Fascist propaganda depicted communism as a Jewish invention and Jewish ideology; the fascists persecuted their own communists and portrayed the Soviet regime as under complete Jewish control, associations that Stalin undertook considerable efforts to discredit abroad. The historian Shmuel Ettinger notes that “in the early 1930s, because of the acute shortage of educated people and specialists, anti-Semitism was not a very acute social problem, but a new, quite intense antisemitic campaign began in 1936-37 when the first signs of Stalin’s rapprochement with Hitler appeared.”[1] The firing of Foreign Minister Litvinov was an additional signal that was appreciated by the Nazis.[2]

The Jews, who had been the embodiment of the old Bolshevik tradition of internationalism, were now accused of conducting espionage on behalf of foreign states. Russian nationalism and Panslavism replaced internationalism.

The so-called Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of non-aggression between Germany and the USSR was signed on August 23,1939 inMoscow along with a secret protocol that divided up spheres of influence and territorial interests. In accordance with this pact, extensive areas of eastern Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Bessarabia, Bukovina, and Transcarpathia were annexed to the Soviet Union. Another two million Jews were thus added to the 3,020,000 already residing in the USSR according to the 1939 census.

The Jews of the annexed territories spoke Yiddish and possessed a developed national consciousness. An active Zionist movement that was still operating in that part of Europe included future Israeli leaders such as Menachem Begin and the leader of the Haganah, Moshe Kleinbaum (Sneh).

The Jewish population of the former Polish territories welcomed Soviet troops as rescuers from the Nazi invasion, whose horrors they had learned about from many refugees. “In these areas Jewish communities, organizations, educational institutions, and scientific establishments continued to operate for some time but all parties were immediately dissolved, Hebrew was banned and school programs were changed. Tens of thousands of ‘unreliable elements’ were arrested and exiled to Siberia or Kazakhstan.”[3]

The Zionists encountered many hardships in Soviet labor camps but ironically the Bolsheviks thus unintentionally saved them from extermination by the Nazis. Some of the Zionists survived the harsh conditions and eventually made their way to Israel, for example, the Beitarists Boris Edelman (in 1971) and Eliezer Shulman (in 1976). The Beitar leader Menachem Begin founded the Herut [freedom] Party, which came to power in Israel in 1977 and Begin himself headed the Jewish state for many years.

During World War II the enlightened West remained largely indifferent to the Jews’ fate and abandoned them to the mortal danger facing them. One could even say that it betrayed them. One after another the enlightened countries of the West refused to take in the refugees who had escaped the Nazi regime on the eve of the war, and the British in effect barred them completely from Palestine. The Allies then watched aloofly as the Nazi regime carried out the annihilation of the Jewish population. Archival documents indicate that Western political leaders were aware of what was occurring but could not find a few planes to bomb the machines of total human destruction although they were begged to do so. The Allies consciously acted as they did because they considered that openly aiding the Jews could fan antisemitic agitation in their own countries and thus undermine their war efforts (Hitler had declared on many occasions that the World War was a struggle against “international Jewry”).

After the war, information about the Holocaust was not publicized immediately. Europe lay in ruins with millions of displaced persons and universal suffering. But when the story of the senseless, attempted total inhuman annihilation of an entire people became public knowledge, it shook the civilized world.

The Holocaust left a deep, festering wound in the Jewish national consciousness that cried out and demanded with each destroyed life, each final gasp: Enough! Enough of being a plaything in others’ hands! Let us take our fate into our own hands! The Jewish world swore: “Never again” and mobilized all its energy to restore Jewish statehood; shocked mankind gave it the mandate.

The Jews of the Soviet Union had a somewhat special attitude toward the Holocaust. The majority lived in the western part of the country and were a hundred percent mobilized. About a quarter of a million perished at the front and over 250,000 received medals and awards. “Soviet Jews felt like participants in the victory over the Nazis. They not only experienced the terrible losses but also felt that with their own hands they had killed the “monster.” They returned from the war with the feeling that they had accomplished something great….and in this they differed from their western brethren.”[4]

One must view the striking contrast between the Soviet Union’s Middle East policy from 1946-48 and its harsh policy toward its own Jewish population in the context of the global postwar confrontation between the former coalition allies. Stalin’s postwar Middle East policy was designed to drive Great Britain out of this strategically important region and, as much as possible, to supplant it. This goal determined Soviet support for the Jews’ struggle against the British in Palestine for their national independence. Had Arab national liberation movements existed at the time, the USSR would have supported them as it did later when the British left Palestine.

There is considerable evidence concerning the jealous concern of the upper-level Soviet leadership with regard to the Palestine’s Jewish leaders interest in Soviet Jewry. Soviet officials incessantly reminded them of the delicacy of this issue and its ability to influence Soviet support for the creation of an independent Jewish state.

The Soviet Union’s demonstrated support of Israel, however, gave many Soviet Jews the impression that the country’s leadership would welcome their demonstration of solidarity with Israel. The wounds of the Holocaust and the postwar antisemitism in combination with the Soviet Union’s favorable attitude toward the Jews of Palestine encouraged the growth of pro-emigration sentiments. The USSR did not object to the departure to Palestine of East European Jews who had wound up on Soviet territory during the course of the Second World War, but Soviet Jews were another matter.

Soviet domestic policy was based on the principles of total control, subordination, and the suppression of anything evoking suspicions of disloyalty. Jews, with their worldwide diaspora, struggle for the revival of national independence, and inclination toward internationalism had long ago evoked such suspicions, which were intensified as the result of a series of political and social processes.

