissuade others from attempting a plane hijacking. In connection with the stewardess’ murder, our trial was delayed for a month and set for December 15.”[13]

Ariia later described the legal side of the case:

The participants in Operation Wedding were charged with attempted treason (attempted escape), an attempt at a very large theft (hijacking a plane), and anti-Soviet agitation (their “Appeal” with its protest against political antisemitism). Before the trial the defense team was assembled and Sokolov, the chairman of the Leningrad collegium of lawyers, informed us of the recommendation of the “directive” organs that we shouldn’t contest the charge of treason. Insofar as our clients did not acknowledge themselves guilty of treason, this recommendation was equivalent to a proposal to betray the defendants. Both Moscow lawyers (Yu. Sarri and I) therefore ignored the Leningrad bosses’ recommendation and at the trial we conducted ourselves honorably. The local colleagues had to submit to the authorities. The order from above had sunk in so deeply that even after the prosecutor in the trial rejected the charge of treason against Bodnia (he was trying to get out to be with his mother), his lawyer asked us in distress what he should do ─ could he accept the prosecutor’s opinion on this matter or should he disagree with him and admit the charge of treason… I shall not dare to condemn them; they had families….[14]

The trial took place from December 15-24,1970 inan old building on the Fontanka that housed the Leningrad municipal court. The first ring of police barriers was placed about one hundred meters from the building; the second and third were inside. People were admitted on the basis of special passes issued by the party district committees. The huge courtroom, which Ariia described as gloomy and poorly lit, was full of a carefully selected “public.” The relatives of the defendants sat silently, apart from the others. The scenario and the outcome of this performance had been determined neither within the building’s walls nor even in Leningrad. The defendants’ courageous behavior made an impression even on this specific audience, which did not exude the atmosphere of hatred that was usual in such cases.

On December 21… the court announced the verdict. Kuznetsov and Dymshits received the most extreme punishment ─ the death sentence. In view of the particular circumstances ─ the plan was not carried out and there were no consequences ─ the sentence seemed monstrously cruel. The remaining defendants received long sentences ranging from ten to fifteen years of imprisonment. Only Bodnia received six years.[15]

The Soviet regime once again cruelly bared its teeth, but this time it tripped up. Instead of creating fear in the Soviet Union, it unleashed a wave of protests. An even larger wave arose in the West.

On December 23,1970, in distant Spain, Basque terrorists who were responsible for the deaths of several policemen were sentenced to death. Demonstrations demanding the rescinding of the death sentences for the Basques and for Dymshits and Kuznetsov swept over Europe.

Do you know the role that Generalissimo Franco played in your fate, I asked Kuznetsov?[16]

Izho Rager told me not long before his death that Golda Meir sent him on a mission to Franco and Rager succeeded in convincing him to pardon the Basques.

In Europe demonstrators called for the repeal of the sentences of capital punishment. Rager, as I wrote in my recent book A Step to the Left, A Step to the Right [Shag vlevo, shag vpravo], attained a meeting with Franco as Golda’s personal representative. “Once,” Rager said to the generalissimo, “you rendered an invaluable service to our people when you didn’t hand the Jews over to Hitler. Do it again ─ pardon the people whose hands are stained with blood in order to save those whose hands are clean.” Franco revoked the death sentence and thus put Brezhnev in a foolish position, making it appear as if the communist was less humane than the fascist.

I personally had mixed feelings at first with regard to the hijacking attempt. It didn’t seem to me like an intelligent move. But after the death sentences all doubts were dispelled ─ ours was a just cause. On December22 agroup of Sverdlovsk Jews gathered at Valera Kukui’s apartment. After closing the doors and sealing the windows, Valera said quietly, “The signal has come from Moscow! They are expecting a letter from us about the sentencing.” The signal came from Eitan Finkel’shtein but his name was not mentioned.

We understood what this letter would mean for all of us. In publishing an open protest, we would pass the point of no return. When Valera and I were alone, he asked, “Do you want to write it?” “I’m willing.” “I am too,” he said. “Let’s do the following: let each one write his version at night and in the morning we’ll combine them.”

