After the signing of the Helsinki Final Act (August 1, 1975), the number of exit visas that were issued rose slowly but surely, reaching 51,331 in1979. Inparallel, the quality of samizdat improved and the quantity increased. In addition to the journal Jews in the USSR (Evrei v SSSR, 1972-80), other journals that appeared in Moscow included Tarbut (Hebrew for culture,1975-80), Our Hebrew (Nash ivrit, 1978-80), Jews in the Contemporary World (Evrei v sovremennom mire, 1978-81), and Departure to Israel (Vyezd v Izrail, 1979-80). Riga Jews produced the journals Din umetsiut (Hebrew for law and reality, 1979-80) and Haim (Hebrew for life, 1976-86).

In this period, the activity of the refusenik seminars intensified, new ones were added, and they were established in additional regions. Legal, humanitarian, scientific, and teaching seminars arose in various cities.

The network of ulpans for Hebrew study expanded considerably and the quality of instruction improved.Moscowteachers extended their activity to other cities. InMoscowthe number of so-called “diburim”─organized groups of teachers and advanced students in which lectures and discussions were conducted in Hebrew─continued to increase. A seminar for Hebrew teachers began operating in 1977.

Diburim

The basic goal of the “dibur” (from the Hebrew word “speech”) was to create the conditions for conversational language practice. One could arrange a friendly meal at a “dibur” as Zeev Deborin and Vladimir Shakhnovskii used to do in 1972, speak about various topics over a cup of tea as was the practice at the “diburim” of Mikhail Goldblatt in 1973-74, or listen to interesting reports and sip tea with pies as was customary at Lev Ulanovskii’s place from 1975-79.

A graduate of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Lev Ulanovskii had an excellent mastery of several languages, including Hebrew, which he began to study long before applying for an exit visa. Not limiting his teaching activity toMoscow, Lev also made the rounds of other cities. His pupils include many prominent figures such as Aleksandr (Ephraim) Khomianskii, Yulii Edelshtein, and Aleksandr Yakir.

Where did all this Zionism come from? I asked Ulanovskii.

From my family. My father was always a Zionist, although he manifested this only in a narrow circle. He was proud of his Jewishness, knew Yiddish, and disliked communism, attitudes that he conveyed to me. He himself took after his parents. Back in the early 1920s, they planned to follow Bialik toPalestineand even accompanied him to the harbor when he left. The opportunity to leave, however, was soon blocked.

When did you apply for an exit visa?

The departure toIsraelin 1973 [of his father and family members] showed that it was possible to leave. I immediately asked my father to send me an invitation and I began to study Hebrew with Zeev Shakhnovskii. I submitted documents in 1974 and received a refusal on the grounds that it was “not expedient.”

When did you begin to teach Hebrew?

Even before applying for a visa. Having already studied several languages, I understood the importance of conversational practice. With the help ofLenaand Zeev Shakhnovskii, I rather quickly organized a weekly “dibur” at my place, a kind of salon in which only Hebrew was spoken.

Were there many participants?

Hebrew study turned into a mass phenomenon inMoscowand our “dibur” became popular. As word about it spread abroad, Hebrew-speaking tourists began to show up regularly. We and our guests would deliver lectures in Hebrew.

What topics were raised?

Various topics such as Jewish history, Judaism, Hebrew grammar, contemporaryIsrael, literature, ethics, and so forth. After the lecture we would drink tea with pies. It was noisy and cheerful. Everything was done openly, without secrets or conspiracies. Anyone, even a stranger, could come as long as he spoke Hebrew.

The KGB didn’t interfere?

Everyone understood that the KGB would send its agents to us. We didn’t object, considering that the KGB also should study Hebrew. Earlier “diburim” had been closed ones to which only acquaintances were invited. The novelty of my “dibur” was its complete openness. The walls of the apartment were covered with Israeli postcards, leaving no free space. People would come to see the pictures ofIsrael. Maps were added to the wall and books to the shelves. I opened a mini-library, assuming that the more the books were in people’s hands, the less the chance of their being confiscated in a search. My apartment started to resemble a smallmuseumofIsrael. Soon “diburim” like mine sprung up in other homes. We tried to divide them into levels for advanced and beginners. For the youth who visited us fromAmericaand Europe, it was aschoolofZionism, a reflection of the Ben Yehuda period but transposed toMoscowof the 1970s. It made a strong impression on them. They often said that we helped them no less than they helped us. Professors would come fromAmerica, Europe, andIsraelto deliver one or a series of lectures on topics ranging fromIsrael’s archaeology or fauna to computer simulation of Hebrew grammar. Rabbis, politicians, and journalists arrived singly or in groups. Isi Leibler brought Bob Hawke, who soon became the prime minister of Australia. Not all of the guests knew Hebrew and I would have to translate.

Lev, I was told that you conducted other activities, too.

Yes, we held daily readings of the Torah at my house, also in Hebrew, under the direction of Zeev Shakhnovksii, who had an unusual talent for this. For the majority of Muscovites, who were unfamiliar with the Torah, it opened a new world. A small but rapidly growing circle of young Jews who were discovering religion appeared.

Under the influence of Habad?

I don’t know about Habad. Shakhnovskii and I studied and discussed Torah and Gemorrah [the Talmud] only in Hebrew. Incidentally, we used the Steinsaltz edition of the Gemorrah. As far as I know, Essas’ style of studying was different. He conducted lessons in Russian and the primary focus was on attracting the students to religion. We, in contrast, studied the texts themselves.

You were one of the first who extended teaching activity beyond the Moscow limits.

