Mutual help and support constituted the backbone of the refusenik community. Concern for one’s neighbor and aid to the needy hark back to the most ancient and blessed traditions of the Jewish people. In the Soviet Union, unfortunately, we were not inculcated with those values but our genetic memory and Western help enabled us to overcome that deficiency. On the whole, the refuseniks did not go hungry; they were more or less adequately supplied with clothes and shoes, and in extreme cases they even received Western medicines. For the most part, prisoners of Zion and their relatives also received the necessary support. Whenever someone faced danger, everything possible was done to protect him or her from the regime’s retribution.

The authorities, however, contrived in every way to make the refuseniks’ life more bitter and unhappy, letting them serve as an example of the fate that would befall anyone who dared to oppose the regime. Official propaganda constantly asserted that the activists were paid agents of international Zionism, imperialism, and even of Western intelligence services.

The regime actively exploited Soviet citizens’ complete dependence on the state. For example, when a teacher from Bendery [now part of Moldova] dared to inquire why her dear old friend Yakov Suslenskii had been arrested, she─a Ukrainian woman and mother of two─was fired from her job and blocked from finding a new one. She took her older son out of school so that he could earn some money, but he, too, was turned away everywhere. Reduced to despair after several months, the woman sent a statement to the KGB that she was prepared to sign any testimony against Suslenskii if she could only get her job back. To Suslenskii’s great amazement when he was allowed to look at his file at the conclusion of the investigation, this statement was attached to his case.

While our mutual aid overcame the Soviet citizens’ complete defenselessness vis-à-vis the regime, it nevertheless remained a very complex and dangerous matter that was organized informally. There were many forms of aid, each of which was independent of the other.

First, there were a number of well-to-do people among the Jews of the Caucasus, Western Ukraine, Baltic states and even Kiev and Moscow. When they left the country, several allotted considerable sums for refuseniks whom they knew personally or had heard about on the radio.

Second, local Jews who emigrated were often unable to take with them part of their furniture, personal goods, or everyday items. These were distributed to acquaintances or needy people whom they knew about via ulpans or from the groups around the synagogue. When the mass departure began, at times there were more things to distribute than people who wished to utilize them.

Third, we all received considerable support from Western Jews. Tourists would bring the refuseniks jeans, cameras, electronic goods, and so forth. Refuseniks who spoke Hebrew, English, or French received the most visitors and they would help the others. Many tourists visited ulpans and seminars.

There were always several refuseniks who gathered information about people in need of emergency help. Eventually, lists were compiled of refuseniks around the country; on the basis of those lists, the aid became more organized. A system of personal “guardianship” (“Adopt a family program”) became popular in which an American family, for instance, would take on the care of a refusenik family, corresponding with it and often giving material support. In pairing families, an effort was made to link those that had common professional or family interests. The Americans had considerable experience in such matters.

Another effective method was sending refuseniks checks or monetary transfers that they could exchange at Vneshtorgbank[1] for so called “certificates,” legal foreign currency that could be used to acquire scarce commodities in special “Berezka” stores or could be exchanged profitably for Soviet rubles. Unfortunately this system became obsolete after the Soviets introduced a 30 percent tax on monetary transfers.

Major public organizations in Israel and the West created entire sections that carefully monitored the refuseniks’ situation in various cities and would dispatch tourists in a timely fashion with aid and support. Unfortunately, the coordination among the various Jewish organizations left much to be desired: as everyone wanted to visit the refuseniks who were most well-known in the West, equality in extending aid was not always maintained.

Aryeh Kroll, a kibbutznik, who at one time was secretary of the Union of Religious Kibbutzim, was responsible for working with tourists for the Liaison Bureau (Nativ). He organized youth tourism with the aid of the B’nei Akiva international religious youth organization. Utilizing ties with Jewish and Christian organizations in the US, England, Denmark, Holland, Norway, and Sweden, he sent Israelis with dual citizenship to the Soviet Union. Kroll’s ambassadors were well informed. They brought various items, medicines, and sometimes greetings and letters from relatives and friends in Israel. The Bureau always tried to protect the refuseniks, especially their leaders, from what it viewed as dangerous moves─participation in the democratic movement, excessive political activity, contacts with anti-Soviet organizations in the West, and so forth. Nativ also took care that Western organizations did not entangle the refusenik community in anti-Soviet activity.

At that time, the Liaison Bureau established several entities: in the second half of the 1960s─the Centre for Research and Documentation of East European Jewry at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem; in 1970, the Public Council for Soviet Jewry headed by the rector of Hebrew University, Avraham Harman; and in 1971, the Scientists’ Committee of the Israel Public Council for Soviet Jewry, headed by the renowned physicist, Professor Yuval Neeman. The Public Council dealt with international coordination of the support for Soviet Jewry; the Scientists’ Committee did the same for refusenik scientists. From the middle of the 1970s, the organization of former Moscow Hebrew teachers, Aivrim, began to receive help from the Bureau for aiding Hebrew teachers in Moscow. Jewish organizations around the world took up many of the Bureau’s initiatives.

Committees of concerned scientists, centers for legal aid to refuseniks, and centers for medical aid to refuseniks arose in the U.S., Canada, and other countries. Large organizations appointed coordinators to deal with the dispatch of tourists to the Soviet Union.

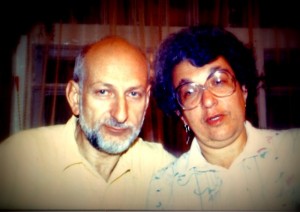

Enid Wurtman, the co-chairman of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews, who was living in Philadelphia at the time, was one of those coordinators. The Union of Councils, a large national organization that was independent of the establishment, created its own programs for supporting refuseniks such as personal “guardianship” of refusenik families or of prisoners of Zion; joint bar or bat-mitzvahs; and a cultural program for sending literature to the USSR. Toward the end of the Soviet era, the Union had fifty branches and 100,000 members in the U.S, making it a powerful force.

When were you co-chairman of the Union of Councils? I asked Enid Wurtman.[2]

After my visit to the Soviet Union, from the end of 1973 until 1977, when my family immigrated to Israel.

Did you deal with tourists for the Union of Councils?

I was responsible for the briefing given to tourists, and I supplied them with the relevant cultural and historical material and refuseniks’ addresses; I gave them material for Hebrew teachers, religious material, and tape recorders. When tourists chose their own itinerary, then I simply asked them to distribute material to refuseniks in cities on their route. In some cases, we proposed to people that they travel to the Soviet Union and we gave them specific addresses. Generally, they were people who knew Israel well and were capable of giving lectures about Hebrew or on religious topics.

With which cities did you work?

Oh, with all of them where tourists could travel: Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Vilna, Riga, Odessa, Kharkov, Tbilisi, etc.

I heard that your own roots are from Odessa.

Yes, my father’s parents, brothers, and sisters were all from Odessa. My father was the only one in his family who was born in America. My mother’s father also came from the Pale of Settlement. Many relatives who remained in Russia perished during World War II. Those losses were enormously painful to us. Had they left in time, they would have remained alive. I couldn’t bear the thought that something terrible might also happen to you. I felt personally responsible for your fate. The pain of earlier losses didn’t let me rest for a minute.

People did work like yours in other organizations, too. Bernie Dishler, for example, was responsible for work with tourists at the Philadelphia Soviet Jewry Council and National Conference.

Yes, he started after we made aliyah. Originally, he was a volunteer in Philadelphia for the Council on Soviet Jewry.

How did you resolve financial issues?

We sought donations, collected money in order to publish material, and sometimes we received help from Israel.

What did you do, Enid, after you made aliyah to Israel?

I joined the Public Council on Soviet Jewry and coordinated the activity of its Scientists’ Committee. In 1971, David Prital, the former secretary-general of the Public Council asked Yuval Neeman to head the Scientists’ Committee. After he consented, the Committee began to function in earnest. Its main task was to involve Israeli scientists in supporting refusenik scientists, establishing contacts among them, and organizing solidarity groups on behalf of those scientists around the world. The Committee published a bulletin that was disseminated around the world, leading to the formation of Concerned Scientists’ Committees in many places.

