The new round in the Cold War was clearly reflected in the Soviet regime’s attitude toward judicial and extra-judicial harassment of activists. Whereas in May 1979, on the eve of a planned summit,[1] Eduard Kuznetsov and Mark Dymshits were released early from prison,[2] followed shortly by the release of another five participants in the First Leningrad Trial, in 1980, the KGB subjected many activists to threatening warnings. If that didn’t suffice, the regime exerted additional pressure (detentions, searches, and new threats) on the activists and their families. The most implacable were arrested and imprisoned.

In August 1980, for the first time in seven years, the USSRbegan jamming Russian-language broadcasts of the Voice of America, BBC, and Deutsche Welle. On January 6, 1981, it was reported that Soviet authorities were returning packages sent to refuseniks from Israeland other countries.[3]

The ideological struggle against Zionism was intensified: anti-Zionist and antisemitic articles were published regularly in newspapers, books, and brochures around the country. Vladimir Mushinskii, whose duty in the Jewish movement involved monitoring anti-Zionist printed material in the USSR for fifteen years (from 1976 to 1991), calculated that, taking into account the provincial press, on the average throughout the country anti-Zionist and antisemitic articles appeared 24 times a day, an article per hour.[4]

The authorities also began to persecute forms of Jewish activity to which they had earlier turned a blind eye. Seminar leaders and Hebrew teachers were subject to harsh pressure. Professor Aleksandr Lerner was forced to close his cybernetics seminar: at the time that the seminar was scheduled to meet, policemen were placed in front of the entrance and prevented the participants from entering. The authorities subsequently demanded that Lerner and many other Moscowrefuseniks stop meeting visitors from abroad.[5]

Viktor Brailovskii, coordinator of the physics seminar, was arrested; afterwards, the same method was used as at Lerner’s home: policemen blocked seminar participants from entering the building.

Between August and September 1981, about ten key lecturers of semi-official Jewish seminars, including Irina Brailovskii, Aleksandr Lerner, Aleksandr Yoffe, Yakov Alpert, and Yulii Kosharovskii, were warned that they would be expelled fromMoscowif they continued to give lectures.

The regime would go after Hebrew teachers in earnest in 1984 when an underground network of Hebrew instruction set up byMoscowteachers in various cities would be partially uncovered. Even in the period from 1981 to 1982, however, there was considerable pressure on teachers and pupils. The dry chronicle of Jewish affairs reveals the following picture:

On October 15, 1981, the KGB and police conducted searches in the homes of Pavel Abramovich, Natalia Khasina, Yulii Kosharovskii, and Leonid Tesmenitskii, activists involved in teaching and spreading knowledge of the Hebrew language. Printed material, books, typewriters, tape recorders and tapes were confiscated. The searches were conducted in connection with the Shefer-Elchin case in Sverdlovsk.[6]

On October 23, 1981, massive pressure was exerted on Hebrew teachers. KGB departments in various cities summoned teachers and demanded that they stop teaching. Roald Zelichenok was brought to the KGB after a search in which they confiscated 40 books. The search was conducted in connection with the case of the Sverdlovskteacher Lev Shefer.[7]

On November 5, 1981, eighty Hebrew teachers in Moscowwere individually ordered to stop teaching. Some of them were under constant police surveillance.[8]

On November 8, the Leningrad KGB did not allow students studying Hebrew to enter the apartment of their teacher Yakov Rabinovich. Rabinovich was told to stop teaching or he would face arrest.[9]

On January 17, 1982, the Leningradrefusenik Grigorii Vasserman was beaten up by three unidentified individuals when he was returning home from a private Hebrew lesson.[10]

On February 11, 1982, several Moscowactivists were summoned to the KGB, police, or CPSU Central Committee and warned that thus must halt Hebrew studies.[11]

On February 12, 1982, policemen burst into the apartment of refusenik Mikhail Nekrasov during a lesson. They confiscated Hebrew textbooks, dictionaries, and cassettes and warned students to stop attending Hebrew classes and seminars. Nekrasov was told that he would lose his Moscowresidence permit if he did not stop teaching Hebrew.[12]

On June 11, 1982, the Moscow refusenik and Hebrew teacher Pavel Abramovich was summoned to the KGB for the fourth time in the course of a month (May 14 and 21, and June 3), despite the fact that he had stopped teaching on May 21. He was handed an additional list of demands: [stop] producing samizdat, transmitting information to the West, and meeting with undesirable foreigners. He was warned that teaching Hebrew was regarded as disseminating bourgeois nationalist propaganda.[13]

On January 22, 1982, the Moscowpolice dispersed a group that gathered for a Hebrew lesson at the apartment of Irina Shchegoleva.[14]

From my own experience, I can add that real life was even more complicated because not all harassment was publicized abroad or reported in Jewish chronicles. I led seven groups of students and a teachers’ seminar, that is, a Hebrew lesson every day and on Sunday─ a Hebrew group in the morning and a seminar in the evening. Although I had received many warnings to stop teaching, I decided not to give in. From the middle of 1981, the regime switched from words to deeds. I would be detained on the way to a lesson practically every week. At first it seemed entirely harmless. A policeman at the metro exit would demand to see my documents, take my passport, and suggest that I follow him to the police station where “they will explain everything.” At the police station they usually did not explain anything, would detain me for three hours in some room or cell, and then release me. Sometimes they would say that something had happened in the neighborhood (a robbery, brawl, apartment break-in, and so forth), and I resembled one of the suspects, but the check showed that it wasn’t I.

