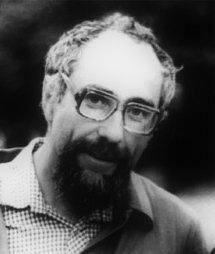

Yuli Kosharovsky’s Interview with Yosef Begun. Moscow, January 16, 2004.

A couple of days ago we celebrated the 15th anniversary of the renewal of Jewish culture in Russia which we counted from the first songs contests in Ovrazhki. Parties, meetings with old friends, conversations… Yosef and I are considered veterans there. We decided to celebrate this, also, by going to the Russian steam bath, as in the old days.

So, Moscow, Seliznevsky baths, steam room, a nice company, with Arkady Kruzhkov. We started spontaneously, as a continuation of the after-bath conversation. Yosef told us of his views on who should be considered a Zionist.

Yosef (YB): Zionists are those who joined the Jewish movement in 60-70-s, and their main wish was to emigrate from the Soviet Union to Israel. I remember quite well that I also joined them with a strong desire to leave. But it was clear that it was impossible to leave at once.

Yuli (YK): When did you first feel you were Jewish?

YB: Maybe when I first heard the word “kike” in my yard. I think many people experienced this. I do not remember anything Jewish at home, in the family. We lived in a working “proletarian” neighborhood of Moscow. It was even called “Proletarsky raiyon” and it was near the Likhachev [motor] plant, then Stalin [motor plant]. But when they started to call me “kike” in the yard, I understood that I was different from them, that I was Jewish. But I did not quite understand then what it meant.

YK: Did your parents want to make you altogether Russian?

YB: I do not think they wanted this.

YK: What did your parents do?

YB: My parents were quite a Jewish family. My father before the revolution was even a yeshiva-bohur. My mother mostly worked in simple blue-collar jobs. Like many other Jewish women, she was not educated. She worked at a factory to make her living.

YK: Where did she come from?

YB: She is from a [Jewish] village of Logoisk near Minsk. She left for Moscow to earn a living in 1929, and I believe this saved my life. She came from a patriarchal family with 14 children. Almost all my uncles, aunts, and cousins who stayed there, were killed. And I had a lucky ticket, I survived.

After a short interval, we continue our conversation in the cafeteria of the Siliznevsky baths.

YK: In short, you did not receive any Jewish education, but you already felt the “delights” of the Jewish existence.

YB: Yes, but my mother lived with such a Jewish feeling… Jewishness was respected in our family. My mother lived on memories of her childhood spent in a Jewish village.

YK: And the father?

YB: I do not remember my father, he did not survive the war. I was 9 when I lost him. I was growing up with my soul split: on the one hand I realized I was Jewish, and it was a burden for me. I did not want to be Jewish, I had so many complexes… I was, as they put it, a Jew hating himself. On the other hand, there was this atmosphere of reverence with regard to Jewishness in my family – it was very important for my mother. I was constantly in this split condition.

YK: Did you first feel a dissident or a Jew?

YB: First I started to feel Jewish, and I believe it was mainly caused by the feeling of hopelessness… I.e., if I had a chance to become a Russian, at some point I would become one. When I was still an ignoramus. At that time I did not want to be Jewish because I did not want to belong to the second class. This is what I felt. I was second-class, I was not like the others. This was a great humiliation for me, it was insulting, and feeling the hopelessness of it, I was quite ready… I remember that in my second and third grade in the beginning of the school year, the teacher performed a humiliating procedure: she wrote down the names of all children in the class journal, and when she pronounced a pupil’s name, he was supposed to stand up and say what his nationality was. I could not make myself say I was Jewish. I said I was Belorussian. Because my mother was from Belarus. I felt terribly ashamed. And for some time, it was written in the class journal against my name – “Belorussian”.

YK: From your stand today, how would you define the roots of this “shame”?