It happened naturally. Hebrew teachers would come to the “diburim” from other cities such asLeningrad,Vilnius,Minsk,Dushanbe,Riga, andFrunze. I then began to travel to them. I used to go toLeningrad,Vilnius,Minsk, andDushanbe. Now it’s hard to remember all of the places. We tried as much as possible to operate openly and not to create an “organization.” I also tried unsuccessfully to register officially as a Hebrew teacher and pay taxes as such. With rare exceptions, the level of Hebrew was much lower outside ofMoscow. Do you recall, Yulii, you and I organized the first summer camp for Hebrew teachers from various cities at Koktebel? Around ten people came. It was great: songs, jokes, fun, rocks in the sea, the near-by mountainpeakofSiuriu-Kaiaand Hebrew, Hebrew, and more Hebrew. A year later, in 1980, I was already inIsraeland heard that the participants in that camp increased tenfold. They were in heaven and you were jailed for fifteen days.

The KGB reacted sharply to the teaching for out-of-towners.

Yes, when I heard that you were arrested, I was already inIsrael. I felt guilty that I was no longer with you. I traveled around the world, telling people your story, but the guilty feeling remained. I remember once inStockholmjust after a phone conversation withMoscowwith the families of those who had been detained, I was placed in front of a microphone. I was in tears and felt ashamed in front of the audience.

The Hebrew Teachers’ Seminar, 1977-84

In 1977, I organized a seminar of Hebrew teachers that differed from previous humanitarian seminars primarily in that all sessions were conducted only in Hebrew. In that sense it became the successor of the “diburim.” I, too, started a “dibur” for my advanced students. At the seminar, we basically discussed, studied, and elaborated ideas for teaching Hebrew that seemed effective to us─a topic that was inexhaustible and very creative under Soviet conditions, and we also heard lectures and reports of common interest. The main seminar participants were Hebrew teachers fromMoscowand other cities and also advanced students, many of whom would soon become teachers. The seminar thus turned into a creative laboratory in which the most effective Hebrew teaching methods, the best textbooks, and auxiliary material were selected and approved.

Aside from those differences, the teachers’ seminar resembled all the others. Each session consisted of one or two lectures, followed by a discussion. The reports were prepared by the best Moscow Hebrew teachers or by guests from abroad. Among theMoscowteachers and lecturers were Mikhail Chlenov, Lev Gorodetskii, Yulii Edelshtein, Aleksandr and Mikhail Kholmianskii, Lev Ulanovskii, Ilya Essas, Evgenii Grechanovskii, and Aleksandr Ostronov. Of course, we also had cultural reports on Jewish holidays, various aspects of life inIsrael, and religious topics. While still on the level of a “dibur,” the seminar very quickly became a popular meeting place for those who wanted to make progress in Hebrew, were interested in spreading knowledge of the language around the country, and wanted to study contemporary Jewish culture in its original language.

My dissatisfaction with the level of the “dibur” and desire to organize a seminar derived from the “incorrect” teaching of foreign languages in theUSSRin general and its negative effect on the Hebrew ulpans in particular. In theSoviet Union, languages were generally studied in order to translate some of the West’s technological, scientific, and cultural achievements into Russian. As contact with foreigners was not encouraged in the closed totalitarian state, conversational language was practically not taught. Instruction focused on grammar and the endless search for the exact equivalents of foreign expressions in Russian. We, however, faced completely different tasks: teaching our students actively to utilize a basic vocabulary, teaching situational conduct in the language, and, in essence, showing them how to live in Hebrew. We had to protect our students from useless and time-consuming attempts to master Hebrew according to the Soviet methodology. I considered that, as in young children’s language acquisition, conversation should precede other forms of linguistic activity. We also dealt with reading and writing, but generally on the basis of conversational material that had already been mastered.

The basic topics of the seminar included various methodologies of foreign language instruction; textbooks; the characteristics of human memory and the best methods of mastering material; aspects of linguistic activity; situational conduct in a language; the linguistic peculiarities of Hebrew; grammar; various levels of the lexicon─the language of the Torah, contemporary Hebrew, slang, and substandard language; poetry in Hebrew, the interaction of Hebrew with other languages; and so forth.

We barely dealt with problems of pronunciation. Hebrew was revived by immigrants fromRussiawith their particular pronunciation. People inIsrael, a multilingual country of immigrants, speak with a wide range of accents, thus rendering differences in pronunciation the norm rather than a violation of strict rules. Those who wanted to practice their pronunciation had the opportunity to speak with Israelis, who were frequent guests at the seminar, or to listen toIsraelradio. It was assumed that neither Russian nor English would be spoken at the seminar. All reports and discussions would be conducted only in Hebrew without any exceptions. On the one hand, that requirement would energize people to reach the necessary level more rapidly and, on the other hand, it would weed out the idlers who could ruin the seminar’s special atmosphere.

For several years the seminar was held at the hospitable apartment of Irina Abramovna Nekrasova, whose son Misha was one of my successful students and also a teacher. Usually about twenty to thirty people, primarily Hebrew teachers, attended a session. Up to fifty or more people would crowd in to listen to the reports on history and culture. The seminar quickly attained recognition domestically and abroad. We listened with particular interest to reports by guests fromIsrael, who usually were official guests of theSoviet Unionthat had arrived for a scientific conference, international book fair, and so forth. Frequently, the guests held dual citizenship. Beginning in 1978, I was able to arrange for the arrival of lecturers on specific topics. The seminar gradually produced a group of well-informed, highly motivated, and Zionist-oriented people.

