The circles for learning Hebrew were called “ulpans” after the name of the courses for Hebrew language study for new immigrants in Israel. Ulpans played an exceptionally important role in refusenik life. While studying the language, we prepared for life in a new country and became acquainted with elements of its religious and secular culture, its songs, geography, history, and so forth. This was the main task of the ulpans. In addition, one learned there how to request an invitation from Israel and to submit documents for an exit visa and how to prepare for either departure or refusenik life. In the ulpans one made new friends, learned how to convey information to the West or Israel, how to conduct oneself with the police or KGB, and much else. Moreover, through friends and relatives of the ulpan students, a network was formed that linked the refusenik community with Jews beyond it.

Strange as it seems today, instruction in the Hebrew language was prohibited in the Soviet Union starting in 1919, although islands where knowledge of Hebrew was retained to some degree remained in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and the areas annexed during World War II ─ the Baltic states, Bessarabia, and the Carpathians. Thus, people who had studied Hebrew in a heder, Jewish gymnasium (high school), or in courses organized by the Zionist movement were still living in those areas. In other areas, for example in Leningrad, “in 1970 over one hundred people studied Hebrew and history in twelve ulpans in homes.”[1]

It was also possible to meet people with a good knowledge of the language and culture in the central regions of the Soviet Union. Some were Jews who had lived many years in mandate Palestine and returned to the Soviet Union because of communist convictions or were expelled by the British for the same reason. Their Hebrew was lively and natural. In Moscow this was the case with Izrail Mints, Avigdor Levit, and Leah Trakhtman-Palkhan. Soviet reality cured them of excessive enthusiasm for communist ideas.

Izrail Borisovich Mints (1900-1989), a man with an amazing fate, was an activist in the Zionist Hehaluts movement in his youth. He was arrested for the first time in tsarist Russia when he was undergoing training in a Hehaluts work battalion. At the time he was under twenty years old. His second arrest occurred in 1923, when he was secretary of Hehaluts in Belorussia. He was charged with ties to the international bourgeoisie and to Zionists striving to overthrow the Soviet regime. “In the second instance I was under the threat of capital punishment,” he recalled.[2] He succeeded in making his way to Palestine, where he became one of the founders of a kibbutz in the Jordan Valley. He then returned to the USSR in 1932 and was arrested again in 1937. “I was accused of counterrevolutionary activity, of having been sent to the USSR as an emissary of the Jewish Agency, and of being in charge of agents in several Soviet cities … of having crossed the border with Poland illegally to set up Zionist links. I was tried by a special commission [OSO in Russian] and sentenced to five years of forced labor camp and permanent settlement in the Vorkuta region,” he recalls.[3]

Rehabilitated in 1953, Mints returned to Moscow and began to re-establish his Zionist connections. An active, educated person, he contributed considerably to raising the national consciousness of Soviet Jews: he organized Hebrew ulpans and taught the language himself; he translated Israeli literature into Russian and wrote articles that were disseminated in samizdat. Mints loved Israel passionately and was able to transmit this love to his students. In 1973 he received an exit visa and went to Israel.

Leah Trakhtman was expelled by the British authorities from mandate Palestine to the Soviet Union ─ her place of birth ─ for excessive communist activity when she was still a minor. In 1956 Leah obtained permission to visit relatives in Israel and returned to the USSR firmly determined to move there with her family. Her sons Moshe and Israel were among the founders of the most effective school for Hebrew instruction in Moscow.

Among the Hebrew teachers in the late 1960s were some who had learned Hebrew rather well on their own. “In Moscow,” recalls Vladimir Prestin,” Aryeh Shinkar, Aryeh Rutshtein, and Moshe Palkhan were teachers. There were no ulpans then, just private language instruction. We all studied with Aryeh Shinkar. That was in 1969….”[4]

Despite the negative attitude toward everything Jewish in the Soviet Union, unexpectedly, in May 1963, the Hebrew-Russian dictionary of Feliks Shapiro was published. The editor of the work and author of an excellent grammatical sketch was the well-known Semitics scholar and professor at Moscow State University, Bentsion Grande. The dictionary was sold out in a few days but “before entering the store, interested people would pass by the display window several times; who knows what thoughts entered their minds!”[5] In Soviet times, we had learned that “nothing is done just like that”: some feared that it was a provocation that could land them in trouble; others began to think that “perhaps now it will be legally possible to study Hebrew? Why else would there be a dictionary? Perhaps now it’s even possible to go to Israel?”[6]

Many perceived the official Soviet publication of the dictionary as the legalization of the formerly prohibited language. Psychologically it was interpreted as an even broader signal from the regime. One could openly keep the officially published dictionary on the bookshelf. Moreover, it was a good dictionary with a useful grammatical sketch. Even when Hebrew teachers requested works from abroad, they would always ask also for Shapiro’s dictionary even though there were more modern ones there.[7]

Many utilized the official publication of the dictionary in the struggle for recognition of private language teaching as a legitimate enterprise. Legitimization was important for the legal defense of teachers and pupils. It also enabled teachers to announce that they were accepting students and to avoid harassment for “parasitism.”