In the U.S., the Committee of Concerned Scientists began to function in Washington and New York in September1972. Agroup of American scientists, doctors, and engineers decided to undertake actions in defense of their colleagues in the USSR who had been deprived of their fundamental scientific and personal rights as a result of their desire to leave the country. The Committee constantly acquired new members, and it set up branches in various corners of the U.S. and in other countries.

The Soviet Jewry Legal Advocacy Center (SJLAC), which worked jointly with the Union of Councils, was established in 1977 by a group of Boston lawyers. Later it became the Union’s Center for Legal Support, helping it resolve legal issues and also implementing its own projects. The center prepared legal documents related to prisoners’ cases, petitions to international forums, and set up contacts between American lawyers and Soviet refuseniks in need of legal aid.

The establishment organizations had their own centers for legal and medical support. Bernie Dishler coordinated tourism activities for the Philadelphia Soviet Jewry Council in cooperation with the National Conference. He himself visited the Soviet Union in 1975. We met then and ever since that time, we have maintained warm, friendly relations. Like me, he loves to jog and he organized jogging events in support of my family and other refuseniks.

Bernie, what led you to join the Soviet Jewry movement?[3]

I remember participating in the rally in support of Soviet Jews, which took place in Washington prior to Kosygin’s visit to the U.S. in 1971. Later, I met Enid Wurtman, who had returned from a trip to the Soviet Union. That angel touched me with her wing and from then on…. She advised me to “adopt” a refusenik family. We chose Oksana and Aleksandr Chertin, collected money from our friends─five dollars a month─and when tourists traveled there, we sent checks with them. Then my wife Lana and I decided to go to the Soviet Union in December 1975, when we met you. Subsequently, in September 1976, we went to the Second Brussels Conference. Later, in March 1977 when the threat of arrest was hanging over Shcharansky, I went by myself to the Soviet Union. I arrived on the day that the accusations against him were published in Izvestiia. I went to the USSR again in 1983 together with Lana. I am still a member of the National Conference.

To my knowledge, you were responsible in that organization for training and dispatching tourists.

Yes, by 1976 I was already seriously involved in those matters. Regarding tourism as important, we tried to encourage people to travel to the Soviet Union. Later we became wiser and made an effort to send people who had more to offer than just tape recorders and jeans─Jewish pedagogues, lecturers, and so forth. We drew up an appropriate program for which we collected money and we actively promoted our activities. When tourists returned after visiting refuseniks, we used to set up an interview for them in the local newspaper or the national Jewish press, and we ourselves also lectured frequently. We tried to reach synagogues and B’nai Brith groups, offering to organize talks for them, which improved with time. We also obtained photographs and prepared slide shows.

Some people were inspired by such talks and wanted to travel to the USSR with the sole goal of visiting refuseniks. Some ordinary tourists also offered to do something.

When the governor of Pennsylvania planned to travel with a trade mission, he asked us to inform him about the situation of Soviet Jews. We explained things to him, telling him about all that you and others had to undergo and why it was important to raise the issue in front of Soviet officials. We also suggested that he visit some refuseniks. In the future, we took care that the issue of refuseniks was raised during any contacts with Soviet authorities.

Why was it important to your governor?

Because he was a humanist and a good person and also because we were his constituents. He wanted his voters to be satisfied with him. We warned him that the Soviet authorities would try every means of dissuading him from visiting refuseniks but that he had the complete right to do so.

How did you decide whom a given tourist would visit and what he should take with him or her?

It was very difficult to coordinate all this, but we tried to work with everyone who dealt with tourists. We worked with both the Union of Councils and the National Conference. At some point, I became the chairman of the tourism program of the National Conference, that is, I became part of the establishment. We had a special committee for preparing tourists that provided instruction before trips. We tried periodically to bring together instructors from other cities in the U.S. and Canada in order to discuss various issues: what kind of tourists it was preferable to send and to which destinations; what was worthwhile to take along, and for what exigencies they should be prepared. As each city had different practices, such meetings were useful for sharing experience.

Did you send someone to my seminar of Hebrew teachers?

Of course we sent Hebrew teachers to you. I recall that we sent Steven Brown. He went together with our hazan, Cantor Davidson. We also sent rabbis to you. Sometimes a tourist would go to Yuli Kosharovskii and find another tourist there, which was not an optimal situation, but that happened rarely. When someone requested medicine and it was urgent, we would call Pam Cohen and try to find out who was leaving soon. Then, after all, we didn’t have computers and faxes and had to communicate the old way.

Did you coordinate your efforts with Israel?

That was a bit complicated. They sent people all the time but they never shared information with us. The people whom they sent also did not tell us anything. The Israelis wanted to receive information from us and reports about the trips. Information was conveyed in only one direction. They were very…socialist.

Was there coordination with the student group?

We had some links with the Student Struggle via the National Conference; we met with Glenn Richter and Yakov Birnbaum, but there was not much coordination. Sometimes university student leaders were sent to the USSR. In general, we tried to send a variety of people. Once we sent a Catholic nun, Sister Gloria Coleman, who was very active. In the Union of Councils there was greater coordination with students; Enid Wurtman was in charge of that.

How would you evaluate the role of international tourism in the struggle to emigrate from the Soviet Union?

Many hundreds of tourists who arrived in the USSR in coordination with Western independent and establishment organizations and Israel brought hope to the refuseniks. Teachers, musicians, rabbis, cantors, nuns, parliamentary deputies, city mayors and governors, housewives and Jewish public figures brought you a message from the Jewish world. When we all work for a common goal and let everyone do it his or her way, we can accomplish miracles. In this I see the significance of the movement in support of Soviet Jews and its tourist section.

Even with all the varieties of help, life in refusal was complex and difficult. The regime controlled the overseas aid and could halt it at any moment or it could intimidate the recipient and force him or her to reject it. The situation was even more complicated in the provinces, to which foreigners did not always have access. In those areas, monetary transfers from abroad frequently were the sole form of help.

The most difficult task was aiding prisoners of Zion. The main burden, of course, fell on their relatives, who themselves often needed support─and not only materially. One of the most famous activists devoted to the cause of aiding prisoners was Ida Nudel, a woman with a very strong character. Many lovingly called her the mother of the prisoners of Zion.

When did you begin to deal with prisoners? I asked Ida.[4]

In 1972. Some of the prisoners’ relatives began to leave the country and the connections with the outside were broken.

You mean that you got involved because the wives and relatives of some prisoners began to receive exit visas and left?

No, that’s not it. I would say rather that it’s my nature. I began to take an interest in the matter and decided I had to do it.

Dealing with prisoners of Zion was a difficult matter: correspondence with the authorities and with the prisoners themselves; one needed to know how to maintain relations with family and to prepare and send packages to the camps….

I dealt with everything but I did not have the right to send packages. I would give everything to the relatives. I was living in Moscow; the relatives stopped by my place on their way to the camps or prisons and received whatever I had been able to collect.

Did you have a connection with any Western organization?

I had a link to a French group.

What about Michael Sherbourne in England? After all, he knows Russian.

While I had a telephone, there was a link. I myself led a semi-underground way of life and hardly associated with anyone because I knew that the Jewish circles were very talkative. It was necessary to be very cautious in dealing with information; people took a risk. People who were released from camps would come and bring information, which sometimes they had concealed in their anal passage.

Did you have helpers?

Yes, Arik Rakhlenko and Boria Tsitlenok. They would travel to the places of incarceration, accompany relatives to meetings, and so forth.

All information about prisoners was sent to me. Moreover, every prisoner knew my address. I would write to them, send birthday greetings, collect signatures in their defense near the synagogue, and go to the Interior Ministry in connection with their cases. When I came to the head of the division in the Ministry, he would get up and shake my hand. I used to explain to him frankly my relationship to those people and why I was concerned. Once, even the head doctor of Gulag decided to make my acquaintance. He then taught me how letters should be written and whom to intimidate and how. He was not a Jew; he simply was a human being.