Israelbegan to take part inMoscow’s biennial international book fairs from 1977. Two Israeli participants arrived for the first one, but the delegation grew each time and numbered seven people in 1985. The delegation’s two-week stay inMoscowprovided an opportunity to gain familiarity with Israelis, Israeli culture, and Israeli books. We prepared carefully for each fair, informing people inMoscowand other cities, and we arranged meetings with members of the Israeli delegation. The Israeli pavilion was always the most popular at the fair; the long line for it wound around the aisles between other pavilions. The Israelis were generous, willingly sharing books from the exhibition, Israeli souvenirs, and lapel pins. Before their trip the women in the delegation would make for themselves necklaces of hundreds of Stars of David and pins, which they then distributed at every meeting.

I had forged good ties with teachers from the provinces who, when they visitedMoscow, would try to attend the seminar. If out-of-towners arrived for two to three weeks or more, I would organize a course of intensive lessons for them with one of my students and supply text books and technical support.

The number of well-trained Hebrew teachers inMoscowbegan to increase rather rapidly. We estimated that by the end of the 1970s, there were over one hundred teachers and over a thousand people studying inMoscowulpans.

The level of instruction in the provinces was considerably lower than in the capital at that time. I thought more and more about how to help them, discussing some ideas with Israelis and Moscow Hebrew teachers. In talking with Lev Ulanovskii, who had some experience in teaching in other cities, we developed a concrete proposal to combine vacation time with intensive training of out-of-town teachers at Koktebel on the Crimean shore. We implemented our plan in the fall of 1979. Nine teachers arrived fromMoscow,Minsk, andLeningrad, studying for six hours a day: three in the morning and three in the evening. The rest of the time was taken up with hiking and swimming. I familiarized them with my teaching ideas, with audio and audiovisual courses, and with textbooks. A month of studies flew by, no one hindered us, and we decided to operate the same course the following fall.

The next year, 56 Hebrew teachers fromMoscow,Leningrad,Odessa,Minsk,Chernovtsy,Tashkent,Kiev, Tiblisi, andSverdlovskattended. We divided them into eight groups and began intensive studies.

In 1980, however, relations between theUSSRand the West cooled sharply in connection with the Soviet invasion ofAfghanistan. We could feel this already in Koktebel. I was provoked and arrested for fifteen days and the intensive training course had to be cut short, but that’s a separate story.

Mikhail Nudler’s Seminar on Jewish Culture, 1977-78

Mikhail Nudler organized and conducted a seminar on Jewish culture in1977. Agraduate of MGU, he was still quite young, loved to play ball at “Ovrazhki,” and led a cultural program there together with Volvovskii. Not having applied for a visa, he was actively involved in samizdat work, would appear in a Purim spiel ensemble where he invariably played the role of King Ahashverus, and, in general, engaged in a multitude of activities.

You added a seminar to all your other activities? I asked Misha Nudler.

At the time, there was no seminar for youth. Moreover, as far as I recall, all the other seminars were oriented primarily toward refuseniks. Non-refuseniks, especially the young and vulnerable, were advised not to attend them. I was rather involved in various matters but I was not a refusenik and had not yet applied for an exit visa. There were many like me. I felt that there was a need for a seminar serving that circle of people. At the first session, which took place at the end of October 1977, there were six people in all, but the number rose sharply with the second session. People would come directly from the synagogue. From forty to fifty people would crowd into my one-room apartment.

Who gave the reports?

Deciding that we would not be both organizers and lecturers, we invited speakers. Misha Pontilias gave a report on Hanukah, Volodia Prestin on ways to resolve conflict situations, Mika Chlenov on the co-existence of the Russian and Hebrew languages over the centuries, and Albrekht on his book How to be a Witness at an Interrogation, and many others. The cultural program moved to Ovrazhki in the summer.

Leningrad

Leningradsuffered the most from the wave of legal repressions in 1970-71. Many activists were charged in the First and Second Leningrad Trials, three were included in the Kishinev Trial; hundreds were summoned to interrogations; and many searches were carried out. As a result, the development of social and cultural activity in Leningradat the beginning of the 1970s was significantly slowed down but not entirely eliminated. People continued to apply for exit visas, and activists, generally not linked to the sixties generation, renewed the preparation and distribution of samizdat and Hebrew instruction. Many people would gather near the synagogue on holidays, a refusenik mutual help system began to function, and seminars appeared. There was a large gap in periodical journals─until 1982 but the LEA (Leningrad Jewish Almanac) that was started then was noted for its high quality.

Feliks Aronovich’s seminar on Jewish culture, 1975-77

TheLeningradactivist Aba Taratuta notes that in 1975 Feliks Aronovich initiated the first seminar there on Jewish culture. Aronovich was also the principal lecturer. I sought him out inChicago.

What influenced your choice of the seminar’s direction? I asked him.

My respect for history and the desire to revive it in others. For example, I prepared a report on the reflection of Biblical history in paintings in the HermitageMuseum.[1]

How often did you meet?

As soon as the next report was ready. On the average, once a month. People were invited with their children. This created a certain legal problem as it could be interpreted as “religious propaganda.” The reports, therefore, adhered to a cultural style. About twenty-five people would gather together, primarily active refuseniks.

Did Israel attract you?

Yes, naturally, we were concerned about it. Having joined the list of refuseniks, we felt a joyous immersion in Zionism.

Did the KGB exert pressure?

Of course. My mother, who was a lawyer, was very fearful about what might happen to me. A half year after our refusal, mama and my younger brother received exit visas and went toIsrael. She knew that I would not sit passively. She left me a copy of the criminal code and implored me not to violate it, and I acted accordingly.

Did you halt the seminar because of pressure?