YB: I believe this is typical psychology of a young person who has complexes. I was a healthy boy, in the 30-s, we lived in poverty. My mother received a room in a shared apartment in a workers’ village of Dubrovka. This was big luck. I believe that today people who buy a country house for a million dollars do not feel that happy. You visited me there, right?

YK: Many times, and once you were arrested when I was there. Do you remember when it was?

YB: We had a yoga class, and then we were supposed to have a Purim celebration together.

It was on March 1st, 1977. This was my first arrest.

YK: And when was the trial?

YB: In June 1977. I was sentenced to 2 years in exile for parasitism. Every day in prison was counted as 3 days in exile. I spent in prison almost 4 months, and then it took almost 2 months to take me to the place of my exile. I was taken to Khabarovsk by train, then I was put on board a plane in handcuffs, and then they took me in a “voronok”, a special car for transporting prisoners, for another 2 days 650 km to Magadan in the Kolymsky territory. For some reason, they needed to place me in as remote and non-civilized place as possible. When I finally arrived there, it turned out that I only had 5.5 months more to serve. They were stupid! The second time I was arrested three months after my release from prison. I was released on March 17, 1978. And on May 17, I was arrested for violating the rules for registration in Moscow. Of course this was one of their tricks. The registration rules were aimed at prevention of registration in Moscow of dangerous criminals. So why this nonsense? When a police officer showed me a confidential decree of the Moscow government concerning the registration in Moscow of former prisoners, my article [of the Criminal Code] was added to this Decree manually. They just checked the box, and that’s it. I was denied registration in Moscow despite the fact that I had 2 minor children there.

YK: You have other children besides Borya.

YB: It was Borya who was the son of Alla Drugova. I adopted him. I have two children by the same name … He is now an ultra-religious person, he lives in Galillee and has 7 children.

[YK]: So you are saying that your second arrest was for violating registration rules. When was it?

YB: I was arrested on May 17, 1978, and I was very quickly convicted, within a month and a half.

YK: What was the sentence?

YB: I was sentenced to three years in exile. And I was sent to the same mine where I had served before. This time I spent more time there, 2 years and 3 months. I was released in August 1980.

YK: You then received a hero’s welcome at the railway station?

YB: No, this was after my third term.

YK: The third term was very serious. When was that?

YB: November 6, 1982. They were no doubt planning a major [anti-]Jewish case. They began building an extremely dangerous federal case of “agitation and propaganda with the purpose of undermining the Soviet regime” against me.

YK: Article 70.

YB: Yes, the 70th. And the case wasn’t worth a nickel. So they gathered my documents, where I wrote about the right of the Jews to study Hebrew, this… that…

YK: Remember, Dan Shapiro “framed” us on the TV, and that we sued channel, I think, 1? When was that?

YB: I remember, I remember… It was the day before I was first arrested. It was on January 21st 1977, soon after the bombing in the Moscow metro, and rumors were spreading, clearly instigated by the KGB, that this was the work of dissidents and Zionists. After this Academician Sakharov made a statement to the effect that the KGB provocation was aimed at destroying the human rights movement, and then on January 22nd Channel 1 aired a movie, the title of the movie was “Buyers of Souls”. It had two parts. I remember that movie well. Remember, there was also an Ulpan at the Taganka at Irina Abramovna Nekrasova’s.

YK: How can I forget, I used to teach there.

YB: Yes, but probably a bit later than the events described. In those days I taught Irina Abramovna Hebrew. We used to gather there, and there was a wonderful group of young people at that place, my son Misha and many of his friends.