How did you explain things to them?

I didn’t hide anything or lie to anyone; I explained everything openly and frankly. I always had the USSR Constitution in my bag and I spoke only in terms of the paragraphs of the constitution. They had difficulty arguing with me. Then I would tell the activists how I managed to get people out of the penalty isolation cell or to provide a doctor for a sick person and then persuaded him not to send the sick prisoner to hard labor. I sat and worked day and night. Thanks to that, I survived in refusal. I am simply the kind of person who needs something to keep herself busy. In addition, I worked because the KGB continually threatened to arrest me as a parasite.

How did you locate prisoners and their relatives?

My sister sent me addresses from Israel. The newspapers published the addresses and names; she would write them down and send them to me. Arik Rakhlenko went to the Interior Ministry and clarified where people were serving time, in which republic. Most frequently I used to go to the synagogue and question people. I had extensive ties with other cities until my telephone was disconnected. Do you remember Markman?

Yes, he was my friend from Sverdlovsk; he was arrested in 1972.

I knew his wife Greta very well. She lived at my place.

Did you manage that case?

I went with Greta to the Supreme Soviet. I remember that five people from Kishinev and Volodia Slepak were with us. I was in close contact with the Zalmansons’ father, and in touch with the democratic dissidents, in particular with Nina Ivanovna Bukovskaia. They didn’t give up and stuck to their business.

There were problems?

And how… this was a society deep in pain and suffering. There were women who were afraid to associate with me, women who were afraid that I wanted to take their husbands away. There were all kinds…. There were some who didn’t want help, but I didn’t know that. They concealed the fact that they were Jews and were leaving. There even were mothers who had their own children arrested so that they wouldn’t leave, but they regretted it later. When the KGB began to conscript seventeen to eighteen year olds into the army, there arose a kind of protest movement. Those boys hid in my place.

You had a one-room apartment. Where could anyone hide there?

I had one room and a kitchen. There was a little sofa in the kitchen on which everyone slept─the prisoners who were released from camps, the army lads, and everyone.

To my knowledge, Dina Beilina dealt with some prisoners [skipped line] and took care of some people until the trial.

I don’t know whom she helped. When I got into this, Volodia Prestin explained to me that I must regard each person as a potential co-defendant because we probably all would be arrested. “You see,” he told me, “this is a dangerous matter.” And I followed that advice. Dina didn’t tell me anything about her life and I didn’t tell her anything about mine because our lives were not normal.

In 1977 you organized a women’s group and you initiated a series of demonstrations.

I chose six women who had a chance of not landing in prison and who agreed not to tell anyone what we would do: Natasha Khasina, Galia Nizhnikova, and others.

How did you know that they wouldn’t be arrested?

Khasina had a small child and the others also had certain extenuating circumstances. In my case the chance was fifty-fifty, but at that time, I had already become well known.

How many demonstrations did you manage to hold before you were arrested?

Six.

When you were in exile, did you correspond with other prisoners or was that impossible?

I was busy with my own survival there; I wrote letters, but it wasn’t the same thing. Correspondence among prisoners was prohibited, which made it very difficult. I received a few letters from Tolia Altman and something from Zalmanson. I worked and therefore I had considerably less time and energy.

What work did you do?

I was a guard. I had a dog and we worked together.

Without a weapon?

Yes. Prisoners are not allowed to have arms.

Were you helped by people at liberty?

Of course. People came endlessly; Lvovskii came, Tsirlin, and others.

I heard that it was hard for you in exile.

It was very hard─a person who has spent all her life in Moscow winds up in a Siberian village. The temperature was minus 40 to 50 degrees centigrade. I needed wood for the stove. There were no food products; in the summer I had to raise everything myself. There was no water in the hut and it was very hard to carry the water bucket. I would have to drag it back and forth all day. If you are a man, you can arrange something, but if you are a woman, everyone is afraid of you and no one will help.

Did you make any acquaintances there?

What kind of acquaintances in the depths of Siberia?! Do you know who lives there? They take an intelligent person and drop her into an environment where every second word is a swear word. When they talk to you, you have to sift out the swearing and put together the sentences. It’s an entirely different milieu and it’s exile. You are in complete isolation and no one will help you. They write articles about you in the papers. There were no local papers but there was a Tomsk newspaper. We were200 kilometersnorth of Tomsk. It’s not the tundra, but it’s already the deep north, with about ten farmsteads. I had a room in a barrack where men who had been released from prison were living because they were not allowed to live in the city. I was the only woman. In their eyes, I was the man in the moon. There was no stove in my room. The building was heated by a boiler room with the help of batteries but when it was minus fifty, everything froze and it was very difficult.

I organized a protest because of the rats in the building and, as an exception, I was permitted to purchase a little house. In principle, an exile can rent lodging, but no one agreed to rent to me. I bought a small one-room house that had a stove but I didn’t know how to use it. No one showed me how and I almost died there a few times. Finally, the police chief showed me. When he found out who I was, he would summon me, lock the room, and we would converse for hours. If he forgot to lock the door and some policeman entered, he would say to him, “Leave, I’m busy now.” He was a person with a strong legal education; he was forced into the deep backwoods.

When you finished your exile, you weren’t given a residence permit for Moscow?

No one was given that.

After you settled down in Bendery, did you continue to correspond with prisoners?

Of course I did. People got out and left the country. Life continued. The Royaks and Libermans were refuseniks there. They received me very nicely. But the police… simply threw me off the bus whenever I would try to leave town. They grabbed me by the arms and legs and tossed me off.

It was another long five years after her release before Ida Nudel received an exit visa. In March 1987, she was flown out on the private plane of the well-known businessman Armand Hammer. Five thousand people gathered at Ben Gurion airport to welcome Ida upon her arrival.

Along with Ida Nudel, Dina Beilina did much to help refuseniks and prisoners of Zion. An active person with clear leadership abilities, she dealt with many issues: for several years she was the academic secretary of Aleksandr Lerner’s seminar; she took part in the preparation of analytic surveys for Israel; she participated in meetings with important Western public and political figures; and she maintained contacts with aliya activists from many cities. For several years, Dina was in charge of preparing and compiling lists of refuseniks, including those lists that later figured as part of the espionage charge against Shcharansky.

After Shcharansky’s arrest, Dina declared to Western correspondents that she was the one who dealt with the lists and Shcharansky had nothing to do with it. Under those conditions, that was a courageous act with unpredictable consequences. Incidentally, to this day, Dina is confident that there was nothing secret in those lists.

Ida Nudel dealt basically with those who had already been imprisoned. Beilina got involved when an activist was threatened by arrest or a file was opened against him or her. She often had to prepare material to send to the West about legal trials. Some notes remain and she also remembers many interesting details that were characteristic of that time.

What cases did you deal with? I asked Dina.[5]

So many that I can’t remember them all. I was, indeed, in close touch with activists from several cities and dealt with various kinds of aid to refuseniks. People whom the KGB had begun to harass frequently approached me. Do you remember the arrest of Mark Nashpits and Boria Tsitlenok? They were taken away at the final demonstration of the Hunveibins, as some people called them, which took place near the Lenin Library at the end of February 1975. The demonstrators managed to stand with their posters for less than a minute, after which all of them, except Sasha Gvinter, were dragged into the library building and then brought to a detoxifier (drunk tank). Nashpits and Tsitlenok were declared the organizers and put on trial. The others were sentenced to fifteen days in jail.

When it became clear that Nashpits and Tsitlenok might receive a long sentence, a struggle began for their release. Three days later, a group of twelve activists, including Slepak, Lunts, Prestin, Goldfarb, Davidov, and others went to the prosecutor’s office to protest against the arrest. Five of them were received by General Tsybulnik, who didn’t say anything intelligible. A statement signed by a large number of refuseniks was composed and then sent to the West.