In 1971 the refuseniks Vladimir Prestin (grandson of the editor of the dictionary, Feliks Shapiro), Sergei Gurvits, Viktor Polskii, and Pavel Abramovich succeeded in obtaining an official permit to teach Hebrew and pay state taxes. In February 1972, however, Abramovich received a notice from the district tax office that he should cease teaching because: “In the Soviet Union, Hebrew is not a recognized language and is not taught in any institution of higher learning.”

Abramovich addressed an inquiry to the Ministry of Higher Education and found out that Hebrew was taught at the Institute of the Peoples of Asia and Africa of Moscow State University, in the Moscow Institute of International Relations, in Leningrad University, and in the Military Institute of Foreign Languages. On this basis Abramovich renewed his request for the recognition of private instruction. The authorities then declared that Abramovich lacked special linguistic training and the appropriate certificate entitling him to teach Hebrew. Even then Abramovich did not give up: he presented a certificate authorizing him to teach issued by the World Hebrew Association. The tax authority, nevertheless, refused to register him. It was clear, however, that the issue was decided not by it but by the KGB.

In 1976 Abramovich tried via the Moscow Information Bureau to announce officially that he was teaching Hebrew. After the bureau refused to accept his notice, he sued them in court and won: the court obligated the office to publish his notice. Abramovich’s apartment was subsequently subject to a search during which all his material in Hebrew was confiscated. The KGB operatives demanded that he completely halt instruction in Hebrew.

Many Hebrew teachers who combined teaching with active Zionist activity were subjected to similar pressure. They were threatened with serious punishment but the regime did not dare to try them for language instruction, preferring to convict them for “parasitism,” “slander,” “hooliganism,” or “possession of drugs” but not for Hebrew teaching. The authorities’ inability to fight openly against language instruction enabled a large number of ulpans to exist on a semi-legal basis. In Moscow alone in 1972 several hundred people were studying Hebrew.

One of the most persistent and stubborn fighters for the legalization of Hebrew and of Jewish culture was Yosif Begun. A man of great personal courage, he decided to attain if not official permission, then legitimacy via silence. Smiling with his kind, fearless eyes (three prison terms did not leave noticeable traces in them), he explained his approach in the following way: “I became a conscious ‘parasite.’ I decided that their arresting me would prove in and of itself that they did not recognize Hebrew teaching as a legal occupation. They didn’t touch me for two years. Every two to three months, I would be called in and a protocol on parasitism would be drawn up but they didn’t take me.”[8] The regime showed its true colors in 1977. Begun was arrested on March 1, Purim day. On that day the first Purimspiel, an amateur Purim play, was supposed to take place in his apartment. The regime was not embarrassed to convict Begun, a Ph.D with twenty-five years of work experience, of parasitism.

The struggle to legalize Hebrew involved not just the tax authorities; letters were sent to Soviet ruling bodies, to the media, and to foreign organizations. In November 1972, Begun wrote his third letter to Pravda in which he pointed out the contradictions between official party policy on the national question and the ban on Hebrew language instruction.

In March 1972, forty-six Minsk Jews protested to the central committees of the CPSU and the Communist Party of Belarus against the refusal of the financial authorities to register them as private Hebrew teachers, terming it a violation of Article 123 of the Soviet Constitution in the form of national discrimination.[9]

In addition to those who combined teaching activity with the struggle for aliya and for legalizing the language, a group of teachers who regarded Hebrew teaching as their basic calling began to form in Moscow. The leader of this group, Moshe Palkhan, had developed a very successful method of instruction and created a school that produced the most prominent Hebrew teachers. “Those teachers constituted a rather interesting group,” recalls Mikhail Chlenov.[10] “At the time many of them did not plan to leave; it wasn’t considered obligatory then. … They taught the activists, who viewed them as some kind of esoteric group possessing some secret knowledge and reading a special literature.”

The second group unquestionably was superior to the first in everything related to the level of knowledge and to language instruction. Understanding their significance for the movement, the members of this group tried to avoid irritating the authorities through blatant participation in other forms of refusenik activity and the latter pretended not to notice their activity.