No, I simply lost the desire to prepare reports after a couple of years.

Who else prepared reports besides you?

Shura Boguslavskii gave the most interesting report on how the Jews became Jews.

Did you go directly to the States?

Yes, because at that time my mother and brother leftIsraeland I had already sent my wife to them.

The engineering-technological seminar of Granovskii-Taratuta-Kagan, 1976-81

An engineering-technological seminar operated in Leningradfrom 1976 to 1981. Aba Taratuta told me about it with a smile:[2]

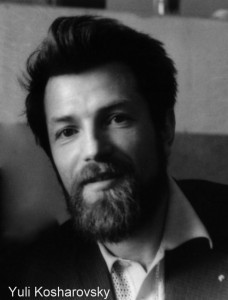

Incidentally, you have a direct relationship to it. ALeningradactivist, Boris Cherniakov, a lecturer at the Leningrad Machine Tooling Institute, traveled toMoscowand on his return told me that Kosharovskii had an interesting engineering seminar. That was in 1975, when many scientists were in refusal. The mathematician Boria Granovskii and I began to think: “Why shouldn’t we organize such a thing?” We did, and it opened in November, 1976. I have even kept the program and list of lectures that were delivered. It was a technical seminar designed to help people maintain a professional level. People didn’t announce scientific discoveries there.

How many attended?

Around ten to twelve. We met weekly on Mondays. In 1979, Granovskii received an exit visa.

Was he the formal leader?

Yes, but around the time of his departure, new people appeared, for example, Abram Kagan, a prominent specialist in statistics. He became the leader of the seminar and eventually agreed to hold it in his home. It continued there for over two years and then stopped.

Segal’s legal seminar, 1977-79

That was not the sole seminar in my apartment, Taratuta told me. In parallel with the engineering seminar, we held a legal seminar starting in 1977. It was led by Valera Segal, a lawyer who had been imprisoned although not for Zionism. He accomplished inLeningradapproximately the same thing as Albrekht inMoscow: he instilled in our ranks the ideas that one need not always fear the KGB; they have their own legal restrictions, and if, for example a policeman rings the door bell, it’s not at all obligatory to let him into the house. Very useful.

He would deliver his lecture and then people asked questions. In addition, once a week he would sit near my telephone and give advice on legal issues.

How long did the legal seminar continue?

Not more than two years. In 1978, the humanitarian seminar of Grisha Kanovich (not to be confused with his exact namesake, the writer fromVilnius) began to operate.

Grigorii Kanovich’s humanitarian seminar, 1978-81

Kanovich’s seminar, which was very popular inLeningrad, was able to unite capable, enterprising people who matured and developed together with the seminar. It was a new generation of activists, rarely connected to those of the late 1960s.

I heard that there were several forceful activists at the humanitarian seminar, I noted to Aba Taratuta, seeking an explanation.

Yes, Yasha [Yakov] Gorodetskii, Lev Utevskii, and Misha Beizer, but Grigorii Kanovich, of course, organized it. He is a historian, a graduate of a pedagogical institute. In the 1960s as a result of his involvement in dissidence, he retrained as a computer programmer. Incidentally, he predicted the collapse of theSoviet Unionvery accurately.

Grigorii Kanovich (1934) grew up without his father, who perished at the front. He

matured in the period of the antisemitic Stalinist trials that traumatized an entire generation of Soviet Jews, including him.

I heard that you became interested in dissidence, I began the interview.

I entered an institute in 1950 and studied during those terrible years. Naturally, I did not accept what was happening. The “great leader” died when I was nineteen years old. I was assigned a job in theSverdlovskregion, where I worked for a year as a teacher and then two years as the assistant principal of a high school. My dissident leanings began after I returned toLeningrad. I wrote three works that circulated around the country. In 1968-69 the club “Parus” was popular inLeningrad. I went there and after a month, I became its director. Up to a thousand people would gather in the large auditorium of the Vyborg House of Culture. In 1970, however, I decided to break with dissidence: it’s not the Jew’s business to resolveRussia’s internal problems.

When did you apply for an exit visa?

In 1977. We received a refusal because my wife worked in a place that was classified. [skipped line]

What gave you the idea for the seminar?

On our days off we would go to enjoy nature at Sestroretsk. We were often accompanied by guests─American or English Jews. They would try to educate us, relating all kinds of historical material, and sometimes they gave reports. I myself am a historian and felt that something was lacking─to put it mildly, those people were dilettantes and either spoke a limping Russian or needed translation. I then went to Lev and said: “If people are interested, then let me give you everything that you want. We don’t need to torture the Americans.” And I began to deliver lectures.

Where?

In Sestroretsk, in a natural setting.

Did a lot of people come?

At first twenty to thirty. Taratuta, Kogan, and Furman helped me with literature in English. Grisha Vasserman undertook religious topics and I handled historical ones.

Did you meet regularly?

Once every two weeks. At the end of each session, we announced the next topic and location of the following seminar. Apartments were always available and the number of participants and of lecturers constantly rose. Once Lev Utevskii got us and said some very intelligent things, and, as we say, he didn’t sit down again. Up to one hundred people would gather for the seminar. After about a year, we settled on two apartments─mine and Vasserman’s, identical one-room Khrushchev-era slums. I don’t know how people squeezed in them but they did.

When did you receive a visa?

In March, 1981.

Mikhail Beizer (1950), an active participant in the seminar and today a lecturer at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was one of the few who had links with the Leningrad Zionist activity of the 1960s. In his opinion, Kanovich’s seminar was particularly important for theLeningradrefusenik community. When the authorities dispersed the seminar, Beizer renewed it but in a somewhat different form.