Sometimes at the police station, plainclothesmen (KGB agents) would try to speak with me nicely, if not to say heart to heart: “Well, how many times do we have to warn you? You are walking along a very slippery path. We will not permit you to disseminate bourgeois propaganda under the guise of language teaching. Look at what happened to so-and-so.” In time, the tone of the conversation became more and more threatening: “We would have gotten rid of you long ago, but your institute categorically will not consent to that. Cease your Zionist activity or we’ll arrest you. You are already teetering on the very brink.” Then they started phoning my home and speaking to my wife. “Tell your husband that there are people who want to break his arms and legs if he leaves the house this evening.”

From time to time, policemen accompanied by plainclothesmen would appear at my lessons: “the neighbors reported that there is an anti-Soviet gathering here at your place,” and they would confiscate textbooks and tape recorders, check everyone’s documents, and leave.

They next started to record the names of those in attendance. For students at institutes of higher education that could be dangerous as they could be expelled “for unbecoming behavior and nationalistic interests.” I had to suggest that they switch to less prominent teachers.

Later on, in the fall of 1982, I was detained and a short, difficult conversation ensued: “You are not reacting to our signals, we shall not detain you any longer, one more half-step….” The words in such a case are not that important. During the lengthy period of my refusal, I had learned to distinguish between a well-performed bluff and a real threat. This time I sensed that they were not bluffing, that my reserve of freedom had been used up.

Naturally, I did not say anything to them, but I decided that the Hebrew teachers’ seminar would have to be given to someone else; fortunately, there were plenty of capable teachers. Although that would be perceived as a certain concession on my part, it might enable the seminar to continue. The physicists, for example, continued to meet at other apartments and their seminar, although with a smaller group, continued to operate.

I had already begun transferring my students to other teachers as it had become too dangerous to continue classes at my place. I proposed that two talented teachers─Yulii Edelshtein and Lev Gorodetskii─run the seminar. They agreed and suggested holding two seminars instead of one─a dibur in Hebrew under Edelshtein’s direction and a didactic seminar led by Gorodetskii.

Developments indicated that the KGB had received much greater freedom to suppress any opposition to the regime. Arrests and prison terms became significantly more frequent phenomena. “Whereas in the second half of the 1970s, twenty-one Jewish activists were sentenced to long prison terms in the USSR, in the first half of the 1980s the number reached 40.”[15]

The regime struck at the dissidents first. Without a trial or investigation (although he had demanded a trial), Andrei Sakharov, the world-renowned leader of the democratic movement, was exiled to Gorky. In 1980, thirty-three members of the Helsinkigroups were arrested. Toward the end of the year only three members of the Moscow Helsinki group were at liberty─Sakharov’s wife Elena Bonner, the mathematician Naum Meiman, and the lawyer and defender of human rights, Sofia Kalistratova. They held on for another two years. “On September 8, 1982, Elena Bonner declared at a Moscowpress conference that the majority of the Helsinkigroup members had been arrested and further work had become impossible, and she announced the dissolution of the Moscow Helsinki group.”[16] From the fall of 1979 until the summer of 1980, 150 dissidents representing a broad spectrum of nationalists and religious activists were arrested and tried. Any independent group with a civil or legal inclination became the target of harassments.[17]

The political wing of Jewish activists was crushed in the course of the Shcharansky trial from 1977 to 1978. Vladimir Slepak and Ida Nudel were exiled. Dina Beilina received an exit visa and the patriarch of the movement, Aleksandr Lerner, already weak from the constant stress and hedged in all around by the regime, was forced to close his seminar. It was made very clear to Lerner that he should have been in Shcharansky’s place and it would not be difficult to correct that in the future. Lerner’s wife, Judith Abramovna, died in January 1981 while in refusal, a tragic event that was mourned by all the refuseniks. She suffered from high blood pressure, and the stressful refusenik life undoubtedly shortened her life.

Clearly aware of the focal points of Jewish activity, the KGB planned to strike a blow precisely at them, but before the Olympics, the regime was not in a hurry to reveal its plans. Arrests occurred during that time but mainly in the provinces.

Moisei Tonkonogii fromOdessawas arrested on February 11, 1980 on a charge of parasitism. After two months he was sentenced to a year in a general regime forced labor camp. He had previously received numerous refusals and been threatened with arrest because of his activity.

The construction engineer Moshe Zats was arrested inZhitomiralso in 1980. Zats had applied for an exit visa toIsraeltwo years earlier, been refused, and started a struggle to emigrate. He was charged with anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda and sentenced to two years in strict regime camps.