“Let’s go.”

That night I didn’t close my eyes.

At eight in the morning I went to Valera with several scrawled pages. He read them and said, “Good, let’s take your paper as the basis and I’ll just edit a few places and add some ideas.”

Valera made several corrections and asked, “Do you want to sign first?” I was willing. “I also want to,” he said. “Let’s toss a coin.” He won. Our first letter was rather sharp and we realized that he would endure the strongest blow because his signature was first….

We both signed, listing our home addresses and telephone numbers. Then the others came and signed ─ Volodia Aks and Boria Rabinovich joined the signatories ─ and with that our two groups united. Boria Rabinovich set off to deliver the letter to Moscow.

I hold this, our first letter, in my hands, the yellowed pages that miraculously survived the refusenik life; they are already thirty-five years old. I can’t count how many such letters followed, but this first one is the dearest of all.

It was addressed to the Soviet leaders Brezhnev and Podgornyi, and the Supreme Court of the USSR:

…The sentence that was delivered is unjustifiably cruel and inhuman….It recalls the black days of the cult of personality [under Stalin]….

Among the convicted…there were no criminals hiding from Soviet justice. They were not armed and could not represent a threat to the life of the passengers or plane crew. Their action was aborted at the very beginning and, in essence, there was only a plot but not an attempted hijacking, not to mention a hijacking itself.

The sole reason inducing these people to consider hijacking a plane…is the absence of any possibility for departing…by legal means…. The majority of the defendants…received unmotivated and illegal refusals… This is an act of despairing people who were impelled to try it because of the authorities’ failure to observe their own country’s laws….

Millions of Jews throughout the world and in the USSR harbor sincere sympathy for Israel, consider it a symbol and realization of the Jewish people’s national revival…. It’s not difficult to imagine…the situation of a person…who is striving to participate in the process of national revival… but is prohibited by the official authorities from doing so. What does the regime want to attain? Intimidation or a just solution to the problem? Does it want to drive the disease inward or eliminate its causes?

Implementing the court’s sentence will inevitably leave a permanent stain of cruelty on the official garment of Soviet justice…. We appeal to you, the executors of the supreme power and legality of the Soviet state, with a resolute demand to revoke the death sentences of Dymshits and Kuznetsov.

We demand full adherence to the constitutional rights and guarantees of Soviet citizens, including offering those who wish it the immediate opportunity to depart….

We considered it necessary to send a copy of this letter also to the government of the State of Israel with a request, if it considers it necessary, to inform people worldwide of its content.

The protest letters were read aloud on Israel radio. There were many of them ─ Andrei Sakharov and Valerii Chalidze were among those who spoke up. Franco subsequently repealed the death sentence of the Basque terrorists ─ to us this seemed like a wonderful coincidence…. We waited, holding our breath: wouldn’t the regime now come to its senses?

A few days later the death sentences of Dymshits and Kuznetsov were revoked. We were proud and happy…. We were already being tailed but we reveled in the victory in which, it seemed to us, we had played some role.

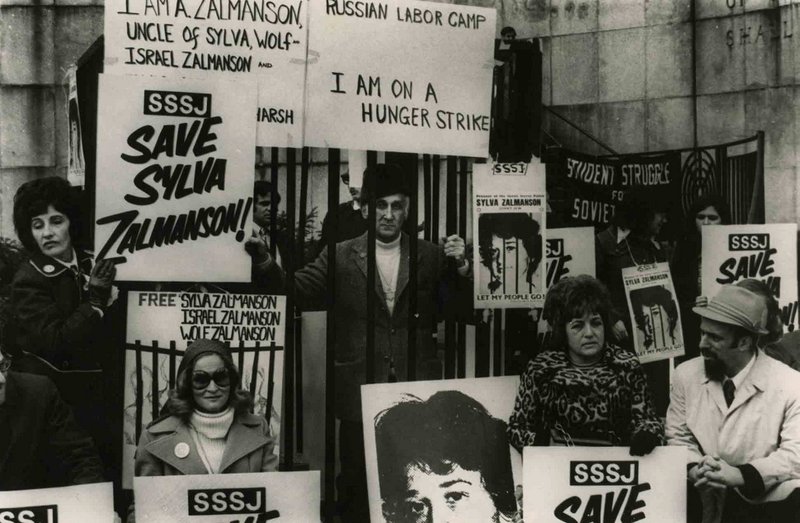

Protest and Hunger strike by Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. Sitting right: Lynn Singer and Jacob Birnbaum, co SSSJ.