Kanovich and Utevskii in essence revived the Zionist movement in Leningrad, asserted Beizer.[3] They quickly received exit visas. After Kanovich’s departure, Yasha Gorodetskii led it and then he, too, was permitted to leave; I took it on next.

How did you become active?

Grisha Kanovich is a good organizer and excellent debater; he could convince anyone. He was very knowledgeable about the history of Russian Jewry and the history of Zionism. It wasn’t just a matter of knowledge but the way it was presented, the idea behind it. He made a strong impression on me. Utevskii is a different type of person. He spoke about philosophical and religious topics. Vasserman was more and more inclined to orthodox Jewish positions. Even though it was distant and hard to reach, people selflessly attended the seminar. Almost allLeningradactivity in the 1980s was led by people who participated in the seminar.

Did Aba Taratuta attend?

Yes. At the end of the 1970s, there was a small number of older refuseniks: Yurii Shpeizman, Daniel Fradkin, Aba Taratuta, and Lev Kogan. They had connections and they helped Kanovich. The seminar leaders, however, succeeded in cultivating a new generation of activists, which was manifested in 1981 when the regime started to exert pressure on the seminar and conduct massive round-ups. Vasserman was beaten up on the street. During one round-up, almost seventy people were arrested, registered, and photographed, and some were imprisoned for a few days. Evgenii Lein was arrested; apparently he acted too provocatively. On the basis of the reaction to Lein’s arrest, one could say that a movement already existed inLeningrad: no one took fright or ran away; everyone came to the trial. The trial was relatively open and the atmosphere very militant. This trial led to all further developments: the subsequent seminars, my excursions, Leonid Kelbert’s theater, and the journal.

Your excursions around Jewish Leningrad became quite well known.

I didn’t start with that. When the seminar was dispersed, Yakov Gorodetskii decided to continue it, but it was already under great pressure. On the one hand, the authorities were up in arms against it and, on the other hand, there was a serious shortage of lecturers after the departure of Kanovich and Utevskii. Vasserman formed a separate religious group and became involved in other matters. I very much wanted the seminar to continue. At a critical time, when the KGB agents interrupted a session, writing down the names of all the participants, and harassing them, I offered to give some kind of lecture. At that time I had already heard something; I assembled some books and began to read. He let me try and it went well. I managed to deliver a few lectures before the seminar was broken up. Then Albrekht visited us and delivered a lecture on how to conduct oneself at interrogations and searches. That took place at my friend Semyen Frumkin’s apartment.

Is Frumkin a historian?

Together we edited the Leningrad Jewish Almanac [LEA] and participated in seminars. He is an electronic engineer by profession. After the lecture, we remained to drink tea.

Albrekht, commenting that so much had happened inLeningrad, said: “If I lived here, I would lead excursions around historical sites. Not the way the authorities do it, but for real: where the Kadets were, where the Mensheviks were, and what they represented, that is, I would tell the genuine history of the revolution.” He had a bunch of ideas how to annoy the authorities. Later on, I recalled his suggestion. I wasn’t interested in the Kadets or social revolutionaries but more in our Jewish affairs. I carried out rather serious research and started in 1982. Because the seminars had been dispersed and the apartments almost closed, we had to devise a format to carry on our activity in the street.

Mikhail Beizer’s cultural-historical seminar, 1982-87

From 1982 until 1987, continued Beizer, we ran a cultural-historical seminar but of a completely different type. There were three initiatives in which I participated: excursions, the Jewish cultural almanac, which I did not start but in which I published from the first issue, and the cultural-historical seminar.

How did the excursions work?

I worked out three to four routes, conducted research, and then invited people. At first, not many were interested. Sometimes I went with three and other times fifteen. I would stand in the center ofLeningrad, in the middle of Nevskii Prospekt and loudly relate something about the Jews. In winter it was cold and I would take them to warm up and drink some coffee. We walked a long time, occasionally up to four hours.

On foot?

Only on foot. This continued for about two years, in 1982 and 1983. The book The Jews of Petersburg appeared because the excursions were disrupted and friends told me that I should write down my excursion lectures.

How were you dispersed?

The usual way. On the square near the conservatory where I assembled everyone, we were suddenly surrounded by the police and many people in civvies; next, a motorcyclist drove up and began to rev up his motor, not allowing us to speak. Then I noticed that some special unit was following us. It began to look like fifteen-day detentions or more, and there were not only refuseniks but also people with some status with me. I said, “Guys, scatter, or else they’ll detain you.” Then I understood that things were going badly.

Did anyone help you, Misha?

No one financed anything. Although the open seminars had been shut down, interest in them remained, suggesting that they would be renewed in the future. I therefore deemed it necessary to train knowledgeable people and decided to set up such a seminar, which existed for quite a long time. We would meet every two weeks except during the summer. I invited only those who in the future could become lecturers or writers. People were chosen secretly, solely on the basis of recommendations. Each person who wanted to take part in the seminar had to prepare a report, read it, and then give me the text, which went to the journal LEA. The seminar was therefore small, about fifteen people, but over five years we trained them well.

That seminar continued for five years?

I left after five years, but the seminar continued even after my departure.

Misha, you dealt with history?

Primarily Jewish history but not only that. In front of our eyes many participants matured in the course of this seminar. Occasionally Muscovites visited us. Chlenov spoke. Then Natalia Vasilevna Yukhneva, an important historian with an interest in Jewish topics, joined us. She is not Jewish but she was very helpful and I invited her. A journal was published on the basis of the seminar works.

Was your approach purely historical or also Zionist oriented?