Aleksandr Magidovich was arrested in Tulain May 1980.[18] His family had immigrated to Israel, leaving him without any relatives in the USSR. In 1973, the forty-nine year old radio engineer had received a refusal on grounds of secrecy and from that time on, he had not stopped fighting for the right to leave while working as a postman. At first he was placed in a judicial psychiatric institution for a few months and subsequently was sentenced to a two and a half year term for “deliberately disseminating false rumors defaming the Soviet state order.”[19]

Two men from Leningrad were arrested for refusing to serve in the army: Igor, the son of Soviet chess champion Viktor Korchnoi, who had defected to the West (in November 1979), and the refusenik Grigorii Geishis (1980) After applying for an exit visa in 1978, Geishis was expelled from his institute and immediately called up to the army. The two men were sentenced to two years of general regime camps.

The regime conducted more significant trials with a large international resonance after the Olympics.

Moscow

Viktor Brailovskii was the only one remaining from the group of scientists who had organized the first scientific seminar in 1972 and initiated the publication of the samizdat journal Jews in the USSR. Despite official pressure, he continued with his activities and became widely known in the West. At the time, Western scientists who were advocating a complete scientific boycott of the Soviet Union in protest against Sakharov’s exile toGorky constantly discussed that topic with refusenik scientists and members of the physics seminar. BecauseGorky was a closed city and foreigners thus could not visit Sakharov, they maintained a link with him via the seminar. Even though the scientists in the seminar did not support a boycott, the situation was a sore point for the authorities.

Viktor Brailovskii explained the scientists’ position to me:

We thought that it would be more useful if foreign scientists came to our seminar and constantly raised the issue of Sakharov at meetings with the Soviet leadership. Moreover, in 1980 we started planning a fourth international seminar on collective phenomena that would take place in 1981. That work required considerable coordination, clarifications, and meetings. We began preparing in earnest and we thought that important scientists, including Nobel laureates, would attend as they had in the past. I myself sensed that those preparations became yet another source of irritation to the regime. In other words, instead of an external boycott, we considered that a more effective path would be to stir things up domestically.

What happened to the journal? [Jews in the USSR]

Although we did not have a strict schedule, we usually tried to put out an issue every three months but that became impossible after the Afghan invasion. We still managed to produce the final issue in 1980. The situation then began to deteriorate rapidly.

Did you announce that you had halted publication of the journal?

No. It simply became very difficult technically to support the entire process of work with authors, typists, and distributors. And it was too dangerous.

There were three searches at the Brailovskii’s apartment in the year and a half before his arrest in connection with: Igor Guberman’s case, the journal, and the scientific symposium. The last one was three months before his arrest. As usual, the KGB turned everything topsy-turvy and confiscated all samizdat and foreign material, including the scientific reports of the previous international symposium. Viktor was arrested on November 13, 1980 and sent to Butyrka prison.

The regime understood very well that this arrest was a signal, and it chose the date deliberately. Two days earlier was the opening of the Madrid Conference on compliance with the statutes of the Helsinki Accords. The regime thus made it clear that the refuseniks could not count on the West’s protection and that no Helsinki Act would help them.

Brailovskii was charged with slandering the Soviet social and state order and disseminating the journal Jews in the USSR. The case against the journal had been dragging on for many years, from 1974. There were no accused, only witnesses in that “case.” The impression was created that it existed as a way of reining in the publishers and authors. When a convenient moment appeared, however, the KGB struck. Viktor declared to the investigation that this was a blatantly political trial, falsified from start to finish, and he therefore refused to answer any of their questions. The trial took place from June 17-19, 1981 in the Moscow municipal court building. Brailovskii concluded his speech at the trial with the words: “I am not so naïve as to assume that my speech can somehow influence the course of the trial or its result. If, however, there are two people in this room for whom my conclusions are interesting and cogent, it is worth the effort. And, truly, there are two such people in the room.”[20]

On June 18, 1981, theMoscowmunicipal court sentenced Viktor Brailovskii to five years of exile. The Supreme Court of the RSFSR upheld the sentence. Brailovskii spent ten months in Butyrka prison during the investigation and appeal.

On the Sunday following her husband’s arrest, Ira, like her husband Viktor a brilliant scientist and editor of Jews in the USSR, invited the seminar participants to a session, as usual, in her apartment. Glancing out the window, she saw that two policemen were sending back each person who had come to the session. When she went downstairs and approached the policemen, they said that they didn’t have the slightest idea why they had received an order not to allow the seminar to take place. Nevertheless, they would stand at that spot the following Sunday and every Sunday after that. “Today is the first time in eight years that we missed a seminar,” Ira told Western correspondents.

Brailovskii’s arrest demonstrated that under the new conditions, no one was safe. Even quiet nonpolitical activity such as leading seminars, teaching Hebrew, or dealing with Jewish culture evoked a sharp response from the authorities.