“Moshe Palkhan was crazy about the language,” confirmed one of his students, Zeev Shakhnovskii, who later became one of the most popular teachers,[11] “and this simply inspired others. Moshe looked at us and spoke in such a way that we understood: well, this is the best language in the world! And our tongues were loosened and we wanted to converse…. He knew how to convey this feeling, this linguistic rapture.”

Moshe Palkhan’s students ─ Leonid Yoffe, Zeev Shakhnovskii, Israel Palkhan, Alexei Levin, Benia Deborin, and Mikhail Goldblat ─ became the best teachers of the aliya group. Yoffe’s students included Dan Roginskii, Boris Ainbinder, and Zeev Zolotarevskii. Fima Kraitman and Lev Gorodetskii studied with Zeev Shakhnovskii; Mikhail Chlenov with Israel Palkhan. Leonid Volvovskii and I studied with Mikhail Goldblat. Many teachers departed but the chain reaction continued until the gates were completely opened in 1990.

Did Moshe have a linguistic education? I asked his younger brother, Israel.[12]

No, in some sense he was a worker; he finished a technical school and served in the army. But Moshe was very capable and purposeful, with a passion for languages. He was extremely competent in Russian, English, and Hebrew. He gradually elaborated his own teaching method and acquired students. Each lesson introduced fifty new words combined in sentences, and each student prepared a story from the new words. Grammar was presented very simply and precisely in subordination to the natural mastering of the language. There was a lot of conversational practice. A person studied five hundred words and already could speak.

Did Karl Malkin study with your brother?

No. He’s one of those who studied independently; there were a few of them.

Who else?

Dekatov, Mikhail Zand.

How did they manage to learn by themselves? Did they have textbooks?

Textbooks, so to speak, were not lying on the streets, but there was Shapiro’s dictionary so that with a strong will it was possible….

Moshe managed to accomplish a great deal. A circle of people in Moscow who spoke Hebrew arose only after him. We would gather at the apartment of Vovulia Shakhnovskii and converse in Hebrew the whole evening.

Shakhnovskii wasn’t religious then?

No. The only religious Hebrew teacher in our circle then was Serezha Gurvits, but he didn’t come to our gatherings. There would be separate meetings with him when he invited us to “kabbalat shabbat” (welcoming the Sabbath). He enlightened us about the Torah.

When did you begin to teach?

After Moshe’s departure.

How many students did you have?

About twenty.

That is, before your time there were individual talents in Moscow….

…and we turned it into a production line.

We met with Moshe Palkhan at his apartment in the Israeli city of Ariel.[13]

How did your interest in Hebrew arise?

It was before my army call-up. My mother was one of the first tourists to visit Israel, having received permission in 1956 to visit her mother there. [14] She returned and said that we ought to leave. I was then studying in school and recall objecting, “What! You want to bring us to that imperialist puppet?” She then gave up on the idea, but she brought back a couple of records from Israel that interested me. The Hebrew music made a strong impression: I heard proud and free people singing. After all, we were living on the outskirts of Moscow, an antisemitic place where I was always fighting with the local boys, who would attack in a mob when we returned from school. … Jewish music helped me understand that the world was not as I perceived it. That is, early on I felt that something wasn’t right: in school there was one world ─ that of the good, beauty, and logic and the other was on the street, in my village…. Only after the army something clicked. At first it seemed to me that abroad was an insane asylum. At some moment I understood that I was looking at the world beyond the Soviet border from inside an insane asylum.

I understand that you began to teach after you received a refusal.

Yes, I was in refusal from1966. Inthis connection there were many unpleasantries ─ my brother was expelled from the institute; my wife was condemned at a workers’ meeting; my father lost his job and so did I…. We had to organize our life anew, and this wasn’t easy in our situation. My mother continued to try to obtain an exit visa, making the rounds of all the government offices, but she received one refusal after another. The last was in May 1967 when it was hinted that never in her life would she see her relatives again. She came home in tears. And then there was the Six-Day War and the entire upheaval.

Where did you get your conversational experience?

I would listen to the radio, sometimes I would meet Israelis, and I made the acquaintance of Professor Mikhail Zand, who spoke Hebrew excellently.

Where did Zand learn his Hebrew?

Independently. He is a scholar, an Orientalist, and met many Israeli Arabs; he was connected to the Institute of Asia and Africa.