The latter was present but not primarily. When I led an excursion, I would note: “You see, in tsarist times when people wanted to go to Argentina, they were helped, they were freed from serving in the army, but we….sit here in refusal…” There were Zionist elements in the excursions, but at the seminar I did not engage in any propaganda. I afforded people the opportunity to study something seriously, to become someone, to learn something about those matters. A report might, for example, deal with the Jewish marriage rite, the ancient temple, or Bogdan Khmelnitskii’s pogroms. No one gave us anything; we didn’t receive any advice, and therefore we did what we considered necessary. We agreed in advance about some matters: not to bring in anyone who would not work actively; not to advertise the seminar; not to invite foreigners; not to distribute at it any money, parcels, or material aid. I didn’t want mercantile people there. I wanted to have people with whom it was interesting to socialize.

Could people who were openly fighting for the right to leave participate in the seminar?

They could. I said: “You can do whatever you want on the street. Throw yourselves on the embrasures, chain yourself atRed Square, but don’t mix my business in there.”

You weren’t afraid that activists could drag their “tails” after them?

At one time, I lived in a communal apartment. My neighbors were a prostitute and alcoholic; all kinds of people used to come to them. We were visited by Jews who sat quietly in the room, didn’t get drunk, and then calmly dispersed. I thought that if the seminar would not receive direct publicity or foreign visitors or carry on financial activity, even if the KGB learned about it, it would not seem important to them.

Humanitarian seminars opened also inKharkov,Riga, andKishinev. The seminars were in contact with each other and exchanged lecturers. The regime’s attitude toward their activity varied. Years of relative tolerance were replaced by periods of harassment and arrests, but the seminars survived and for many years served as centers for a revival of Jewish cultural and scientific activity and as breeding grounds of the collective Zionist struggle.

Jewish Song Ensembles and Purimspiels

The Purimspiels became our act of defiance against our refusenik fate. Merry comedies about the marvelous salvation of the Jewish people in ancientPersiaresonated in an astonishing way with the harsh, everyday refusenik life. Amateur performances were extremely popular, particularly in the gloomy 1980s. The heroes were contemporary and recognizable, and refusal,Israel, and the aliya struggle constituted the basic content.

The first Purimspiel inMoscowwas supposed to take place at Yosif Begun’s apartment on March 1, 1977. I remember that day very well. In the morning, a group of refuseniks were practicing yoga at Yosif’s apartment and we finished around one o’clock. Our hospitable host reminded us that the Purimspiel would begin at seven in the evening and those who wanted could remain. A special delivery messenger arrived at that time and handed Yosif a notice to appear at the district police station. “Don’t go away, I’ll be back soon,” he said. “If you have to, close the door and put the key under the rug.” Yosif returned a year and a half later─thus began his first arrest.

It was impossible to hold the Purimspiel in the absence of the host given those conditions. Toward evening we realized that Yosif would not be let out by the beginning of the performance in order to disrupt it. The performers and audience then went to celebrate at the apartment of “Ahashverus,” Misha Nudler. The Purim show was cheerful and interesting.

Mikhail Nudler was the first and ongoing performer in the role of Ahashverus until his departure in 1980.

Misha, how did you land such an important role in the Purimspiel? I asked him.

Before the Purimspiel there was an ensemble that I once went to hear. Zhenia Finkelberg, Leva Kanevskii, Misha Tigai all sang well. The director was Misha Gorbatov, a professional musician; Leva Kanevskii was the star of the group: a veteran performer of Hebrew songs, he knew about three hundred songs and played the guitar the best of all.[4]

When Hanukah was approaching in 1976, Leva Kanevskii came to me and said: “Hanukah falls almost at the same time as the symposium on culture. It is highly probable that we shall wind up in police detention because of the symposium. Let’s therefore do the following: you will prepare a Hanukah program and keep away from the symposium.” I agreed and that became my first cultural activity.

At Hanukah time I invited everyone to my place; about one hundred people came to my two-room apartment in Orekhovo-Borisov. They came and went. Leva told about Hanukah, we lit the first candle, and we then sang. Three months after that, my first Purimspiel took place.

In fact, the proposal to organize the performance came from Andriusha Okunev. He read in some book that performances used to take place on Purim. I was fired up by the idea and decided to stage a performance using Racine’s seventeenth-century play Esther (1689). I went to the library and copied down the entire night scene in which Haman is exposed. There were three roles in that scene: I gave Haman to Volvovskii and Esther to my sister. She acted in a drama club and had a typical Jewish look.

That was, however, only the first half of the Purimspiel. The second part was a “kapustnik” [a “roast” or revue-sketch comedy]. Fifteen people took part in the revue, which was composed manly of songs.

Around Purim time the next year, I was busy and didn’t have a head for that. Two or three weeks before Purim, Volvovskii phoned and asked: “What about the Purimspiel?” “You know,” I said, “something isn’t jelling for me this year.” He began to yell at me: “What’s the matter with you? All ofMoscowis waiting and something isn’t jelling! Do something so that it jells.” In 1978, we put together a performance at the last moment and it was rather weak. We performed it once at the Rosenshtein’s place. Between those two Purimspiels, I started a seminar on culture that lasted until the summer of 1978.

The theatrical group included a couple─Zhenia and Roza Finkelberg. Zhenia sang and played the violin and guitar and Roza wrote the Purimspiel texts. The composition of the troupe continually changed as people left the country, but the Finkelbergs spent ten creative years in it.

Roza, how did you wind up in the Zionist movement? I asked.[5]

In 1973, I began studying at the Oil Institute. We soon formed our own group, discovering each other at the time of entry exams. On Simchat Torah we decided to go to the synagogue and remained there with companions of our age. We used to meet there every Saturday, where we would find out about demonstrations, meet with various people, and sometimes sign some petitions.