On November 26, 1981, Boris Chernobylskii was arrested inMoscow. At the beginning of June, he had been detained on the street, kept for two days in the police station, and released with an order forbidding him to leave the city. After the November arrest, theMoscowmunicipal court sentenced him on December 9, 1981 to twelve months of general regime imprisonment “for resisting the police while performing their official duties.” He was also accused of striking a policeman.

In Leningradon November 6, 1982, Yosif Begun, the well-known veteranMoscowrefusenik and fighter for the revival of Jewish culture, was arrested for the third time. He was sent on a transport fromLeningradto the city ofVladimir, where he was placed in the notoriousVladimirinvestigative prison. He was charged with “agitation and propaganda with the goal of subverting the Soviet regime under the guise of struggling for Jewish culture and the right to study Hebrew.” For the first time it was blatantly demonstrated that the regime viewed Jewish culture and the struggle for it as anti-Soviet propaganda with the added goal of subverting the Soviet regime. A symbolic move in the regime’s battle to prevent the spread of Jewish culture, it exposed Begun to the threat of severe punishment. Previously, the authorities had preferred to punish those fighting for Jewish culture with fabricated charges of hooliganism, resistance to the police, parasitism, or other petty crimes. Begun himself had been arrested and imprisoned “for parasitism” in 1977. His second arrest─in 1978─was on a charge of violating the passport regime.

This was the first time that the real reason─disseminating Jewish culture and fighting for its legalization─was spelled out. On October 12, 1983, Begun was sentenced to seven years of imprisonment and five years of exile, the maximum term under Article 70.

Wow! That was really harsh, Yosif, I said to Begun.

Honestly speaking, I myself did not expect it. After so many years of activity, Brailovskii had been given five years of exile and here…. It’s true that for me this was already the third round. The repressions against kulturniki reflected the regime’s fear of Jewish culture. In its eyes, culture was the most dangerous thing of all; it represented subversion of the foundations. TheSoviet Union, after all, was multinational. If the Jews were allowed to develop their culture, then others would demand the same. The regime needed a thunderous trial, to be followed by other trials, against Hebrew teachers and others. I think that national culture was more dangerous for them than Zionism because Zionism was diminished by emigration whereas culture was nurtured from within and had an all-encompassing nature, and the ideas could spread to other national minorities.

Begun’s sentence was the harshest one given to a Jewish activist from the time of Shcharansky’s trial. He did not, however, have to serve the entire term as he was released in 1987 along with other Jewish activists and dissidents.

The trial of the noted dissident Vladimir Albrekht took place inMoscowon December 15, 1983. Albrekht’s manuscript “How to behave at interrogations” was very popular among dissidents, refuseniks, and Jewish activists. He participated with pleasure in the work of refusenik legal seminars, delivered lectures, and was available for consultations. He was sentenced to three years of imprisonment for “anti-Soviet agitation.”

Moshe Abramov, a former student at the Moscowyeshiva, was arrested in Samarkandon December 19, 1983 for teaching Torah to children, an officially prohibited activity. He was not charged, however, with teaching minors but with malicious hooliganism, and on January 24, 1984, he was sentenced to three years of imprisonment.[21]

Kiev

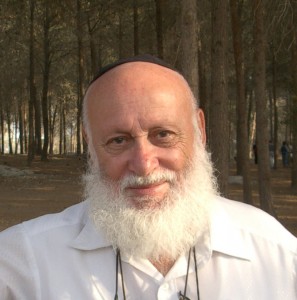

Kim Fridman, a widely known veteran refusenik who led an educational seminar and taught Hebrew, was arrested inKievon March 18, 1981. At first he was charged with resisting the police and held for ten days; he was then transferred to an investigative prison and on May 18 was sentenced to a year of imprisonment for “a parasitic way of life.”How many years had you already been a refusenik? I asked him.

Nine.

Did they try to force you to find work before your arrest?

I didn’t need to be forced; I was working, incidentally, in the same place as Volodia Kislik, as a book binder. In December 1980, however, they ordered that I be fired retroactively from September. As a result, there was a gap in my work record that they utilized to pressure me.

I recall that you led an active life in refusal.

Absolutely. I used to go to Babii Yar with my entire family, I taught, and led a seminar, which was held at my apartment. Even my schoolgirl daughter had a “tail” following her. I would celebrate Purim and other holidays, travel toMoscow, and I used to come to you.

On March 19, 1981, the longtime refusenik Vladimir Kislik was arrested inKiev. A scientist, organizer, and one of the leaders of scientific and legal seminars, he was widely known in refusenik circles and abroad. Kislik applied for an exit visa in October 1973, received a refusal on grounds of secrecy, and from that time on tried to work at various non-specialized jobs. He was arrested numerous times, imprisoned for fifteen days, and searches were conducted in his apartment; he was also taken off a train and beaten.