Moshe Palkhan left for Israel in March 1971. Although he taught for a relatively short period, he succeeded in instilling his students with such a love of Hebrew that it sufficed for several generations of his followers. After the departure of Moshe Palkhan and Leonid Yoffe, Zeev (Vladimir) Shakhnovskii became the central teacher. A native Muscovite and graduate of the Moscow State University Department of Mechanical Mathematics, he grew up in a family of scientific workers who had also graduated from Moscow University. At first he taught according to Moshe Palkhan’s method and then began to introduce his own elements: a selection of radio broadcasts from Israel and Israeli songs, excerpts from the Torah and Rashi’s commentaries. Together with Benia Deborin he organized the first Moscow “dibur” (in Hebrew “conversation,” it referred to meetings where the conversation was only in Hebrew) for their students. His open and friendly nature attracted people to him. For some time the Sabbath meetings of the best teachers took place at Shakhnovskii’s apartment. As Volodia gradually became more interested in Judaism and began to observe the commandments, he inclined more and more toward Torah teaching. For some time Sasha Ostronov and I perfected our Hebrew with him so that he was also my teacher. Shakhnovskii, who at first was affectionately called Vovulia and then Zeev, taught in Moscow for eighteen years, from 1971 to 1989, and he is still teaching today in Israel.

Tell us about the first ulpans, I asked Shakhnovskii.[15]

The first groups arose even before Palkhan but they basically were not part of future developments. Palkhan was lucky and we with him. He assembled a group that consisted of rather strong fellows. In 1969 Lenia Yoffe and Misha Goldblat began to study with him and they soon began to teach on their own.

How many people were in your group?

Five.

How long did he teach you?

Not long at all. He wrote a booklet “Thirteen Hebrew lessons.” That’s about us; we had thirteen lessons but it was a very strong group.

When did you begin to teach?

In August 1971. That summer Volodia Prestin came to me and said, “They say that you learned Hebrew well?” “Nothing special,” I answer. “We are reading and we are developing….” “What’s the point of reading. I’ll send you five people and you’ll have a group.” Thus my first group was formed in August 1971, which included, incidentally, my best student, Fima Kraitman.

How did you deal with the lack of textbooks and teaching material?

Volodia Prestin handled that. He dropped in on the Lenin Library where he found the textbook Elef Milim ─ two parts ─ and ordered a copy. We made copies of this in our apartments. Misha Zand left us part of his library that had made its way to him after the closing of the Israeli embassy. It included several years of the newspaper for beginners, Shaar lemathil. I distributed it to many teachers and they actively used it in their lessons.

Did each teacher take care of his own supply or was there some coordination of efforts?

I received excellent quality film (negatives) from Volodia Prestin and used it to make textbooks. Other teachers had the same film. Each took care of his pupils.

Ainbinder and Roginskii had telephone channels to Israel. It seems to me that you had one, too, at one time.

People would leave and the links would pass from one person to another. Sara Frenkel, a journalist for a popular Israeli newspaper, used to call me in 1973, particularly during the Yom Kippur War. We would exchange information. At that time the regime began to jam short wave broadcasts that we had been able to hear. She would carefully read out the news in Hebrew; I would record it on a tape recorder and then go over it with my students. This continued until the beginning of 1974 when my telephone was disconnected.

Do you remember the English parliamentarian Grenville Janner? He also called several times. Once the KGB started to jam us during a conversation. He recorded this jamming and then demonstrated this in parliament, raising a commotion about it. After that my telephone was disconnected. And I’m telling you, I heaved a sigh of relief because people had started to call us from schools and kindergartens. Can you imagine, people were calling from the States when it was morning, but in Moscow it was three or four at night.

I understand you well; I went through the same thing. Did they ever reconnect the phone?

No.

Zeev, did foreigners visit you?

Yes, a variety of them, from Europe and America.

What kind of help or support did you request?

In matters related to Hebrew.

Did the organization “Aivrim” from Israel help you?

They sent us books in the mail. In 1973-74 I received around two hundred books just from them.

How did Lena [Shaknovskii’s wife] relate to your activity?

In a business-like manner just like me. After all, she, too, was a teacher. Our pupils and the pupils of our pupils include five Knesset deputies. Solodkina studied with Lena and Sharansky with me. Edelstein studied with my student Gorodetskii. He called me grandfather. Yuri Stern sometimes would come to lessons but I can’t consider him my pupil although he recalled this with gratitude.