Debora Samoilovich played a successful role in this case. A professor at the Kurchatov Institute, she appeared at the judicial session in an elegant cloak decorated with medals and awards. It was quite a sight! An imposing, beautiful woman, who looked like an important public figure, she presented herself to the guard as Tsitlenok’s aunt, and she was allowed inside. Possessing a unique memory, she was later able to recount everything that went on behind the closed doors.

I presented myself as Nashpits’ aunt, but they “figured me out” and didn’t let me in. Nashpits received five years of exile and Tsitlenok four. The appeal didn’t change anything. The fellows then were not heard from for several months; the regime, evidently, decided to recoup its losses on them during the transport. We carried on the struggle during each day of the transport until they showed up─one in Eniseisk and the other in the Chita Region. We then traveled to their place of exile. The first time I went with Musia, Nashpits’ aunt, in order to help him get set up and the second time with Yosif [Dina’s husband]. Tolia Shcharansky, Aleksandr Lunts, and other activists went to visit them.

What other cases did you deal with?

Leva Roitburd, one of the well-known Odessa activists, tried to travel to Moscow to meet with some American senators in June 1975. The local KGB warned Leva that he would have to pay for it if he tried to leave Odessa. Not long before that, a threatening article featuring Roitburd appeared in the local paper Vechernaia Odessa. Despite the threats, Leva decided to go. He was arrested at the airport for allegedly resisting the police. Misha Liberman and I flew down for the trial. We managed to record the testimony of the witnesses, including the chief navigator of the local steamship company, an important person by Odessa standards. He stated directly that he saw how Leva was pinned down and taken away without any cause or explanations, and that Leva didn’t raise a hand against anyone. To this day, I don’t understand how this person was allowed to appear at the trial!

We immediately transmitted the lawyer’s speech and the witnesses’ testimony by telephone to the West. We needed to show our friends that this was a provocation. In those years, the regime usually portrayed the arrests of activists as part of the struggle against criminals. After all, in the West, too, people attack police. The case, however, was concocted very clumsily. Evidently, the local KGB did not expect our intervention or such a speedy reaction. It was on the eve of the signing of the Final Act in Helsinki, and at a preparatory meeting, the Soviet delegates were asked how the protection of human rights in the USSR was in keeping with the arrest of Leva Roitburd for his desire to immigrate to Israel. Leva was threatened with up to five years in prison. Without an explanation, the sentencing was put off for a week. Leva received two years, which in those conditions even represented a victory.

Were there other such victories?

The most impressive in that sense was the case of Boria Chernobylskii and Yosif Ahss. They were both released before the trial although they had faced the threat of a serious charge. In my opinion, that was the sole such case in the Soviet Union.

The events unfolded in September-October 1976. It was a hot time. On the one hand, the refusenik symposium on culture was gathering steam and on the other, the Helsinki group had been working for several months (since May 12). The authorities were nervous and, seemingly, somewhat confused.

At that time, twelve activists, including Slepak, Chernobylskii, Ahss, and others began a protest campaign against unjustified refusals. They wrote a letter demanding that OVIR provide written replies indicating the reasons for a refusal and its time span; they also demanded the right to submit an appeal and be present during its consideration.

On September 19, the letter was brought to the reception room of the Supreme Soviet and, in accordance with the law, the petitioners waited a month for a reply, but none arrived. The activists then organized a series of demonstrations that began on the day following Simhat Torah and continued on October 17, 18, 19, and22 inthe Supreme Soviet building, October20 inthe Interior Ministry building, and on October25 inthe reception room of the CPSU Central Committee.

The number of participants grew daily. I don’t remember whether I participated on the first day, but I came on October 18th, when about twenty of us demonstrated with yellow stars sewn onto our clothing. At the end of the day, we were taken to a forest about fifty kilometers away and some of us were seriously beaten. Shcharansky arranged a press conference afterwards.

On the following day, about fifty people arrived at the Supreme Soviet. We demanded a reply to our letter and punishment for those responsible for the beatings. At the end of the day, we were promised that Nikolai Shchelokov, head of the Interior Ministry, would receive us on the following day. He received a delegation of three people.

Do you remember who was in the delegation? I asked Dina Beilina.[6]

According to the notes that I made soon after those events, the three were Slepak, Chernobylskii, and Shcharansky. A total of 52 people with yellow stars on their clothing went to the Interior Ministry. Shchelokov declared that he was not responsible for the security of the refuseniks. At the end of the day, the demonstrators were again transported to the forest, but this time they were not beaten. Four of them─Viktor Elistratov, Mikhail Kremen, Boris Chernobylskii, and Arkadii Polishchuk were separated from the others and detained.

On October 22, the refuseniks returned to the Supreme Soviet, after which over forty people with yellow stars on their chests, encircled by the police, moved toward the Central Committee reception hall. Yosif Ahss, Yosif Beilin, Vladimir Slepak, and Anatolii Shcharansky were received by Albert Ivanov, the director of the Central Committee’s department of administrative organs. We did not receive information about the four who had been detained. Toward evening, the demonstrators were brought to a detoxifier, where a protocol was drawn up, but they were not arrested. At that time, it became known that Chernobylskii was in the Butyrka prison and that Elistratov, Polishchuk, and Kremen had each received fifteen days in jail.

On October 25, thirty-eight people again set out for the Central Committee. Seventeen were arrested on their way, including Yosif Beilin, Aron Gurevich, Aleksandr Gvinter, Ilia Zelenyi (from Odessa), Yakov Rakhlenko, Vladimir Slepak, Yulii Kosharovskii, Zakhar Tesker, Igor Tufeld, Leonid Tsypin, Vladimir Shakhnovskii, Leonid Shabashov, Anatolii Shcharansky, Dmitrii Shchiglik, Isaak Elkind, Evgenii Yakir, and Leonid Volvovskii. Feliks Kandel was arrested near his home. They all were sentenced to fifteen days.

Six women were fined 25 rubles each and released. Yosif Ahss was arrested at home and placed in the Butyrka prison. He and Chernobylskii were charged with hooliganism. You, if I recall, were sent to Serpukhov, a branch of Butyrka, and your wife and I went to see you.

When it became clear that Chernobylskii and Ahss could be sentenced to lengthy terms, I turned to Sofia Vasilevna Kalistratova (a well-known Moscow lawyer who defended many democratic dissidents), and we had the idea of forming an “assistance group to the investigation.”

The assistance group was formed quickly on November 1, 1976. It included activists from the Jewish movement and observers from the Moscow Helsinki group; Kalistratova became the consultant on legal issues.

Dina, how did this group operate?

Sofia Vasilevna was the chairperson of the group and also played the role of judge. We summoned witnesses─not everyone had been sentenced to fifteen days. I was the secretary and wrote a genuine protocol. The jurors were professors Meiman, Brailovskii, Lerner, and some other professors and refuseniks who were well known in the West. Sofia Vasilevna posed questions to each witness. It soon became clear that Chernobylskii and Ahss had not struck the policemen; rather, the police had beaten them.

Yes, we were transported a distance of about fifty kilometers, dropped in a forest, and the policemen began to push us away from the cars in order to leave, but we demanded that they bring us back to where they had picked us up. It was already rather cold. One of us lay down under the wheels. The policemen acted roughly, beat us, and cursed. They broke Tesker’s nose.

We brought the document, which we called “The account of the assistance group to the investigation,” to the prosecutor’s office and also transmitted it to the West. Near the synagogue, we handed out two pictures to all the foreign tourists─one of Ahss’ wife with his two small daughters and the other of Chernobylskii’s wife with his two little girls. The photographs were extremely touching. Boria and Yosif sat in prison for less than a month but it was the real thing─they even shaved their heads! They were released before the trial under the formulation that they “do not constitute a danger to society.”

Chernobylskii appeared at my place at night immediately after his release, finding it hard to believe that he had been freed. After all, the case fell under the article “resisting the authorities,” for which one could receive three years or even more.

Didn’t you also gather urgent information from “hot spots”?