At the time we were not aware of the forces set into motion by the Leningrad trial. “In 1973,”Kuzentsov told me,[17] “when Silva was released, she declared that she would not leave before they gave her a meeting with me. I was brought to the Lefortovo KGB prison, where I was summoned to a conversation with a general named Ivan Ivanovich Ruderman. He said, “Had we known what would happen, we would have let you fly away…and then you would have been ordinary plane hijackers and we wouldn’t have had to get out of this mess of endless protests in the West….”

The lawyer Semyon Ariia gave the following description of the appeal process:

Having discussed with Mendelevich and his family the next steps in appealing the sentence, I returned in a depressed mood to the hotel, and my colleague and I prepared to return to Moscow, but we weren’t able to leave. At 11:00 p.m. the phone rang and Judge Ermakov suggested that we come to him urgently. I objected: I had a train ticket in my hands and we were about to leave. “We’ll exchange the ticket,” Ermakov said. “Don’t worry.” When we arrived in bewilderment at the judge’s office, all the other lawyers were already there. Ermakov said, “I am informing you of the following: the Supreme Court will hear the appeal of our case in three days. Therefore tomorrow, on Saturday, and Sunday the KGB prison and the judges’ office will be working for all of you. In these two days you must manage to study the protocol of the court session, submit your comments on it, help the convicted people draw up their appeals, compose and print up your own, and hand them in. On Sunday evening the file will be sent by plane to Moscow and reviewed by the Supreme Court on Tuesday. Are there any questions? I can’t explain or understand anything,” added Ermakov, “but that’s the order from there” and he pointed to the ceiling.

The following morning I had barely arrived home from the train station when the phone rang and our head lawyer Bykov said to me, “Senia, quickly call Smirnov. He is in and he is waiting for your call.” (L.N. Smirnov was the chairman of the Supreme Court of Russia. I was again astonished. “It’s now eight o’clock in the morning. It’s unlikely that he started working at that hour!” “Call,” Bykov responded, “he’s at work; he woke me up at seven.” Indeed, Smirnov was in. When the secretary connected us, his characteristically resonant voice boomed out, “Comrade lawyer! I know that you have just arrived. But I personally spent the whole night reading the file with which you are familiar. It does not have your appeal. Instead there is what you call a ‘leaflet.’ Therefore you must come here and by evening please prepare a normal appeal. You have thirty minutes for morning tea. Is everything clear?” The next day, December 28, I again had to get past the double encirclement in order to reach the room where the review of our appeal would take place. On the back bench sat Academician Sakharov, with the three separately pinned stars of a Hero of the Soviet Union (they had not yet been taken away).

In the corridor the familiar prosecutor met me and I asked him what was happening and what to make of all this. He explained that U.S. President Nixon phoned Brezhnev on a direct line and made a personal request not to ruin the Americans’ Christmas holiday and by New Years to rescind the death sentences in the case! Brezhnev then turned to the appropriate people here with the same request. When they timidly began to stutter that, so to speak, this would be a violation of the legitimate sentences, Brezhnev regarded this as tactless and didn’t even start to listen. It had to be carried out. “So now you will have the revocation of the death sentence according to Nixon rather than according to the Criminal Code,” concluded my acquaintance.[18]

When I asked Jerry Goodman, the executive director of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry in the U.S., how they were able to defend potential airplane hijackers in the western media and in the corridors of power he replied:

I did not use the work “airplane hijacking” because according to the law it was not a hijacking…. One of the basic things in propaganda is knowing what you are doing and being careful how you formulate this matter. Airplane hijacking has a precise definition. The plane must be in the air and the plane and the passengers have to be hijacked together. They had their own pilot. Yes, they were stealing state property. They could have stolen a truck or something else. The fact that you will fly in the given case is not significant. This was not a plane hijacking in the classical sense of the word. We learned how to formulate this, which was important. When this happened and THEY began to arrest young people in various cities, the American Conference[19] met again and declared that we could not continue to operate as we had previously. Then in December was the trial and Dymshits and Kuznetsov were sentenced to death. Then the American Conference urgently convened in Washington a large meeting of the heads of organizations; a thousand people attended it. We formed a delegation and organized a meeting with President Nixon. I was not a member of this delegation as I was too young and insufficiently important at that time. As a result they helped to bring about the revoking of the death sentence; instead the fellows received fifteen years each. The Conference met again after this and the Lishkat Hakesher (another name for Nativ) declared that now we ought to do a lot more than we had until then. The leadership decided to form a permanent operating group. In 1971 the National Conference on Soviet Jewry was formed with an office, its own budget, and staff…. The release of Dymshits and Kuznetsov was one of the highlights of my life but that is already another story….[20]

After the court review the sentences were the following:

Eduard Kuznetsov, Mark Dymshits, and Yurii Fedorov ─ fifteen years each;

Aleksei Murzhenko ─ fourteen years;

Iosef Mendelevich ─ twelve years;

Silva Zalmanson, Anatolii Altman, Lev Knokh; Boris Penson; and Vol’f Zalmanson ─ ten years each;

Izrail’ Zalmanson ─ eight years;

Mendel’ Bodnia ─ four years.

Many from the group would be released early and given exit visas to Israel. Silva Zalmanson was released in 1974 inexchange for the Soviet spy Yurii Linov, who was caught in Israel.[21] Kuznetsov was released on April 27, 1979.[22]

After the Leningrad trial, the aliya struggle entered a new, more active phase of world-wide Jewish mobilization.

[1] Hillel Butman, From Leningrad to Jerusalem, Benmir Books, Berkeley California, 1990, pp. 76-78. Further references will be included in the text.

[2] Interview with Butman, in Morozov, Documents on Soviet Jewish Emigration, n. 6 to Document 17, p. 85.

[3] Butman, From Leningrad to Jerusalem, p. 150.

[4] Iosef Mendelevich, Operatsiia Svad’ba (Kiev: Midrasha Tsionit, 2002), p. 62.

[5] Mendelevich, Operatsiia Svad’ba, p.203.

[6] Excerpt from the text “Zaveshchanie,” in the archive of the site “Zapomnim i sokhranim” (in English Remember and Save ─ http://www.angelfire.com/sc3/soviet_jews_exodus/English/Memory_s/Memory.shtml).

[7] Eitan Finkelshtein, interview to author, June 18, 2004.

[8] Eduard Kuznetsov, Shag vlevo, shag vpravo…, (Ivrus, 2000), p. 6.

[9] Eduard Kuznetsov, interview to the author, May 18, 2004.

[10] Morozov, Jewish Emigration…, Doc. 17, p. 85.

[11] “Samoletnoe delo,” http://www.ijc.ru/istoki10.html.

[12] “Samoletnoe delo.”

[13] Iosef Mendelevich, Operatsiia svad’ba, p. 109.

[14] Semyon Ariia, “Samoletnoe delo.”

[15] Ariia, loc. cit.

[16] E. Kuznetsov, interview to author, May 18, 2004.

[17] Eduard Kuznetsov, interview to the author, May 18, 2004.

[18] “Samoletnoe delo” http://www.ijc.ru/istoki10.html

[19] An organization representing 24 Jewish organizations that was founded in 1964.

[20] Jerry Goodman, interview to the author, February 19, 2004.

[21] E. Kuznetsov, Shag vlevo, shag vpravo, p.7.

[22] Non-Jews Fedorov and Murzhenko, served their entire sentences.