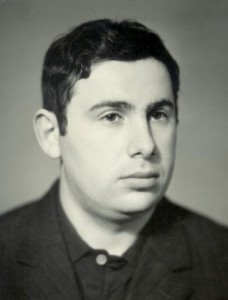

Early elite Hebew teachers l-r: Binyamin Deborin Zeev Shahnovskii, Alexey Levin, Israel Palhan co, Mosow, 1971

In order to take part in the Hebrew-language telephone channels with Israel and other countries, one needed not only a high level of Hebrew and the ability to translate texts quickly but also considerable knowledge about our events. Those who had such channels did not always participate directly in public protests actions. Their basic task was to follow the course of events and, if necessary, quickly and accurately convey information abroad. Boris Ainbinder was one of those people.

Boria, how did you get involved in Zionist activity?[16]

I applied for an exit visa in November 1971 and from that time on, I began to sign group letters. In December 1972, on the first anniversary of the Leningrad Trial, a protest hunger strike was held in several apartments. Polskii, Roginskii, Prestin, Abramovich and I were at Prestin’s home. We fasted for three days. Hunger strikes were also conducted at Slepak’s apartment and elsewhere. That’s how it started.

What channels of communication did you have and in what languages?

I constantly received phone calls from Israel from Sara Frenkel. Michael Sherbourne called from England. I communicated in English and Hebrew.

Who else had channels?

Polskii had a regular channel. Then in 1972 the KGB began to disconnect telephones.

How long did your channel last?

Until my departure.

You were never disconnected?

I was for a short time.

Did you have to convey requests for invitations from Israel or information?

Yes. Polskii would convey the most detailed information and protest letters. I conveyed brief information in Hebrew. There rarely were other people present during my talks.

Were your meetings held regularly?

The most regular meetings were conversations at Polskii’s place. We would gather there once a week. In addition there was the synagogue once a week, holidays, and birthdays.

Some activists were oriented toward the establishment and the Liaison Bureau and others toward non-establishment movements in various countries. How do you explain this?

This is very natural, just as it is in Israel. After all, even if the goal is the same, the methods can vary.

Did foreigners visit you?

Yes, and that was one of my main functions. I dealt rather often with those contacts.

What was the reason for your arrest?

It was December 1972. I think there was a jubilee session of the Supreme Soviet. Many people were detained.

How long were you detained?

Two weeks, in Volokolamsk prison.

Did the KGB bother you on any other pretext?

In connection with Nixon’s visit in May 1972. Then there was a whole story about reserve call-ups.

Dan, did you become a teacher even before you started to study with Lenia Yoffe? I asked one of the elite instructors, Dan Roginskii.[17]

Yes, but I became a genuine teacher after him. Yoffe’s Hebrew was totally conversational and he was a worthy example to follow. Later on, we conversed entirely in Hebrew, which was very inspiring and helpful. One of the elements in the teaching was that in the first lesson all the pupils had to choose Hebrew names and try to speak in Hebrew. As experience showed, this was a very effective method. Paradoxically, here in Israel we began to converse again in Russian.

What memories do you have of life as a refusenik?

I had the good fortune to live at the time of Soviet Jewry’s awakening and to participate in its victory.

In Israel did you participate in the group of teachers that helped Moscow teachers?

Yes, of course. Israel Palkhan arrived in Israel in 1972 and set up an amuta (non-profit organization) called Aivrim. He was the first to understand that one could overcome the postal barrier and make another breach in the Iron Curtain. He used to send books in Hebrew by ordinary mail. Not all arrived but he was persistent. This continued for years and the teachers received many books.

Did you really collect dues and with this money try to purchase and send literature?

At first we collected membership dues but the main source of financing was from contributions. We had to take care of several things: assembling the packages, sending them, and monitoring the delivery. We involved many people in the operation and it worked rather effectively. At some stage, after Israel Palkhan had made his fundamental contribution and left his post, I became president of this amuta.

When was that?

Approximately in 1980.

How much longer did this amuta continue its activity?

Until perestroika, when everything became more or less free. It was a very important activity.

Aivrim, the Organization of Moscow Teachers in Israel

The history of Aivrim is the remarkable story of young Hebrew teachers, ardent devotees of the language, fresh from the struggle to leave and fervently eager to help those who remained behind the Iron Curtain. Upon their arrival in Israel, however, they were told: “It’s good that you came and now your mission is accomplished; settle down and establish yourselves and don’t bother us; we know better than you what needs to be done.”

It’s one thing if, indeed, that had been the case, but, in many instances, the teachers, who had worked directly with Soviet Jews, had a deeper understanding of the situation. In 1973, Israel Palkhan, together with other recently arrived, dedicated teachers, established an organization with the goal of spreading knowledge of Hebrew in the Soviet Union. It was called “The Association for the Dissemination of Hebrew in the Soviet Union,” or in shortened Hebrew form, Aivrim (Aguda leivrit bebrit hamoatsot) and it functioned until the time of perestroika.