Yes. My first experience was the case of Aleksandr (Sasha) Feldman. Yosif [Dina’s husband] traveled to Kiev after Sasha’s arrest, thoroughly investigated the scene of the occurrence, and talked with witnesses. He brought back important information.

After Shcharansky’s arrest, Volodia Kislik appeared to be under the threat of arrest. He had transmitted two articles to the West: one about nuclear physics that contained absolutely open information and the second about the regime’s emigration policy. They were confiscated from a tourist to whom he had entrusted the articles. In May 1977, Kislik was mentioned in an article in Izvestiia about this tourist but the main attack against him began in the fall in several Kiev newspaper articles. Most importantly, an item in Pravda Ukrainy that appeared just before the Babi Yar memorial day, claimed that Kislik had transmitted secret material to the West. His place was searched and a file was opened against him; he was subsequently summoned to interrogations with regard to his own and Shcharansky’s case. Many interrogations followed. At that time, the New York State attorney-general arrived in Moscow for a visit─an opportunity that couldn’t be missed. At my request, Zhenia Tsirlin flew to Kiev and back for this newspaper article. In Kiev, he did not go directly to Kislik so as not to “stick out” but to his refusenik colleagues, Kievans from the technical physics institute. In the morning, this article was translated into English for the New York attorney-general, who was told that the article contained a patent threat to arrest Kislik. In addition, the New York Times correspondent, Craig Whitney, traveled to Kiev. At the beginning of December, Whitney had published a large article about Volodia. I don’t know why Volodia was not arrested back then─because of that article or for some other reason.

Dina, were you also involved in the trial of the Zavurov brothers?

Yes. They were metal engravers from Dushanbe [the capital of Tajikistan]. They have been in Israel for a long time now and successfully continue to practice their profession. They applied for exit visas in 1975 and already had them in their hands, but for reasons beyond their control, they delayed their departure by one day. It seemed like nothing terrible, the customs didn’t check them because they attended to some foreign delegation out of turn, but the brothers’ visas were taken away. Amner and Amnon then refused to take back their passports. They were active fellows who continued to fight, including via Moscow.

On November 16 they were arrested for fifteen days in Shakhriziab, in Uzbekistan. During a stroll, Amner escaped from preliminary detention and made his way to his parents in Dushanbe. Amnon was released after a day but a criminal charge was brought against Amner, who was arrested in Dushanbe and again brought to Shakhriziab. The trial was set for December 26. At the brothers’ request, we sent a lawyer from Moscow, who reported that the session would be conducted in the Uzbek language. He asked for our help with a translator because it was hard to find one locally─evidently, people were afraid. I proposed that Lipavskii go to help. He had lived in Tashkent for several years and knew the language well. Lipavskii agreed, but in the end he did not go there; he said that he had been unable to fly, apparently because of KGB interference. In parallel, I also asked Leva Gendin whether he could unobtrusively bring the trial material to Moscow, which he managed to do, flying there and back. It was strange that Gendin did not see Lipavskii at the airport.

At the trial, the lawyer convincingly demonstrated Amner’s innocence; the defense witnesses spoke well; and friends in the West began a campaign. The judge nevertheless sentenced Amner to three years of labor camp, in essence because he refused to take back his Soviet passport.

What happened subsequently was the most interesting part, perhaps throwing light on this whole strange story. After Shcharansky’s arrest, Boris, the father of the Zavurov brothers, was summoned to the KGB; they suggested that he sign an article similar to Lipavskii’s [in Izvestiia accusing Shcharansky of spying for the West] and also testify that Joe Pressel, the first secretary in the American Embassy, had traveled to Tajikistan in order to gather secret information about military bases around Dushanbe. “If you agree, we’ll free your son Amner; if you refuse, we’ll arrest your second son Amnon.” That was the choice. Joe Pressel truly had traveled in those areas. Shcharansky gave him the addresses of people who were not afraid to meet with him, and the Zavurov brothers were on the list. They showed Pressel the local attractions and let him sample the wonders of the national cuisine. When the regime began to elaborate their version of Shcharansky’s espionage, Pressel, according to the scenario, was assigned the role of the CIA resident, and the KGB decided to utilize his trip to the south to render the espionage story more convincing.

To Boris Zavurov’s credit, it should be noted that he rejected the KGB’s proposal. Amnon then traveled to Moscow and told us the whole story, which we then conveyed to the West. The Zavurov trial helped me, in conjunction with other facts, to expose Lipavskii. In September 1976, about sixty gravestones at a Jewish cemetery near Moscow were vandalized. I asked Misha Kremen to photograph the cemetery and Lipavskii was supposed to bring me the photos. Lipavskii, however, delayed and in two weeks the mess had been removed and flowers planted at the cemetery. I understood too late who Lipavskii really was, and the activists to whom I related my suspicions, including Shcharansky, Lerner, and Slepak, didn’t believe me then.

Dina, you were, of course, also involved in Shcharansky’s case….

That, as you understand, was the most serious case that I encountered, not only because I myself was a part of it. At first, there was a very complex situation in connection with him. I heard from several refuseniks─we won’t name them now─that Shcharansky was a dissident and this espionage case shouldn’t be allowed to weigh down the aliya cause. From Israel they demanded that I stop defending Tolia if I ever wanted to receive a visa to Israel. This was at a time when the situation was already very tense. On the first Sabbath after that terrible article in Izvestiia in which the aliya activists were accused of treason and espionage, only a few refuseniks, surrounded by a crowd of KGB agents, appeared near the synagogue. People were afraid. In the first three months after Shcharansky’s arrest, no one was summoned for interrogations, information was lacking, and it was very difficult to explain to our friends in the West what was happening.

What did you do during those months?

It was important at that time to show that Shcharansky was one of ours, a Jewish activist, that he had been arrested and charged with doing what we were doing together with him and sometimes even without him. If Tolia had been defended only by his relatives, and the Jewish activists had remained on the sidelines, it would have been very difficult to muster public opinion in the West. After all, the family defends its own in any situation.

What happened when the interrogations started?

They began after three months. I helped the inexperienced refuseniks overcome their fear of interrogations at Lefortovo prison. I collected and analyzed information from the interrogations, forwarded to the West letters and appeals in his defense, and sometimes composed them myself. I collected evidence of procedural violations and demonstrated the impossibility of an objective defense by Soviet lawyers; together with Tolia’s mother, we met with Western lawyers, and I accompanied her everywhere. At someone’s interrogation, it was said that a center of resistance to the investigation was operating in Moscow.

Many people, as they left an interrogation, would hastily record everything that they remembered and would bring it to me, saying, “transmit it to the West; I want them to know the truth about what is going on and to know that I wasn’t broken.” People who had never been interrogated previously behaved courageously. For example, Alik Kogan, a quiet mathematician, was dragged out of his bed to an interrogation early in the morning. He was presented with twelve of our collective letters that “inclined” [to charges] under Article 190. The interrogators said that they knew that he had not signed anything, that Shcharansky had done it for him. He was threatened that if he remained silent, he would be arrested. And Alik, in front of the astonished investigators, signed all twelve documents. Leva Ulanovskii was threatened with arrest, but in reply he demanded that they conduct the interrogation in his native language, Hebrew, and he insisted on it. My husband Yosif reduced the interrogation to a dispute about recording a sentence in the protocol that he was an Israeli citizen.

It was much more difficult in other cities, but there, too, witnesses acted in a worthy fashion. Lev Ovsishcher in Minsk, for example, declared that he considered that the Shcharansky case was fabricated. At the time of the trial, I had accumulated dozens of copies of interrogations.

What can you add about the material aid to the refuseniks and prisoners of Zion?

In addition to the Georgian millionaires who helped us, we were also left money by people from Lvov, Kiev, and Moscow. They left rubles, which was entirely “kosher.” Israel helped with money to pay for visas. That aid arrived via the Dutch embassy. We also helped the relatives of prisoners of Zion with money for lawyers, trips, and food parcels. There were many expenses. We were not acquainted with the majority of the relatives; it was rather dangerous to be in touch with some of them.