How did you meet Zhenia?

Zhenia studied in an institute and was very…Soviet. As a respectable Komsomol member, he signed up for the national guard. Once they were sent to the synagogue to maintain order. There, indeed, he started to think about what side he ought to be on. At the synagogue he met Volvovskii, talked with him, and the next day wrote a statement resigning from the guard.

We met during one of the trips out of the city in 1975. Kadik Kkruzhkov invited me. We entered the train car but there were no seats so I stood in the corridor. Some pleasant young fellow called me. I thought that he planned to give me his seat, but he placed me on his knees… and thirty years have passed since that time.[6]

Did you have a musical education? I asked Zhenia Finkelberg.

Of course, I studied violin for five years; what do you think─a Jewish boy! But at some point football won and the violin had to be exchanged for something else.

My real encounter with Zionism began with the ensemble. Until then it simply was pleasant to be among Jews, but in the ensemble I already began to feel like one of them. I basically played the guitar and then began to sing along.

You weren’t afraid that the KGB might photograph you?

We had the feeling that we were not doing anything illegal and not bothering anyone. Later on, we became aware of the problems.

In his student years, Leonid Volvovskii played roles in the amateur theater of the Gorkii Polytechnic Institute, was a winner in contests, and then participated in the Gorkii KVN [Russian acronym for “Club of the cheerful and sharp-witted,” satirical competitive teams that existed around the country). He did his graduate work atMoscowStateUniversity, where he acted in the famous Rozovskii student theater. He had boundless energy and there was no end to his jokes.

Was there any connection between the concert at the Rozenshtein’s place, the Purimspiels, and the disrupted cultural symposium? I asked Volvovskii?

No, the performances operated in parallel and began before preparations for the symposium. The cultural symposium was a theoretical initiative. We wanted to show that the Jews had been torn away from their national culture and had no way of gaining access to it.[7]

How long did it take to prepare a performance? I asked Roza Finkelberg, the main scriptwriter for the Purimspiels, who, starting in 1981, wrote all the scenarios for her group.

Not so long; we started preparations about a month to a month and a half in advance. I wanted to write not merely a comic sketch but something that resembled a play with a subject line.[8]

“We really liked the texts of the Purimspiels; they were so humorous.

To a considerable degree that was a result of collective creativity,” interrupted Zhenia. Roza provided the core and then we elaborated on it with our comments, and Roza also─sometimes until tears.

From whence this talent? Roza.

I don’t know. From God, from my mama─she wrote stories─and from a sense of duty. I didn’t want the Purimspiels to fade away. After each performance, we were invited to do the next. In the first week there were several performances a day, then until Pesach, several a week. In the light of this success, other Purimspiels began to appear: the children’s Purimspiel of Mila Kaganova and the one of Vladimir Geizel. Purimspiels were staged at kindergartens. That, indeed, was the gloomy period of refusal. Where, however, does real humor flourish? In a totalitarian state, because so much is forbidden there. It was funny because associations arose, everyone understood the subtext, and laughed from the heart.

What happened to the ensemble?

First of all, it became the foundation for a permanent Purimspiel cast: Sasha and Klara Landsman, Ira Razgon, Zhenia Finkelberg, Igor Gurvich with Alla Dubrovskaia playing the violin. Sasha Mezheborskii appeared in later years. Second, the ensemble functioned all year round, traveling to other cities with several programs. Twice the group went toLeningradandRiga. I generally did not perform, only substituting if someone became ill.

Do you know anything about Purimspiels in other cities?

Purimspiels appeared inLeningradeven before us inMoscow. There, too, several groups were formed. We also had a pair of professional actors who put on plays. Our Purimspiel, however, was unique because it sparked the development of the Purimspiel as a phenomenon. We even acquired a tradition: the first Purimspiel was always performed in the southwest of the city at the home of Inna Moiseevna Badanova. It was the most dangerous performance because we didn’t know how the authorities would react to it. Even though they wouldn’t disperse it, during the first performance the police were always stationed below and there would be spats with the neighbors.

Once we performed a Purimspiel at the Litvaks’ apartment. In the course of the action, there was a scene in which Haman knocks on the door, Mordechai says, “Come in,” Haman knocks again, Mordechai repeats, “Come in,” and Haman: “Open, or else I’ll break open the door.” The Purimspiel would start and end with that same scene. And lo and behold, it’s the first scene, the second scene, and then the door bell rings. Everyone laughs. Zhanka Litvak opens the door─and it’s the police. Everyone thinks that the police are part of the performance and they laugh like crazy. But it really is the police, who have been summoned by the neighbors─you are bothering us, making noise. In short, we got away with it. I should add that the “actors” used to come to the performances with a change of underwear and a toothbrush, just in case. My authorship was carefully concealed until 1986, and in that year, Mika Chlenov came on stage and announced it festively.

Different times, Roza.

But we were not yet aware that times were different. Starting in 1984 I had a co-author─Gena Melikh. We tried to collaborate with professionals but it never worked out. How can a professional work with a group when the entire show is performed on a door removed from its hinge, there is no possibility of moving around, and, moreover, the actors are amateurs?

On the tenth anniversary of the Purimspiels, in 1986, we put on a jubilee performance that was a collection of the best of the Purimspiels. That was in March, and in May we were summoned and told to re-apply for an exit visa. They seemed to be saying that the issue was resolved. It was totally unexpected; no one had received exit visas yet. It was afterChernobyl. We arrived inIsraelin July 1986.