Who specifically founded the organization? I asked Israel Palkhan.[18]

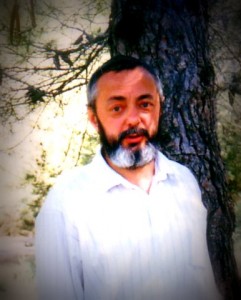

Moscow elite Hebrew teachers l-r fist row: Sergei Gurvits, Leonid Ioffe, Zeev Zolotarevskii; second row: Boris Ainbinder, Dan Roginsky, Israel Palkhan, Natan Libgober, Zeev Shakhnovsky Mikhail Goldblat, Alexei Levin

Yaakov Shkhori, Benia Deborin, and I were registered as the founders. Almost immediately Moshe Palkhan, Karl Malkin, Lenia Yoffe, and Lesha (Aleksandr) Levin joined us. No one helped us ─ neither Yigal Allon, who was then minister of absorption, nor Shimon Peres nor Begin nor Nehemiah Levanon. We had two goals ─ providing people with literature and changing the Israeli establishment’s attitude toward Hebrew instruction in the Soviet Union. And we attained them. First, we ourselves paid dues; each contributed a certain sum. Some people were unemployed and barely making ends meet but they gave money. A considerable number of the books that we sent came from the family of my Israeli relatives. They were books that had remained after peoples finished school, all kinds of old books that weren’t thrown away that we found in attics. A considerable amount arrived after we put a notice in the newspapers. I was invited to speak to pupils at an elementary school in Haifa; I told them about our project, and they also brought their old books.

Among ourselves we divided up the books and the addresses of the Moscow Hebrew teachers whom we knew and sent the material via the mail. In the course of two to three months we sent several dozen packages to Russia. We also used the money we had collected to buy books such as Even-Shoshan’s dictionary. The first round was very successful as the Soviet postal service didn’t manage to react. Some teachers in Moscow thought that the State of Israel was sending them the books. We subsequently became familiar with the American organization Union of Councils for Soviet Jewry, an organization that was headed by Louis Rosenblum, a physicist working for NASA who helped us send the books. He regretted that he couldn’t change Israeli policy, but he did what he could within his organization.

I received Even-Shoshan’s dictionary in the mail!

You see. Before the arrival of our books, Hebrew teachers had practically nothing. This was a breakthrough. After a few months, the Soviet regime started to confiscate our packages. We found out because we sent an inquiry to the postal service about every package that we sent. With regard to some of the inquiries, we were informed that the packages had arrived at the address but for some of them we started to receive the reply: “confiscated.”

Did new people join you during those years?

Yes, the new arrivals ─ Fima Kraitman and Misha Goldblat. When Misha was still in Russia, we designated him as president of our association. When he arrived, he, too, became involved here. Everyone did what he or she could.

Did you succeed at all in changing the Israeli establishment’s approach?

Eventually, but not right away. The turning point came at the time of the Second Brussels Conference in 1976, to which we were not invited. At the time, Alla Rusinek [Levy], who had studied with Moshe in Moscow, was working in the Jewish Agency but the personal connection didn’t help. As we later found out, about eighty refuseniks sent a letter via the Liaison Bureau (Lishkat Hakesher) to the conference’s organizing committee asking it to invite the former refusenik Hebrew teachers now living in Israel to the conference or to establish contact with them ─ the very same Moshe, Malkin, and others. This letter, however, did not reach the conference. Nehemiah Levanon explained to me a couple of years later that his secretary carelessly put it aside. Thus neither we nor the letter made it to the conference. Several months later we nevertheless received this letter via one of the teachers who had arrived in Israel. We indignantly wrote an open letter in which we practically accused the Bureau and the establishment of betrayal. We also informed several dozen Knesset deputies of this disturbing fact.

When the next international congress took place at Binyanei Hauma (Jerusalem’s congress hall), we came with placards to protest. There were only a few of us ─ Valera Krizhak and Yasha Charnyi and Malkin came once. The posters stated that the government of Israel was betraying Hebrew teachers. The American delegates to the conference passed by and tried to explain to us how much they were doing for Soviet Jewry. Some were simply angry at us. In fact, it was Nehemiah who treated us kindly, inviting us in to talk. After we told him everything, he said, “We make mistakes, but you shouldn’t regard us as traitors.” He asked what we wanted and after that, the Bureau’s attitude toward us changed. We told him what we thought ought to be done: supply literature, simple tape recorders, and songs recorded on tape, and send tourists to the Hebrew teachers. We also spoke about more general matters ─ the struggle to legalize Hebrew and the possibility of placing notices in newspapers about accepting students. He said, “With regard to literature, you buy it yourselves and we’ll cover your expenditures.” For several years it worked that way. When we saw that we had achieved our goals, we quietly ceased to exist. We were not drawn to work in the Bureau as we held differing opinions on many issues. We were not very pleased with what they did. The textbook Mori was poor and we were not satisfied with the adapted texts published by the “Aliya” library.