Did you also help prisoners?

Yes, I handled the cases that came to me. Ida dealt with those who had been imprisoned earlier. She carried on an extensive correspondence with people in prisons and labor camps, transmitted information to the West about the condition of prisoners, and supported their families.

I had my contacts in various cities, and people also came to me. Sender Levinzon from Bendery was arrested in May 1975 on a fabricated charge of speculation. He is the brother of Klara Suslenskaia. Go prove that he was arrested because of his Zionism! He received a seven-year sentence. Showing that activists were arrested because of Zionism was a large part of our work.

Did anyone help you?

Various people helped, depending on what needed to be done. No one refused. Arik Rakhlenko, Misha Kremen, Gena Khasin, Boria Chernobylskii, and others. Shcharansky was continually dealing with those matters. Press conferences were held at Lerner’s or Slepak’s place. I was helped by lawyers, most often by Kalistratova.

Did she act out of altruism?

Amazingly so. She called herself “the Russian national minority among the Jews.” She was a member of the Helsinki group. There was another lawyer, Zolotukhin, and Reznikova also helped.

From time to time women’s mutual help groups were formed, for example that of Ira Gildengorn.

Women’s groups became active after Shcharansky’s imprisonment. I asked them not to go out to demonstrate before his trial, thinking that it was preferable not to divert attention from the trial, but others thought differently. My attitude toward the women’s groups, therefore, was ambiguous. For example, I went with the women to the Central Committee but not to street demonstrations. I recall that Larisa Vilenskaia offered to chain herself in some public location. I said to her, “It’s not necessary before the trial.” After Ida Nudel and Volodia Slepak were taken, the women quieted down somewhat; they then went out again, but after the trial. It was a terrible time but the young women were terrific and didn’t give up.

How were you in contact with other cities?

There were several channels of communication. The religious had their own, which was divided up into the various streams; the Hebrew teachers had their own; the seminars had theirs; and we had ours. Sometimes, however, especially in small cities, the same people dealt with various matters.

Did you also deal with the organization of aid to other cities?

Yes. In the provinces, Jews who had already submitted applications for exit visas were completely exposed, and after their dismissal from work, they couldn’t find even low-paying work. Via local activists we located the needy refuseniks and we sent the lists to the West. The requested items were brought in and we had to find a way of delivering them.

It’s interesting that during a search before Tolia’s arrest, the KGB agents pounced on my two savings books, but it was written there that the money had been bequeathed by my father in 1956. They were terribly disappointed; apparently they had hoped to cook up something but it didn’t work out. Money didn’t figure in Shcharansky’s trial and this would have added a little color.

How did you manage with medicine?

Foreigners brought them at our request. If something could be obtained in the Soviet Union, it was taken care of locally. In this matter we were aided by sympathetic doctors who had not applied for visas. We also received help in obtaining food parcels and delivering them to prisoners. There were sympathetic store managers.

With which activists and foreign organizations did you work?

Sometimes I knew on behalf of which organization the tourists came but not always. Now I realize that activists were continually arriving from “The 35’s” in London, from the group “Fifteen” in Paris, from Genia Intrator in Canada, and from Irene Manikovsky of the Union of Councils. I became acquainted, for example, with Enid and Stuart Wurtman without knowing from which organization they came. Then it was not the main thing. I was barely in contact with the Liaison Bureau and the organizations linked to it. The Bureau wasn’t pleased with us because they thought we were too active and because we circumvented them, directly contacting other organizations.

After your departure and Ida’s arrest, Natasha Khasina dealt with organizing aid?

Yes. When I was already in Israel, she also sent me information about arrests and professionally prepared legal material, which I then disseminated as widely as possible. She managed the cases of Edelstein, Kholmianskii, Elbert, and many others. She helped Shcharansky’s mother.

In Israel did you continue to deal with prisoners’ affairs?

Of course, for nine years. The Bureau paid for my phone conversations with Moscow. I continued to deal with them until Shcharansky’s release and the arrival of the veteran refuseniks and Natasha Khasina. Then I decided that I had had enough.

Natasha Khasina dealt with prisoners of Zion from 1978 to 1987, for nine years. She is a remarkable person. She never knew her father, who was arrested before she was born. She grew up in the far north, near Vorkuta. An athletic individual, she is strong-willed and fearless. She was very familiar with life in the harsh locations that often became the place of exile or imprisonment of Jewish activists.

“I know,” she recalled, “what it’s like to walk around town at minus 40 degrees centigrade with an empty bucket in search of a non-frozen well and then to wait in a long line because everyone streamed to where there was water. I know what it’s like to chop wood or stoke a stove, and other “joys” of life under those conditions.”[7] After her arrival in Moscow, she succeeded in passing the entrance exams to the technical physics faculty at Moscow State University (MGU) and went on to complete her degree. Natasha always had a responsible attitude toward her work, carefully analyzed the situation, and often proposed serious solutions. We worked side by side for several particularly difficult years. The reward was friendship with her remarkable family and mutual respect.

My first question to Natasha was: Did you help prisoners because you understood their difficulties so well?

Not really. Remember what happened in 1978: Ida Nudel was exiled and Slepak was serving time. Ida was not detained before the trial so that she was able calmly to leave lists and addresses and to explain where the money and suitable food products were located and what to do so that the prisoners were not left hanging in the air.

Around that time you were already in refusal for two years. Did you do something else in those years?

Once Dina asked me to retype some thoroughly worn out lists of refuseniks and to insert various additions─those who gathered near the synagogue and near OVIR. Those were the same lists that lay at the basis of the charge against Shcharansky. When the raids began and they came after me and Dina and everyone else, I brought the lists to my friend. Then Dina dropped in there, apparently, with her “tails.” She asked to remove the lists from there because the apartment had been exposed. In addition to the lists, there was a whole pile of literature there that Shcharansky had received. I brought everything to an address that Tolia had given me. It was some friend of his and Ida’s who lived in the building of the Higher Party School. Do you know what I did? I gave those people a portfolio or little suitcase; they didn’t know what was there, and I said, “In case anything happens, this is mine.” After Dina’s departure, it became totally my responsibility to manage the lists.

How did you get involved in the work with prisoners?

Ida left me all the information and asked me to write to the prisoners. I informed them that Ida had been arrested and if they had any requests, they should write to me. In Riga I became acquainted with the parents of the Zalmansons and of Mendelevich and gradually met the parents of other prisoners.

How many prisoners of Zion were there in your time?

The number fluctuated between fifteen and twenty. Some would get out and others were arrested. It seemed that the KGB saw to it that the level was kept within certain limits.

How many people helped you with your work?

A few─about five to seven. Many people helped the Shcharanskys with all kinds of baked goods. Raia Shcharansky, Tolia’s sister-in-law, learned how to bake high-calorie cakes with vitamins that outwardly resembled oat cakes. The originals were removed from the packaging and hers were placed there instead. Lev Blitshtein and Tsirlin helped. Blitshtein said to me, “As long as we have your head and my connections, there is nothing to fear.”

What did he mean by connections?

He organized food products and other things. We were afraid that one of our people would foolishly blab somewhere. Therefore, aside from Blitshtein and you on occasion, no one knew anything. Even my husband didn’t know anything.

Who accompanied the relatives to meetings?

Zhenia Tsirlin, Volodia Magarik, and Lenia Tesmenitskii.

In Leningrad did Taratuta help prisoners?

Yes. When Zelichenok and Lifshits were imprisoned, their wives appeared in Moscow but others were supported locally.

Did the women’s group help with the prisoners?

No. We met for another purpose. It was Ida’s idea. She brought together several people: Galia Kremen, Faina Kogan, Natasha Katz, Zhenia Khaita, Nizhnikova and I. We decided to hold demonstrations; the first was in May 1977 during the investigative stage of Shcharansky’s case. It was our most successful and lengthiest demonstration. We stood for six minutes near the Kremlin’s Borovitskii gates with large placards: “Let us go to Israel.” We waited while a group of tourists came down together with their guide and approached the gates, and then we unfurled our signs. A large crowd gathered momentarily. It was a pleasant May evening, the KGB men, were no longer in the garden, leaving, evidently, only the regular guard. Until they phoned, and this and that…. And then like peas they poured down on that hillock and took us to the police station.