Volodia is an athletic fellow with a strong physique. He was beaten fiercely for the first time after he received a refusal, for prophylactic reasons, so to speak. It happened during his work as a night guard at a boat house. The second time it almost came to a genuine slaughter when he went with friends to honor the memory of the Jews slain at Babii Yar. In June 1976, he was beaten again, and warned to halt his scientific seminar. In 1977, an article in the newspaper Vechernii Kiev accused him of transmitting classified material on nuclear physics abroad.[22] In March 1980, Kislik was threatened with arrest if he did not stop meeting with his refusenik friends or foreign guests. During theMoscow Olympic games he was placed─no more and no less─in a psychiatric clinic.

This time Kislik was arrested when he returning from celebrating Purim. He was charged with “malicious hooliganism” for allegedly attacking a woman and beating a man who tried to help her. The witnesses at the trial were KGB agents who had been tailing him. During the investigation and at the trial, Kislik refused to take part in the court examination, declaring that he did not want to participate in a totally fabricated case. On May 26 he was sentenced to three years of corrective labor. He served his term in the camps of theDonetskregion ofUkraine. During that time he suffered two heart attacks.

What upset them so much about you, Volodia? I asked Kislik.

It was just life in refusal; after all, you know about that. The Ukrainian KGB officer explained to me that I was refused because ofRussia. I was working at an atomic center in the Urals and they had no influence onRussiawhereas they could resolve issues more simply with regard to those who were sitting because ofUkraine. I therefore remained in refusal all the time. In the middle of November 1979, literally in one day, the possibility of leaving was closed off. Even some of those who had already received permission but did not yet have the exit visa had the permission taken away: they were told it was a mistake. A huge mass of refuseniks was thus created at once─thousands of families.

What did the refuseniks do, what seminars were there?

First of all, there were several Hebrew ulpans. Kim Fridman, Lev Elbert, Zhenia Yutt, and a few others were the teachers. There were historical, scientific, and legal seminars; I consider the legal one as the main one.

Did you organize the scientific seminar?

Yes, at the end of 1974.

Who led the historical seminar?

Kim Fridman and I were the oldest refuseniks and we organized it. The others changed all the time. We had some kind of literature and we prepared reports. A more educated public, including those who were not refuseniks, came to the scientific seminar.

Who dealt with the legal seminar?

I organized it; it was a subject that interested me. People were completely ignorant: they didn’t know the laws or how to talk to the authorities.

What happened after the Olympics?

The authorities began to tighten the screws. Refuseniks were dismissed]; they had already sold their apartments in anticipation of leaving and now no one would give them a job. Told that they would never leave, this mass of people dashed about without knowing what to do. I was working as hard as I could. We needed to explain to people how to act and how to organize into groups. We needed to find leaders who would take charge of the groups. It was a difficult time. People had already used up all their resources for their departure. Something needed to be done for us and them. Later I found out that the secretary of the central committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine gave an order, first, to accept people for jobs but at the lowest positions and second, to pressure them.

Was there some help from abroad?

Visitors brought jeans and things like that. Foreigners mailed packages that local people sold in the special stores and they distributed the money. I organized a group of three or four people who dealt with that. But it was impossible for such a large number of people to survive on that alone.

I heard that you were sent to a psychiatric institution more than once.

During an investigation in 1981, I was taken toKharkovfor psychiatric evaluation because in the first psychiatric institution they wrote that I had some kind of syndrome. InKharkovI spent about two weeks in a psychiatric institution. There they said that I was healthy and I could be tried.

On May 16, 1981, Stanislav Zubko, a refusenik scientist with an advanced degree in chemistry, was arrested in Kiev. He was charged with the illegal possession of arms and drugs that, according to Zubko, were planted in his apartment by the KGB. In the two years after he submitted documents for an exit visa, he spent a total of 75 days in detention for so-called hooliganism, the popular Kievpunishment for activism. On May 23, 1981, the Kievmunicipal court sentenced him to four years of corrective labor in a general regime camp. He had a difficult time, having to serve out the full term: possession of narcotics does not fall under the option of an amnesty or dispatch to “khimiya”[usually work at a Soviet construction project under less difficult conditions than at a labor camp]. An athletic, strong fellow, he was severely beaten at the transit camp. He is convinced that it was also a sheer provocation. “Zubko appeared in 1979,”recalled Vladimir Kislik. “He was one of my helpers in conducting the seminars. When I was arrested, he worked actively to defend me, traveled to Moscow, and raised a ruckus. He, too, was then arrested and imprisoned after me.”[23]

On May 25, 1983, Lev Elbert, aKievrefusenik and Hebrew teacher, was sentenced to a year of imprisonment for “evading army service.” Elbert knew English very well, was an excellent Hebrew teacher, and had good connections among refuseniks and with people abroad. It was a rare instance when a refusenik was not arrested before his trial. He was forbidden to leave the city. We shall examine the peculiarities of his case later.