Already at that time Avigdor (Vitya at the time) Eskind stood out amongst them. He was extraordinary. We became friends. I used him to help Sasha Temkin’s daughter – Marina. You surely remember that story. His wife didn’t want to leave the country. She submitted a request to take the child away from him and the police took the child from the father by force. When he went away in 1973, they sent the daughter to the pioneer camp “The Eagle” where they trained Komsomol leaders. From across the border Temkin begged them not to abandon his daughter, to help her and to take care of her. The daughter returned from “The Eagle” a different person, they re-made and re-educated her (apparently it’s not so hard to do this to a 15 year old child, she turned into such a good Soviet girl, lived with her mother, forgot about her dad. Her father was losing his mind, begged us to do something for his Marina. I sent Avigdor Eskind to her. He was an elegant boy, a musician, good looking, and they became friends. Well, once I was at the Nekrasov’s, teaching her, and there were other young people in the other room, and suddenly I hear a horrible cry: “Yosef! Yosef! Come over! They are talking about you on TV. It was on Channel 1, they were showing that movie at that very moment – “Buyers of Souls”. And there were you, me and Sharansky – you were on the screen right then – you and Sharansky with the athletes. After a while, on March 10th the Lipavsky article was published, and then on March 15th they put Sharansky in jail. And then, in this period we went to the court.

YK: We were walking, the three of us: Slepak, you and I. Afterwards, after several unlucky attempts at filing our complaint, we reached a judge, a former WWII Partisan who also refused to accept it. Afterwards Slepak left and the two of us were left there. They demanded that we stay away from each other. I’ll never forget how you drove the judge crazy, his face was covered with red spots.

YB: Yes, Yes…

YK: You were yelling at him: “Fascist!” He had already lost any kind of self control and he shouted- “I will call the police, I will send you to prison” and you replied: “You wouldn’t dare, because you’re a coward, you are even afraid to accept our statement, you are a fascist…” And I got the image of Begun, like an uncompromising fighter, quite dangerous to both sides…

YB: And do you remember the secretary’s comments?

YK: No.

YB: We filed a civilian lawsuit – “In defense of honor and dignity”. And when we left the judge’s chambers and found ourselves in the waiting room where the secretary sat, everyone there was excited. And the secretary, in an effort to calm us down a bit said: “What do you want of him, he’s criminal”. She meant to say that the judge works on criminal cases and not on civilian.

YK: And at the judge’s it was your fury against his. And you beat him. It was then that I realized what a dangerous person Yosef was, and I was also thinking, they will not forgive you for that…

YB: Against the Soviet regime that is. Be clear on that, or people might think…

YK: A man who loses his survival instinct in certain situations, complete lack of the limitations of danger, all fear is gone and he — fighting for his human dignity — just plows on. I had the pleasure of spending my first month-long term in a punishment cell in the beginning of 1971. Till then I was about the same as you in 77, “still undefeated”. But you didn’t change even after prison.

YB: The story of my first arrest is quite interesting. First, it was a TV movie. They wanted, of course, to frighten the Zionists. Do you remember what scenes were there?

YK: Ovrazhki…

YB: It was even before Ovrazhki. Do you remember how we rode to Krasnaya Pakhra, how we’ve hanged the Israeli flag on a birch-tree and how the cop later climbed to take it down? The cops back then weren’t yet that well trained, and they were nervous. We got onto a bus from Kaluzhskaya metro station, the last station that existed then. This was Luntz’s meadow. Don’t forget that at the end of ’76 there was a symposium on Jewish culture, Fain, Prestin and myself worked a lot on preparing that symposium. I remember that I wrote a big and serious report. And of course, the KGB… By the way, I can tell you a lot of interesting things, I have a theory on the KGB’s attitude to Jewish culture which I have not made public yet. There are two things. Why did they start arresting people in 81-83, including myself. My third trial, when they were really fighting me hard, was actually a trial of Jewish culture. While the first two were nothing special, the third one was against Jewish culture. And why didn’t they do it earlier, in the 70-s. Why didn’t they ever arrest a single religious teacher back then? I thought about it a lot, and I have my own theory about it.