They picked you up and then let you go?

Yes. We then held another demonstration at Trubnaia Square. A case had already been opened against Ida but she didn’t care…. This demonstration was unsuccessful. It was raining and they quickly dispersed us. Next was a demonstration near the KGB building, but Galka Kremen blabbed to an acquaintance and, evidently, he “squealed.” KGB plants were already there; there were women heating up the crowd, chanting: “Beat up the Yids and save Russia.” Quickly a van was driven up….

The final demonstration, already without Ida, took place on January 4, 1979. I remember precisely because it was the same day that the “hijackers” were released. A larger number of people than previously demonstrated at the threshold of the Interior Ministry. Levka Blitshtein, who worked nearby, happened to be in the crowd. Later he told me, “Natalia, I never experienced such fear in my life.” A huge crowd gathered, the trolleybuses were stopped, and the crowd roared: “Beat up all the Yids! Kick them all out!” It was awful. We were saved by one thing─the exceptional discipline of Soviet citizens. We were standing on the Ministry’s steps and no one trespassed on those five steps. We were taken to the police station. After we were released, I phoned home and Gena said to me, “Natasha, there’s a telegram. Zalmanson and the other fellows have been released. I’m home.”

Your house was always full of people passing through. How did you hold up under all this?

Each one needed something. A person would call and say…. I’d say, “Come, we’ll talk, we’ll show you what to write and to whom.”

You didn’t deal with prisoners along with Dina?

No. She left in 1978, before our first demonstration. Dina and I studied Hebrew with Shakhnovskii. Slepak and Shcharansky also studied there…. They were, of course, some terribly indolent and sloppy students. People were more interested in politics at the lessons. When Tolik was taken, Dina said to me, “Natasha, you will now receive a visa, so leave Gena’s winter coat for Tolik because he has nothing to wear.” My work relations with Dina were connected only with the lists and similar matters.

Were you ever detained for a day?

No, I had a young child.

So you dealt with all this right up to your very departure─an open house, consultation center, prisoners?

Yes. When Ida returned from exile, I asked her whether she wanted to return to those matters but it was clear that she would be kicked out of Moscow and her opportunities would be limited. She, indeed, wanted to head it again but she was expelled from Moscow.

In Moscow did you have a direct link to the Liaison Bureau?

Yes, but I never was oriented only toward the Bureau; I gave information to everyone who wanted it. I had a regular telephone channel with Dina once a week.

Irina Gildengorn organized another women’s group in Moscow in 1978. Now she lives with her family in Los Angeles.

How did you come to organize a women’s group? I asked her.[8]

It was clear that the men were more vulnerable than the women. They couldn’t harass us on account of army service or “parasitism,” especially if there were little children. We applied for an exit visa in 1977 and from that moment, we had no peace. On March 8, 1978, we went to the first women’s demonstration.

Who formed the nucleus of your group?

I suggested that Roza Yoffe, Natasha Rozenshstein, Lena Dubianskaia, and Maia Riabkina─well, everyone who lived in the Beliavo area [of Moscow], join. There were five women in the initiative group. Many more participated in the demonstrations. We held a press conference, at which I reported on the creation of the women’s group. I made the acquaintance there of Dan Fisher, the Los Angeles Times correspondent, who was still new and didn’t know Russian well; the fact that we spoke English pleased him. We decided to demonstrate on March 8 [International Women’s Day]. Twenty-five people expressed a willingness to participate but only five reached the spot.

After that, we changed our strategy. We decided that we would demonstrate less frequently but more forcefully and our primary activity would be working with women and children and helping families. I was the most veteran refusenik in our initiative group and I knew that foreigners visit only well-known refuseniks. We began to compile lists of refuseniks and asked foreigners to visit everyone on the lists, not just one and the same addresses. “You don’t benefit them,” we said, and you only deprive the others of moral and material support. In order to collect addresses for our lists we would stand near OVIR on Mondays, the day they usually handed out visas or refusals.

I think Dina Beilina dealt with that.

She used to go to OVIR before us, but she did not go regularly. We were already a group and we decided that we would take turns going there, as if to work. We would compile lists of refuseniks and transmit them to the West, using our connections. We knew people in the American Embassy and Dan Fisher.

On May 25, 1978, twenty-four refusenik women sent a letter to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet stating that on June 1, the International Day in Defense of the Child, they intended to demonstrate together with their children. On the eve, on May 31, the women gathered at two apartments─the Rozenshteins and Tsirlins. On the same evening the homes were encircled by the police. The next day no one was allowed onto the street from those apartments and the traffic in front of the homes was halted. The women then carried out demonstrations in the apartments, placing signs with their demands in the open windows and chanting, “Visas to Israel!” The demonstration lasted about twenty minutes during which time the police kept trying to break down the doors. Ida Nudel and the Slepaks joined in by demonstrating in their apartments. Ida hung up a sign on the balcony door saying “KGB─give us a visa to Israel.”

On what floors were you? I asked Irina Gildengorn

On the eighth and ninth. They dropped hooks from the roof in an effort to tear up the placards. We were eleven women and six or eight children. Approximately the same number of people were in other apartments.

What was the outcome of your demonstration?

In the course of a year almost all the members of the initiative group received exit visas. We also attended trials and conducted a hunger strike.

Vladimir and Masha Slepak were arrested after the balcony demonstration. Volodia was then transferred to Butyrka prison but Masha, on June 3, after an attack of angina pectoris and pancreatitis, was sent home under house arrest. A file was opened against both on a charge of “malicious hooliganism.” The same charge was brought against Ida Nudel but she remained at liberty until the trial and even participated in demonstrations. Slepak was eventually sentenced to five years of exile, Nudel to four years of exile, and Masha Slepak to a suspended sentence of three years of exile.

Were you trying to create a scandal in the very center of Moscow? I asked Vladimir Slepak.

I’ll tell you why I did this─because our younger son, Leonid, was in a desperate situation. He had refused to serve in the army, writing a letter to Defense Minister Ustinov saying that as an Israeli citizen he could not serve in the Soviet army. He was in danger of being arrested at any moment. Incidentally, that aspect of my calculation was justified: he was let out.[9]

Was your other son Sanya already in Israel?

Yes, and Leonid was in hiding. At that time he was in Yerevan [Armenia] and later in Leningrad.

Were you treated normally in prison?

Yes, even with respect.

What about during the trial?

I was given a state-appointed lawyer, and I had the impression that he truly wanted to help me, but I told him explicitly: “I shall be happy to cooperate with you up until the trial; you may supply me with advice, codices, and the texts of laws, but at the trial itself, I shall refuse your services. If you will say what I want you to say, you would be expelled from the Party and the collegium of lawyers, and you probably wouldn’t agree to that.”

Where were you sent into exile?

To Chita Oblast, which is fifty kilometers from the place where Ghengis Khan was born. The climate was such that in the winter it was the windiest place in the Soviet Union because it is situated between two ridges; there is not one tree and the humidity is around 10 percent. The snow falls in winter and in the course of a day is converted into vapor. Just the bare sand remains. And this is at 45 degrees below zero. A terrible frost. In summer, when the wind changes direction and blows from the Gobi desert, the temperature then is 38 to 40 degrees centigrade. The ground water is found at a depth of 150 to200 meters. Nomadic shepherds live in this “joyful” place.

There are no cities?

There is one, the center of the district and region, with about 8000 residents. That is a little larger than the village in which I was located; it was called Tokhtokhangil.

Were you supplied normally with clothing and food products?

Masha brought things, and I was able to purchase something in the store. Meat, in fact, was available only in summer. Why bother to sell it in the winter, if you can keep it frozen. We were the first Jews that they had ever seen. They would come to look at us and were astonished that we did not have horns and hooves….