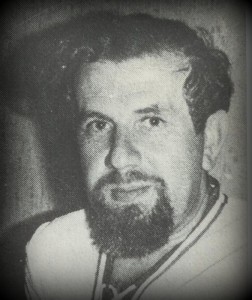

Kharkov

On August 28, 1981 Aleksandr Paritskii was arrested inKharkov. The coordinator of a scientific seminar and director of an independent Jewish refusenik university, he was a significant figure for theKharkovrefusenik community. His activities in the six years before his arrest encompassed the struggle for aliya, forging links with foreigners, attempting to erect a monument at a site of the mass murder of Kharkov Jews, and organizing protest demonstrations; throughout this time he was harassed by a campaign against the “slanderer,” “hooliganizing dissident,” “petty intriguer,” and “speculator” Paritskii in the Kharkov press. He was threatened, his apartment was searched, and he was removed from a train and reprimanded by a “court of colleagues.” Seeing that he did not intend to give up the fight, the regime charged him with slandering the Soviet social and state order.A “home university” for refuseniks’ children was opened inKharkovin September 1980.

When was the scientific seminar organized? I asked Paritskii.

In1979. Inthe summer of 1979 they stopped issuing exit visas inKharkov. InMoscowandLeningradthe situation was still favorable and even inKievit was possible to leave but here and inOdessaemigration came to a halt. A thousand people wound up in refusal. Afraid of running out of time, they had made preparations in advance of their departure and sold their belongings. Many scientists and engineers wound up in refusal and thus the need for a seminar arose.

How often did you meet and how long did the seminar function?

We met approximately once a month. As inMoscow, the participants took turns reporting on the topics of their former scientific research. In addition to the scientific seminar, we had one on culture. We would get together on the eve of holidays and give lectures on the upcoming holiday.

The seminar continued until my arrest in 1981. After that, both the seminar and the university were closed down.

On November 13, the municipal court sentenced Paritskii to three years of general regime corrective labor camps. He served his time in the same camps in Vydrino where the Muscovite Yulii Edelshtein was later sent.

Kishinev

On April 22, 1980, Leonid (Aryeh) Volvovskii was arrested in Kishinev. “Sometime at the beginning of 1980,”recalls Aron Munblit, a Hebrew teacher and leader of a seminar in Kishinev, “the Hebrew teacher Leonid Volvovskii came to us. I prepared several groups for his arrival. He is a talented teacher and knew how to make every lesson a holiday. However, this lasted no longer than ten days.”[24] “Yes,” adds Volvovskii, “I was picked up right at the lesson. The conditions in prison were awful─rats and filth, but after a few days, the prisoners obeyed only my orders.”[25] Later it turned out that the pretext for his arrest was the absence of a residence permit. They tried to charge him under the article for “vagrancy” but that aroused such a wave of protests that he was released after a month.

On May 30, 1981, Osip Lokshin and Vladimir Tsukerman were arrested during a protest march near the Kishinev OVIR for organizing the march. “We submitted documents for an exit visa a year earlier, after Afghanistan,” Lokshin told me, “and we received a refusal on the grounds of a ‘lack of a sufficiently close relative.’ Aron Munblit and I were active participants in the Kishinevlegal seminar.” Tsukerman was fighting for an exit visa from 1975. Anaval officer and ranking sportsman, he was a graduate of the Kaliningradhigher naval academy. For a year his parents refused to give their consent to his departure. His documents were accepted only in 1976. “Before that protest march, I went alone to demonstrate in front of OVIR,” Vladimirtold me. “I received 15 days, and that was already the sixth or seventh such arrest. Before that I had been removed from a plane and detained and removed from a train and detained. Before the march, I was summoned to the office of the Moldavian interior minister, who said: ‘If you will cancel the demonstration, you and another three or four people will receive visas but if you will go to the demonstration, we’ll arrest you.’ I decided to go anyway with everyone else. They wouldn’t have gone without me.”[26]

The Moldavian Supreme Court in an assize session that was held from September 22 to 25, 1981 tried and sentenced both of them to three years of general regime imprisonment for “the organization and active participation in a group action that disturbed public order.”

Leningrad

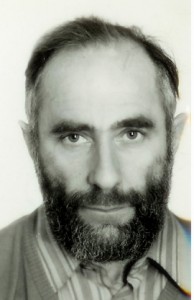

The refusenik scientist Evgenii Lein was arrested in Leningradon May 17, 1981. He was fired from his job on the day he submitted his documents in the summer of 1978, and he received a refusal two months later because his “departure did not serve state interests.” The head of the Leningrad OVIR told him: “You and your wife both have Ph.D. degrees. It is not profitable for us to supply qualified workers to other countries. That would contradict the Soviet policy in the Middle East.”[27]An active participant in the Leningrad seminar on Jewish history and culture, Lein analyzed numerous cases of refusal and transmitted his findings to the West. His daughter Nehama was subsequently beaten up on the street. It later became clear that it was done “in order to teach someone a lesson.”[28]On May 17, the seminar was held at Grigorii Vasserman’s one room apartment. After twenty minutes, the police forced their way in. They began to photograph the participants and search the briefcases left in the kitchen. When Lein asked the senior person in the group to present his identity card, he ordered: “Take him away.” He was dragged past a row of local guards to the stairwell and then to a bus on the street. They started to interrogate him directly in the bus. The colonel directing the operation told the interrogator: “Give him Article 191, section 2”─resisting authorities with violence against the police. It carries a punishment from one to five years. [29] On the same day three other seminar participants were detained and held for fifteen days.