The second group that performed a Purimspiel in 1977 consisted of Aron Gurevich, Polina Ainbinder, Boria Chernobylskii, and others. When reading Ahashverus’ decree, Mordechai (Gurevich) held the newspaper Izvestiia in his hands and read the decree from it. Literally the day before, Lipavskii’s article had appeared in that newspaper, and the entire audience clearly understood the subtext. The group gave only one performance and didn’t continue. Aron Gurevich became an organizer of children’s Purimspiels. A year before the first Purimspiel, he also organized a choir in which Ainbinder’s sisters played an active role.

Zhenia, I said to Finkelberg, Purimspiel performances quickly spread in our milieu.

Yes, once there even was a festival of Purimspiels. Our performance was followed by that of Geizel and then of Mila Kaganova. It wasn’t even a competition but simply arranged for the audience’s convenience─why should they have to go here, there, and everywhere. In Geizel’s, they performed in kippot (yarmulke) and with great religious piety. Later on, the interesting group of Haim Briskman appeared but that was already a religious event─he was a student of Ilya Essas. We once did a Hanukah performance with Haim but it did not become a tradition.[9]

In the refusenik community, Purimspiels were merry and popular activities that were most in tune with the Jewish tradition of rejoicing, abandon, and abundant libations on this holiday. Thanks to the skill of the scriptwriters and actors, in the Purimspiels our own fate in a marvelous way became intertwined with ancient history in which the Jews emerged victorious against a powerful and cunning enemy. The celebration of Purim, like that of other Jewish holidays, spread to many cities and became part of the identity of the refusenik community.

Hebrew Week, March 5-11, 1979

Pavel Abramovich, the founder and editor-in-chief of the journal Our Hebrew, initiated the “Hebrew Week” inMoscow. The timing was not accidental. In1879 inParis, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda published an article, “A Burning Question,” that set the stage for the revival of modern Hebrew. The Hebrew Week thus marked the centennial celebration of the revival of the language. In addition, 1979 represented one hundred years since the birth of Feliks Lvovich Shapiro, the compiler of the official Hebrew-Russian dictionary.

It was decided to conduct the Hebrew Week at the time of Purim. Reports, concerts, and Purimspiels were prepared. Abramovich was universally liked and it was impossible to refuse him in anything.

How did the idea arise? I asked Abramovich.

In the newspaper I read about a Week of Kazakh Culture, then I glanced at a notice about another such Culture Week, and I started to think: why shouldn’t we have a “Week of Hebrew Culture”? I went to discuss the idea with Chlenov, who said it was a brilliant idea.[10]

As I recall, it was a large undertaking. Other people helped?

Of course, there was a lot of work to do─addresses, apartments, lecturers, notices. Volodia Prestin, Mika Chlenov, and Lenia Volvovskii got involved in the project.

How many apartments did you use?

About twenty.

How did it work?

Lectures were delivered, there were evenings of Hebrew song, and theatrical performances. On March 6, there was a Purimspiel. Improvised concerts frequently took place after the reports. In one apartment, the reports were given only in Hebrew. Do you remember? That was for you and Ulanovskii.

Yes, indeed. Ulanovskii gave something on grammar and I told about the history of the language.

In the second issue of the journal Our Hebrew, 40 out of 140 pages dealt with the Hebrew Week.

Serezha Lugovskii delivered a report about Hebrew’s place among the languages of the world and he also spoke about the modern revival of conversational Hebrew. A separate report, prepared and read by Ruth Okuneva, touched on Eliezer Ben-Yehuda’s activity. She livened up her speech with photographs and melodies of that time. Lia Feliksovna Prestin-Shapiro gave an outstanding report about her father, Feliks Shapiro. Aleksandr Bolshoi devoted his report to contemporary Israeli prose. Mark Lvovskii recited excerpts from his own work “Biblical History,” a transposition of the Bible into verse. There was considerable interest in Chlenov’s report on “Hebrew and Russian, a Millennium of Contiguity” and in an evening onJerusalemprepared by Leonid Volvovskii.

About a thousand people participated in the Hebrew Week.

Conclusion

On December 25,1979, aSoviet army column crossed the Soviet-Afghan border on a pontoon bridge over theAmu DaryaRiver. Two days later, a KGB Alpha unit stormed the presidential palace and carried out a bloody coup inAfghanistan. Afghan president Hafizullah Amin, his son, and all 200 presidential bodyguards were killed. Thus began the unexpected Soviet invasion ofAfghanistan.

Several months before the invasion, in June 1979, Leonid Brezhnev and Jimmy Carter made a major breakthrough in reducing international tension by signing in Vienna SALT-2, the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. The surprise Soviet invasion caused a genuine shock in the West. The achievements in détente of the past few years were blotted out in a moment and the Iron Curtain again descended on the borders of the Soviet bloc.

[1] Feliks Aronovich, interview to the author, June 3, 2007.

[2] Aba Taratuta, interview to the author, May 30, 2007

[3] Mikhail Beizer, interview to the author, April 25, 2007.

[4] Mikhail Nudler, interview to the author, May 18, 2006.

[5] Roza Finekelberg, interview to the author, March 30, 2005. Roza died young after a sudden illness in 2008.

[6] Roza Finkelberg, interview to the author, March 30, 2005.

[7] Leonid Volvovskii, interview to the author, April 4, 2006.

[8] Roza Finkelberg, interview to the author, May 30, 2006. [You interviewed her twice? See ft. 6]

[9] Evgenii Finkelberg, interview to the author, May 25, 2005.

[10] Pavel Abramovich, interview to the author, August 22, 2008.