Personal Memories

In my pre-refusenik life I had often visited Moscow but at that time I became familiar only with its museums and theatrical activity. Now I had to adapt to the city as a place for temporary refuge, work, and the aliya struggle. My time was filled by gatherings at the “hill” near the Choral synagogue, farewell parties for those who were leaving, acquaintances, getting familiar with the location and functioning of state institutions, finding work and living accommodations, and the first rounds at the police station.

Like the majority of refuseniks, I expected to receive an exit visa at any time, but it didn’t arrive. At the beginning of 1973, I decided to return to studying Hebrew.

Mastering Hebrew is, of course, not simple ─ another linguistic family, grammatical structure, and lexicon. Knowledge of Russian or other European languages is of little help. In the Soviet Union the process was further complicated by the absence of normal schools for teaching foreign languages. Instruction in Russian schools was based on the assumption that there was no reason for Soviet citizens to mix with foreigners. We were taught basically reading, translation, and comprehension of technical and scientific information. Future Hebrew teachers grew up in this environment. Some, through inertia, taught Hebrew in the same way although, in fact, our needs were essentially different. We needed not only to translate with a dictionary but to live and function in the linguistic milieu, to understand what was said to us, and to be able to express ourselves in the new language.

Moshe Palkhan’s method had the advantages of devoting primary attention to conversation and utilizing several elements for the successful mastery and activation of a conversational lexicon. The lessons also included elements of Hebrew culture and information about Israel in order better to prepare students for life in a new country.

Moshe and his students were inspired teachers. Fanatics for their cause, their burning passion and delight in Hebrew were transmitted to their pupils.

My first teacher, Alesha Levin, a student of Moshe Palkhan, received an exit visa a month after I began studying and he left. His final lesson conveyed the familiar aroma of Jewish joy mixed with some sadness ─ when would we see each other again and would we see each other… The group fell apart and each person had to decide whether to continue studying and with whom. I had additional worries as circumstances had changed for Boris Tsitlenok, who had generously shared his dwelling with me, and I again had to find an apartment.

With the help of a fellow student I found a place in the apartment of Nadezhda Markovna Ulanovskii on the Garden Ring road. Around seventy years old at the time, Nadezhda Markovna changed my disdainful notion about people in the humanities. Her intelligent, hazel eyes radiated light and kindness. She used to organize poetry evenings and well-known bards performed at her place. Most of her many friends, like she herself, had survived the most difficult school of life during the Stalinist period, but they had not demeaned themselves or been broken.[19] She conducted a dissident salon.

I landed in this milieu for the first time and was delighted by the culture of the surrounding people. Once Nadezhda Markovna received an out-of-town guest and she asked me to move to a small dressing room that was used as a workplace concealed from outside eyes and as an additional bedroom. “Don’t feel bad,” she said, smiling, “in this room Solzhenitsyn and Marchenko worked.”

Despite her age, Nadezhda Markovna continued to work, teaching English to advanced students, graduates of linguistic and pedagogical institutes. She didn’t take beginners, as she gently but firmly informed me when I made a request. Once, however, I did her a favor and she agreed to teach me for a trial period, which fortunately I passed successfully. In her unhurried manner, Nadezhda Markovna practically did not touch on grammar but each word was alive and each sentence elegantly suited the situation. She did not like to present separate words, preferring phrases, and she loved role playing ─ how would the student say this phrase on a test? And how would the examiner say it? Each social group has its own sub-language and one has to have a feel for it. She loved to enact various situations: a person feels confident only when he knows how to conduct himself, including linguistically, in a specific situation. Let’s say you’re in an airplane, at a bank, in a café, in the company of friends, or in conversation with the boss…. In explaining the meaning of a word, she frequently demonstrated its meaning by intonation, mimicry, or an expressive gesture and then explained its modulations in various phrases.

After a few lessons she practically ceased using Russian. I would have been happy to study forever with such a teacher but after three months she said that she had nothing more to give me: “From here on life will be your teacher. Read and communicate.”

I must admit that she was the best teacher in my life. She taught me a lot and I successfully used some of her methods later on in teaching Hebrew. For several months I continued to read English books but this activity lost its charm without her participation. I was already able to communicate with foreigners in English.