On August 5, 1981 theLeningradmunicipal court sentenced Lein to two years of corrective work in “khimiya” in the small Siberian city ofChernogorsk,6000 kilometersfromLeningrad.

Sverdlovsk

Vladimir Elchin and Lev Shefer were arrested on September 21,1981 inSverdlovskon charges of disseminating anti-Soviet literature. Trying to discover the sources of this literature, the authorities carried out searches in the apartments of leading refuseniks inMoscow,Leningrad,Novosibirsk, andVilnius. Shefer wrote poetry, songs, and brochures on various topics. Starting in 1981, he and Elchin would mail material for studying Hebrew and Jewish history and culture. The original charge (Article 190 “prime” with a possible punishment of three years) did not include the intention to subvert the Soviet regime; consequently, however, the authorities decided to intensify the punishment and “intention” appeared in the charge. The article of the charge was accordingly changed to Article 70 (up to seven years of imprisonment and five years of exile). TheSverdlovskmunicipal court sentenced Elchin and Shefer to five years of loss of freedom.

Novosibirsk

The activist Feliks Kochubievskii was arrested in September 1982 inNovosibirsk. He was famous among refuseniks for his excellently written samizdat work on legal issues of refusal. He sent many letters to official Soviet bodies and helped other people. Kochubievskii was charged with the “systematic distribution of deliberate fabrications defaming the Soviet social and state order.” On December 10, 1982, he was sentenced to thirty months of imprisonment in general regime labor camps. He served his term in prisons in Novosibirsk, Sverdlovskand Permand also in a camp in Solikamsk.[30]

You seriously studied and utilized Soviet legislation, I commented to Feliks.

My interest in the topic, as you understand, was born of necessity. I was not part of the first generation of applicants fromNovosibirsk, but it so happened that our apartment became the center of the aliya struggle. People would come and ask how to live and what to do. I thus decided to write an article on that topic: I sat in the library studying for about three months and wrote under the impression of Albrekht’s work. The resulting brochure, which was composed in a completely Soviet style, was entitled “A Juridical Manual on the Legal Foundations of Departure from theSoviet Unionto Permanent Residence in Other States.”

As I recall, you were a master of “Soviet style” in other initiatives as well.

We set up a Novosibirsk Association for the Friendship of Peoples, USSR-Israel in 1979. Everything would have been all right, but we very quickly selected the secretary of the regional Communist Party committee as the honorary chairman of the society. He didn’t say anything, but I was interrogated at the KGB, and the deputy KGB director shook his head and said: “You did this in vain, in vain.” But what could we do? In the constitution it speaks of the friendship of peoples, it’s written down in the party program, and he was a deputy of the Supreme Soviet and a member of the CPSU Central Committee. Well, who else could be selected as honorary chairman? I said, “What should be corrected? If he had written that he renounced it, but he didn’t write that. You can’t say that he’s not worthy.” It thus just remained suspended.

Did your sons leave before you?

They left as a result of my appeal to Muhammed Ali (Cassius Clay), the world boxing champion. That was in 1978. I read in the newspaper Za rubezhom [Russ. for overseas] that Brezhnev received Muhammed Ali, who had organized the “League of the Struggle for a Worthy Human Existence.” It was reported there that Brezhnev gave Ali permission to shoot a film in the Soviet Union in which he planned to film interviews with a policeman, a housewife, and so forth, in various places, including Siberia. I wrote to Muhammed Ali that I welcomed his desire to do that and I invited him to Novosibirsk: if he wanted to film an interview with policemen, then he could do so at the Novosibirsk OVIR, where human rights are violated, in particular, the right to emigrate to other countries, which they deny to people without the necessary legal foundations. I gave an example of two musicians, one a violinist and the other a pianist, saying that they couldn’t possess any secret information just as my two sons couldn’t possess any secrets─one of whom recently finished the institute and the other was a student. I sent the letter to theU.S. embassy with a request to convey it to Mohammed Ali; a copy, of course, went to the executive committee of the regional Soviet. I kept the original at home. I wrote that, as I was not sure that the mail works well, I sent several copies so don’t be surprised if several letters arrive. I didn’t send the original; let the KGB look for it. A big fuss ensued. I was summoned to the regional committee and told: “Hush, hush. We are now resolving your issue. Don’t write anywhere anymore.” They gave exit visas to my sons and both musicians. In that case, I thus managed to obtain visas for my sons after half a year in refusal.

Did you think up some kind of variations for other people?

There were a lot of people around me and they would come for advice. I would give advice and, at first, I even used to write something for them but then I stopped. My wife said: “Don’t do that! You are recommending moves that you would do in their place. But, after that, they make the next move in their own way.” I thought about it and, really, she was right.

Were you tried on Article 190?

Probably, and also on Article 70, but I am, however, the recipient of an award and an inventor, one of the founders of theInstituteofAutomation, and an honored worker, and so forth. They took all this into consideration and recorded it in the sentence.