One of the central figures involved in refusenik mutual help, as well as in many other matters in the northern capital, was one of the most veteran Leningrad refuseniks, Aba Taratuta.

Were you in the center of all activities, Aba? I asked him.

There were several centers in Leningrad. The two religious ones were those of Iza Kogan and Grisha Vasserman. Somewhat separate were the Hebrew teachers Yosif Radomyselskii, Leonid Zeliger, and Grisha Genusov. Those centers were based on interests. In addition, there were links of friendship, Purimspiels, amateur entertainment, and libraries.[10]

How did you resolve material problems?

On the person level, my wife Ida is a professional translator. Having been trained by a remarkable English teacher, she was not embarrassed to take ten rubles from students for an hour-long lesson. Those who wanted to go to the West were willing to pay. For a Hebrew lesson, people took a ruble. Help was extended to others in the following manner: A person who asked for an invitation from Israel automatically received together with the invitation─or sometimes instead of it because the invitation might not get through─a package from London from the well-known firm Dinnerman and Company.

There were even cases when individuals didn’t plan to leave but ordered an invitation in order to receive the parcel. People used to come to me indignantly: “What kind of a thing is this? We must expose them!” I calmed them down: “What’s so bad about it? They will tell their relatives and friends that the Jews in the West are helping the Jews of the Soviet Union. Let them receive. How many of them are there? Not so many.” That was the start. Sometimes people helped directly. For example, I remember Irene Manekovsky’s visits. Sitting in our home, for each one who arrived, she wrote out a check of twenty-five dollars, which then had to be exchanged for a certificate. A rather large number of people would come. As far as I know, there was no regular, directed aid in Leningrad. The help was chaotic and occasional. Many tourists visited. We even kept a guest book that shows that people would come on the average once a week. The tourists brought jeans, cameras, and clothing, things that we could distribute to people.

In 1975 we developed very close relations with Lynn Singer, who later became the president of the Union of Councils. Our telephone was soon disconnected but she would summon us by telegram to the post office and that link continued without problems during our time in refusal. We transmitted all the information to her and she sent tourists to us. She helped when we needed to buy a valuable Jewish library of eight hundred volumes. The owner sold it for three thousand dollars. He left us the library and when he arrived in America, he received the money. The library operated all the time, not in my house, of course. When I made aliya, I left it to Boria Kelman. Subsequently, in the period of perestroika, it landed in the Jewish Cultural Center in the Kirov Cultural House. We then purchased another library and even shared the books with the Muscovites. When we distributed things among the refuseniks, we would say that it was from Lynn Singer and that we were only the postmen. When rumors started that some people were receiving too much and others too little and that we should fight against this, we said: “No, we won’t fight with anyone. Let them be well.” Then one semi-Mafia type in Leningrad suggested uniting efforts and organizing a centralized collection and distribution of aid. I said: “No, I won’t participate in that.”

How was aid to the prisoners of Zion organized?

We sent packages to those in exile─to Slepak and Brailovskii. We even tried to make contact with Ida Nudel but there was a period when she didn’t want to be in contact with us. Later we visited her in Bendery. Of the others, we took Mark Nashpits under our wing. His wife left for Israel, and Boria Granovskii and I went to visit him. Non-relatives were also permitted to have short meetings. We were allowed two hours. Before that I accompanied Dymshits’ wife to a visit.

Did anyone ask you to visit him?

No. I just got up and went. Later we dealt with Alik Zelichenok but that was in 1985. Subsequently, Volodia Lifshits was arrested in 1986; both received three years for “slander” and got out on an amnesty under Gorbachev. Those were all seminar cases. First the seminar was at Zelichenok’s place and then it moved to Lifshits.

One of the useful things that I managed to achieve was a struggle against spymania. Rumors abounded and they were spread not only by our brethren but also by hostile organizations. I said: “The hell with the squealers. They [the KGB] know everything anyhow.” And what they shouldn’t know, no one knew.

From 1974-79, twenty-one Jewish activists from across the USSR were sentenced to various terms. In refusal, however, prison was not the worst thing. The real tragedy occurred when the heart failed or, on occasion, when people could not withstand the many years of stress and became mentally ill.

In Minsk three retired front line officers enjoyed great moral authority─the colonels Naum Olshanskii, Lev Ovsishcher, and Efim Davidovich. We affectionately called them the “Minsk colonels.”

What was the cause of Davidovich’s death? I asked Colonel Ovsishcher.

A heart attack.[11]

He looked like a very strong person.

He was indeed a strong and courageous person. Olshanskii was let out of the country quickly but a criminal charge was filed against us for “slandering Soviet reality” and for “dissemination”….

Efim Davidovich was born in Minsk in 1924. He was seventeen years old when World War II started in the USSR. He volunteered to fight and earned many awards. He then continued to serve in the army and retired with the rank of colonel. In 1972, Davidovich applied for an exit visa. He was summoned to the Central Committee of the Belarussian Communist Party, and the KGB conducted “Case no.97”against Davidovich and two other officers who had declared their desire to immigrate to Israel. Davidovich’s health was ruined over four months of an unremitting and exhausting investigation.

His story was widely publicized in the West and he was told that although he was guilty, his case would be halted, “in consideration of the state of his health and his military services to the motherland.”

In 1975, Davidovich spoke at a meeting dedicated to the memory of the victims of Nazism in the Minsk ghetto. Appearing in an army jacket decorated with his military medals, he spoke about antisemitism and the persecution of the Jews by the Nazis and Belarussians. Following this, he had to endure harassment and foul tricks: he was demoted to the rank and file; his home telephone was disconnected; and vicious articles about him appeared in the press. Deprived of his military pension and left without a means of existence, Davidovich developed serious heart problems. In March 1976, after his fifth heart attack, he was denied treatment in a military hospital. The refuseniks sent a collective appeal to the authorities to allow the Davidovich family to leave on the basis of humanitarian considerations. He again received a refusal. Efim Davidovich received this refusal as a death sentence, which, unfortunately, was correct.

Davidovich’s death aroused a storm of indignation in refusenik circles. A large group of refuseniks from many cities came to his funeral. His open casket was carried by Jews through the streets of Minsk. KGB representatives were present at the funeral but chose not to interfere. Naum Olshanskii, the only one of the three colonels who had left for Israel, said: “He fought against antisemitism with the same courage and determination that he had demonstrated in the war against fascism. He was the best and bravest among us….”

In Novosibirsk the Poltinnikov family of refuseniks enjoyed great respect. They spent nine years in refusal during which time they endured many difficult situations. The women’s nervous system did not hold up under the strain.

What did Isaak Poltinnikov do? I asked the former Novosibirsk resident and well-known activist and prisoner of Zion, Feliks Kochubievskii.

Poltinnikov was an ophthalmologist, a colonel in the army’s medical corps and chief ophthalmologist of the Western Siberia military region─a high-class specialist who treated the regional commander. He developed a method for treating tuberculosis of the eyes, performed about three thousand operations, and a chair of ophthalmology was held for him in a medical institute. After his release from the army, he went to work as a regular doctor in a clinic for railroad workers and then applied for an exit visa for himself, his wife, and two daughters.[12]

I heard that when he received a visa, he left on his own.

This was the most tragic story of refusal that I know of. The mother found a fictitious fiancé for the younger daughter Ella. They were married and left, I think, in 1970. After arriving in Israel, Ella divorced her “husband” and married Avraam Shifrin. They had two children. Isaak remained in Novosibirsk with his wife and daughter, who also were doctors. They actively fought to leave. After many long years of persecution, tailing, and fifteen-day arrests, the women began to show signs of paranoia. They imagined KGB agents everywhere and all kinds of intrigues, even when they didn’t exist. In the winter of 1979, I learned that OVIR was giving them an exit visa. I did not know them personally but I heard of it from their acquaintance, a veteran refusenik, Cherna Goldrot. The women, however no longer trusted this visa and considered it a KGB provocation to draw them out into the street. At that time they no longer went out of the house.

How did they live?!