YK: Nu…

YB: The matter is that the Jewish culture was like a bone in the throat for the authorities. They opposed it even more than the Jews did. And while the Jews opposed it because they were lazy, because they did not want to think, because they were assimilated, the authorities… You see, from their viewpoint, when certain “renegades” leave, it’s like “the woman off the cart, the horse is happy”. But culture it is already ideology, it means that the Jews start thinking about who they are, what’s going on with them, why they are in such a situation. The authorities were using “renegades” with whom they could not do anything as subsidiary coin for the détente, but at the same time they tried to keep the majority in the country. Thousands were leaving, but millions sat quietly. With what means they tried to keep these millions from doing anything. First, it’s refusals. One should have had to think it over several times, whether he should apply for an exit permit or not, because he never knew whether they would let him go. He knew that he will lose his job, that it will be hard for the family, and this stopped many people from applying. There were not so many people who were as enthusiastic as you and me. Most people did not want to ruin their lives.

1976, Cultural Symposium. It was like a thorn in the side for the authorities, but they were fighting it as they say “in white gloves”. They did not arrest or imprisoned a single person. But they labeled the symposium a Zionist provocation and they did not let it take place. They arrested me to punish for all that, because I gave them a handle against myself. I became a “conscientious parasite” – do you know my story of parasitism?

YK: Legalization of Hebrew teaching?

YB: Yes, i.e. if you arrest me, you admit that you do not consider Hebrew teaching as legitimate occupation. And they did not touch me for two years. They summoned me every two or three months to write a statement of parasitism, and that’s all, they did not arrest me. But after the symposium and that incident near the American Embassy when I came there with Fain, and they arrested us there…In 1977, the attitude to the Zionist movement changed dramatically. The bomb explosion in the Moscow metro, the movie “Buyers of Souls” – they became really nervous, and they wanted to show that Zionism, internal Zionism, is very dangerous. Therefore the movie shows contacts with foreigners, receiving money from abroad, anti-Soviet actions, these frames with Sharansky, Slepak embracing the sportsmen – this was presented as contacts with the Zionist centers abroad, and at that time it sounded pretty serious. Everyone understood that such things can be punished very strictly. This means that the authorities understood that people began to behave more freely, to “ungird”, and they decided to tighten the screws. It was 1977. And I fell victim to this.

YK: Their fears were mainly connected to the fact that Jews may leave or that they may serve as a detonator for more serious shocks? Their attitude to Jews was somewhat ambivalent.

YB: Yes, I agree with you. First, they were glad that the most active troublemakers like Voronel, leave. Such bright dissident personalities were attractive…

YK: Was Voronel a dissident personality or a Jewish one?

YB: He was of course a Jewish personality, but there were many other people there. In this way [the authorities] got rid of explosive elements, and they were happy with this. The others were held at bay and intimidated; they were shown who is the boss. Now, there was the Sharansky trial, and they lost it as well, but it was planned as such an intimidating trial aimed against all kinds of Zionist actions, with the CIA in the picture, espionage – a typical KGB plot which they were often acting out. But they still did not start an offensive against the Jewish culture because they can always kick away, and the others can be held at a safe distance that will not allow them to cross the borders of the allowed area. Then they arrested Slepak and Ida Nudel – in 1978. Well, you cannot deny that they were actually asking for it, hanging posters in the Gorky Street. And one should admit that they were punished quite mildly – Slepak was sentenced to 5 years of exile. At the time when people were sentenced to 7 years of strict regime camps for less serious crimes, for instance, for keeping Solzhenitsyn writings at home, it was not too bad. And Ida Nudel as well – if I am not mistaken, she traveled to the place of her exile alone [not under escort].

YK: It seems to me that they did not arrest her before the trial as a preventive measure.

YB: Yes, I believe she was arrested right there in the courtroom, I do not remember it exactly now.

YK: I will double-check.

YB: Then the 80-s came. Everything changed. The wind of freedom was blowing from Europe, the events in Poland, Afghanistan (1979), the Soviets were stuck there, the cold war. The emigration was stopped, and an interesting situation emerged. The Jewish refuseniks, a group of activists, one can say you were a major leader, and Begun was constantly around, and others. Look at Brailovsky, for example. And Brailovsky was immediately arrested. By the way, this is an interesting phenomenon, Brailovsky was the first to be arrested for publishing the magazine “Jews in the USSR”. In the summer of 1980.