Was it difficult in prison?

In general, I survived well enough. The criminals respect individuality, and Article 190 “prime” was respected by them.

Over a period of little more than two years, up until Yurii Andropov’s accession to power in November 1982, seventeen anti-Zionist trials were conducted in theUSSR. The KGB was clearly demonstrating that the rules of the game were changing: henceforth, they would arrest the rebellious ones rather than send them out of the country─“either you will behave quietly or you’ll sit in prison.” The refuseniks who received warnings were told that emigration would be halted in the near future and they would spend the rest of their life in theUSSR. There would be no more “rewards” for activism in the form of exit visas; arrested activists would also not be allowed to leave after their release.

Arrests were customarily accompanied by attacks in the media at all levels: local, regional, or all-union. Other methods were also used. For example, theKharkovauthorities declared at a local meeting that a Zionist movement had been exposed inKharkovand its members would soon be put on trial. The Kharkov KGB demanded that Polina Paritskii, wife of Aleksandr Paritskii, cease her activity in support of her arrested husband or else she, too, faced possible arrest. A KGB officer showed documents to her parents testifying to the opening of a legal case to take her children from her. Their daughter Dorina was told the same thing in school. Many people were subjected to interrogations. Numerous searches were conducted not only in the location of the activist’s arrest but also in other cities. TheHelsinkiprocess, which had engendered so many hopes in the second half of the 1970s, turned into an arena of harsh verbal clashes, which, however, had little effect on the fate of the Jews detained behind the Iron Curtain

Andropov further intensified the persecution of Jewish activists and of Hebrew teachers in particular.

[1] A summit meeting between Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev and U.S. President Jimmy Carter was planned for early June 1979. The START-2 agreement on limiting strategic arms, in which theUSSR was keenly interested, was to be signed at the meeting. TheUSSR also received a promise from the American administration that it would work for the repeal of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment.

[2] Convicted in the Leningrad Hijacking Trial, Kuznetsov and Dymshits were released as part of a multilateral exchange. They arrived inNew York on the eve of the most important annual demonstration of solidarity with Soviet Jewry─”Solidarity Sunday”─ at which they spoke before an audience of over a hundred thousand people.

[3] Soviet Jewish Affairs, “Chronicle of Events” 11, no. 2 (1981): 98.

[4] For a small fee the organization “Mosgorspravka” offered press monitoring on a particular topic. Mushinskii subscribed to materials on Zionism andIsrael and regularly received bundles of publications. Using the accepted methodology of the journalism faculty ofMoscowStateUniversity, he calculated the average number of publications around the country.

[5] Soviet Jewish Affairs, “Chronicle of Events” 11, no. 3 (1981): 98.

[6] Ibid., p. 102.

[7] UCSJ Bulletin, “Alert,” October 23, 1981.

[8] Soviet Jewish Affairs, “Chronicle of Events” 12, no. 2, (1982): 86.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., p. 88.

[11] Ibid., p. 89.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., p. 97.

[14] Ibid., p. 102.

[15] Kratkaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia (Jerusalem, 1996), 8:282.

[16] Soviet Jewish Affairs, “Chronicle of Events”13, no. 1 (1983): 100.

[17] Gal Beckerman, When They Come for Us, We’ll be Gone, p. 435.

[18] Alert (news bulletin of the Union of Councils for Soviet Jewry) 4, no. 31 (August 28, 1980).

[19] Internet site “Remember and Save,” in Russian: http://www.soviet-jews-exodus.com/; in English: http://www.angelfire.com/sc3/soviet_jews_exodus/English/index.shtml

[20] “The Brailovsky Case,” AJC Institute of Human Relations,N.Y.,N.Y., April 1983.

[21] Soviet Jewish Affairs, “Chronicle of Events” 14, no. 2 (1984): 99.

[22] Vechernii Kiev, September 27, 1977. At the time, an attempt was made to attach Kislik’s case to Shcharansky’s “spy trial.”

[23] Vladimir Kislik, interview to the author, February 19, 2004.

[24] Aron Munblit, “Ten Years in Refusal, Like40 in the Desert (1977-1978),” ms. (in Russian).

[25] Leonid Volvovskii, interview to the author, April 4, 2006.

[26] Vladimir Tsukerman, interview to the author, May 12, 2009.

[27] Evgeny Lein, Lest We Forget: The Refuseniks’ Struggle and World Jewish Solidarity (Jerusalem, 1997), p. 67.

[28] Ibid., p. 75.

[29] Ibid., pp. 5-6.

[30] The site “Remember and Save.”

![Fridman[1] Kim Fridman](https://kosharovsky.wendemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Fridman1-214x300.jpg)

![Paritsky[1] Alexander Paritsky](https://kosharovsky.wendemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Paritsky1-225x300.jpg)

![Evgeni Lein[1] co rs Evgenii Lein, co](https://kosharovsky.wendemuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Evgeni-Lein1-co-rs-208x300.jpg)