In the fall of 1973, Nora Kornblum received an exit visa. Formally, her two-room apartment went to me. I promised her that I would accommodate her parents if they wanted to switch apartments; in any case, I wouldn’t need it because I hoped to leave in a year or two. Fate, however, decreed otherwise. An exchange with her parents didn’t work out and during my many years of refusal, this apartment thus became my refuge.

In 1974, I once again renewed my Hebrew lessons. My teacher this time was Misha Goldblat. Lenia Volvovskii and I studied with him. In the beginning of 1975, we ourselves began to teach. In another year and a half, I organized a “dibur” for my students at which we spoke only in Hebrew. After a while the “dibur” turned into a Moscow seminar for Hebrew teachers. I led this seminar for six years but that is a separate story.

In the refusenik community Hebrew teachers often became a focal point of refusenik activity. Their students (and others) would come to them with their problems and questions and they would often be invited to family celebrations. The friendly relations that formed in the ulpans created an atmosphere of trust and mutual support, and in them Jewish holidays were often celebrated together. Those who were just preparing to apply for exit visas also were in contact with the ulpans, which thus served as a bridge between the refuseniks and the remaining Jewish population. The ulpans spread the creative energy of the movement that liberated the Jews from the bonds of fear and ignorance, isolation and solitude, humiliation and despair. The ulpans and circles of Hebrew teachers gave rise to the steadfast fighters for aliya and the rebirth of Jewish national life.

Moscow became the center of the Hebrew renaissance. Through the joint efforts of local and Israeli teachers more effective teaching methods gradually developed and were disseminated throughout the country. When the need for teachers in the capital had been completely satisfied, Muscovites actively began to offer help in organizing ulpans in other cities, as we shall see later.

[1] Kratkaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia, 8:268.

[2] Material from an unpublished manuscript by Izrail Mints, “About Myself,” located in the archive of Lazar Liubarskii.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Vladimir Prestin, interview to the author, January 24, 2004,

[5] Leah Prestina-Shapiro, Slovar’ zapreshchennogo iazyka (Minsk, 2005), p. 7.

[6] Ibid., p. 8.

[7] On February 22, 1972 twenty-two Hebrew teachers appealed to the chairman of the “World Union for the Dissemination of Hebrew” in a letter that described the obstacles facing those who want to study and teach Hebrew in the USSR. They requested that each teacher be sent ten Hebrew-Russian dictionaries, for example Shapiro’s, two large Russian-Hebrew dictionaries, a grammar book and several other books. The signatories included from Moscow: Dan Roginskii, Boruch Ainbinder, Viktor Polskii; Vladimir Prestin, Pavel Abramovich, Pavel Vasilevskii, Sergei Gurvits, Ekhiel Abramson, Israel Palkhan, Vladimir Shakhnovskii, Vladimir Makhlis, Viktor Mandeltsveig, Ida Nudel, Leonid Kelner, and Eli Levin; from Minsk: Arkadii Tseitlin and Ernest Levin; from Tbilisi: Gershon Tsitsuashvili and Shalva Tsitsuashvili; from Leningrad: Mikhail Blikh and David Finkelman: and from Kalingrad: Musia Zaichik. Each signatory included his address. (The letter can be found in Sbornik pisem, petitsii i obrashchenii, no.59 [Centre for the Research of East European Jewry of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem]. [volume, year?]

[8] Yosif Begun, interview to the author, January 16, 2004.

[9] Their letter can be found in the collection of documents Sbornik pisem, petitsii i obrashchenii, no. 63 (Centre for the Research of East European Jewry of theHebrewUniversity,Jerusalem). [year, volume?

[10] Mikhail Chlenov, interview to the author, January 31, 2004.

[11] Zeev Shakhnovskii, interview to the author, February 27, 2006.

[12] Israel Palkhan, interview to the author, July 22, 2004.

[13] Moshe Palkhan, interview with the author, August 7, 2004.

[14] Leah Trakhtman-Palkhan was born in theUkraine in 1913 and immigrated with her family toPalestine in 1922. See earlier in this chapter, p. 000.

[15] Zeev Shakhnovskii, interview to the author, February 27, 2006

[16] Boris Ainbinder, interview to the author, July 4, 2004.

[17] Dan Roginskii, interview to author, August 22, 2004.

[18] Israel Palkhan, interview to the author, July 27, 2004

[19] The memoirs of Nadezhda and her daughter Maya, both of whom experienced Stalinist labor camps, have been published as Istoriia odnoi sem’i (St. Petersburg: INAPRESS, 2003).