YK: In 1980, I organized the second inter-city seminar of Hebrew teachers.

YB: This is when you were arrested for 15 days.

YK: There were representatives from 8 towns there. You can say that we have occupied Koktebel, about 300 people came there.

YB: So what, what is 15 days? They were still turning a blind eye on it. Children play, so let them play a little. But then it became more serious, you see. They arrested Brailovsky. The next case was mine. They had a lot of material for the case, but they had already had it for a long time, they just did not want to use it before.

YK: If you always spoke to them in the same manner you used in that conversation with the judge, I believe they should have arrested you several years earlier.

YB: No, there were other considerations. When the investigator, a colonel, interrogated me he said “[Your actions] fall under Article 70 [of the Criminal Code]. And I said, “Mr. Colonel, you must be wrong, it cannot be Article 70, maybe you meant Article 190?” Because Article 190 is slander and Article 70 is already sabotage of the Soviet power. He says, no, my dear man, yours is Article 70. And they start building a case [for this article]. Begun wrote an article entitled “Traditions of Anti-Semitic Propaganda Disguised as Anti-Zionist Propaganda” as early as in 1974. They stored this article till 1982 and presented it to me as a dangerous anti-Soviet declaration. The refuseniks kept quiet and not one was acting. There were no demonstrations either in 1981, or in 1982 or in 1983. They all understood what it could lead to in these days. Many people stopped learning Hebrew. And in this situation when emigration was non-existent, there was cold war, and stagnation and disorder reigned in the country, the aged Soviet leaders started dying one after another, and the Jewish culture became the element that preserved the Jewry and called it to action, it demanded elementary freedoms and cultural autonomy guaranteed by the Constitution, and it was intolerable for them.

YK: Well, they had Birobidjan for legitimization. It was a nice pretext. Did they have Ukrainian schools in Moscow? No, they did not, although there was a significant Ukrainian Diaspora.

YB: Well yes, I live in Moscow and I have the right to have my Jewish center in Moscow and all that. And then repressions against cultural activists reflected their fear of the Jewish culture because culture was more dangerous to them than all the rest. Our good Soviet citizen does not want to leave the country. And the “renegades”, let them leave. Independent culture is sabotage of the foundations.

YK: Where is sabotage?

YB: The country is multi-national. If Jews receive something, the others may demand this, too.

YK: I.e., Jews in their traditional role of a detonator of greater changes.

YB: Yes. And therefore they should be suppressed. I believe they were preparing a serious trial, like those planned a short time before Stalin’s death.

YK: They could not choose you for this.

YB: No, why? They did choose me, and there could be others after me.

YK: They knew that they cannot break you. They needed someone at your level, but of Dan Shapiro type.

YB: They wanted a big trial followed by trials of Hebrew teachers, but then Gorbachev came to power, and it was all over.

YK: Who was the ruler when you were arrested?

YB: Oh, this is interesting. When I was arrested, Brezhnev died. I was arrested on November 6, and Brezhnev was seen at the November 7th demonstration, and I believe he died on November 8. I was sure that I will be released immediately. Brezhnev was replaced by Andropov.

YB: I want to ask you a question. Why didn’t they ever arrest a single religious activist? Neither Essas, nor Rozenstein or others, but they arrested Brailovsky, Begun, Kholmyansky.

YK: Because religion had not chance to seize the masses.

YB: Oh, you are right. This is the reason. It is because of this. Religion is locked up in the synagogue. And when a person demands Hebrew, freedom for the press, contacts with his state, this they could not stand. And this is my theory: culture was more dangerous than Zionism, because it undermined from within, while Zionism was swept away by the emigration. It was also dangerous because Zionism had a local character, and culture was universal, and had good chances to spread to other ethnic minorities.