As the enthusiasm for a worldwide proletarian revolution declined and the idea headed toward the dust heap of history, there was a movement away from the principles of internationalism, which the Jews had most noticeably championed. The new ideology of great power chauvinism labeled the Jews rootless cosmopolitans who worshipped the West. The Jews had relatives abroad and they were patently represented among the U.S intellectual and business elite. Jewish charitable organizations willingly helped their brethren abroad. It was thus easy to accuse Soviet Jews of insufficient patriotism, of suspicious contacts, and of cosmopolitanism. The ruling elite succeeded in convincing the populace to regard the Jews as a fifth column of hostile western influence. This created an atmosphere of permissibility of hatred towards the Jews that was successfully exploited by all kinds of rogues and careerists.

The creation of the State of Israel evoked rejoicing among many Soviet Jews. On May 14, 1948, the date of the proclamation of the state, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, which had been formed to support the Soviet war effort, sent a congratulatory telegram to Israeli President Chaim Weizmann; The Moscow Jewish community sent a similar telegram. Many people, including students in institutions of higher learning and army officers, wanted to fight on Israel’s side. They went to the military commissions, the Foreign Ministry of the USSR, and OVIR (visa office), requesting permission to travel to Israel in order to fight against the henchmen of British imperialism. Some appealed directly to Stalin with such requests and later suffered as a result.

“Colonel David Dragunskii of the armored tank forces, twice a Hero of the Soviet Union and in the 1970s notorious as the chairman of the Anti-Zionist Committee of the Soviet Public, visited the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee twice in 1948 and offered to form a special Jewish division for dispatch to the Middle East.”[5] “Rumors persistently circulated among the Jews that after the USSR’s official recognition of Israel, all Soviet Jews would automatically receive the right to emigrate there. Allusions were made to Lenin, who permitted Finns and Poles to go to their historical homelands when those countries gained independence after the October Revolution…. The residents of the town of Zhmerinka (over 500 people), for example, applied to immigrate to Israel as an entire community.”[6]

Some people, in violation of the legislative act of June 9, 1947 prohibiting direct contacts with foreigners, tried to turn to Israeli representatives. Many proposed that the Anti-Fascist Committee extend aid to Israel and begin collecting funds for buying it arms. Various underground Zionist youth groups strove to leave for Israel. In Zhmerinka, Ukraine near Vinnitsa, for instance, after its liberation from Nazi occupation in 1944, there was a group called Eynikeyt (Unity) that engaged in Jewish self-defense. One of the group’s leaders, Meir Gelfond, became one of the leaders of the Zionist movement in the 1960s-early 1970s. In Moscow another group included Roman Brakhtman, Mikhail Margulis, and Vitalii Svechinskii, who along with Gelfond became one of the Zionist leaders.

The visit by Golda Meir, the Israeli ambassador to the USSR, to Moscow’s Choral Synagogue on the holiday of Rosh Hashana on October 4, 1948 evoked a powerful demonstration of solidarity with Israel. In the very center of Moscow, two hundred meters from the headquarters of the Central Committee of the CPSU, a rejoicing crowd of 50,000 people welcomed the Israeli delegation ─ religious and secular, soldiers, officers, students, engineers, old people, youth and children borne high on their parents’ shoulders. When Golda emerged, someone shouted in Hebrew: “Am Yisrael hai” (the Jewish nation lives). She stopped for a moment and said in Yiddish, “Thank you for remaining Jews.” A nervous tremor passed through the crowd. She was received like the messiah; some fell into ecstasy and kissed the hem of her clothing.

A little over a week later, on Yom Kippur (October 13) a massive display of solidarity with the ambassador and with Israel again took place. Moscow had not witnessed anything like it for many years, for over a generation. “It was the sole unsanctioned gathering in the Stalinist Soviet Union…. It was not simply a show of sympathy but a demonstration of complete, absolute solidarity on the part of the Jews, who had experienced the Holocaust, the war against Nazism, and were victorious in this war.”[7]

This demonstration of solidarity was widely publicized in Israel and the West but not in the Soviet Union. Many perceived it as an expression of Soviet Jews’ desire to immigrate to Israel, which the Israeli leadership hoped for and which more and more aroused the dissatisfaction of the Soviet leadership. Golda Meir’s request to permit repatriation encountered an icy “NO.”

The Black Years of Soviet Jewry

Difficult times ensued for Soviet Jews. The period from the second half of 1948 until March 1953 is justly termed the “black years” of Soviet Jewry. It was a period of harsh confrontation between East and West. An additional factor was the pathological changes in the personality of the “Leader,” who toward the end of his life showed an increasingly paranoid suspiciousness. Although changes did not occur immediately in foreign policy, it became clear that an “iron curtain” had been lowered between Israel and Soviet Jews and between the USSR’s domestic and foreign “Jewish” policy.

By September 1948 Jews who had placed their names on lists of those eager to fight for Israel’s independence were already wending their way to forced labor camps. “Thousands of Jews were arrested from 1948-53 on charges of Zionist activity (Jewish bourgeois nationalism).”[8]

Rumors circulated that Golda Meir at first believed so firmly in the Soviet authorities’ benign disposition and in Stalin’s personal goodwill that she gave Foreign Minister Molotov the lists of all the people who had turned to the Israeli delegation for help in immigrating to Israel. The KGB allegedly utilized these lists. Although these rumors persisted for many years, they have not been officially confirmed.

“At the end of 1948 members of the Eynikeyt group were arrested in Zhmerinka, Kiev, Leningrad, and other cities…. Twelve people were arrested, of whom only nine were genuine members of the group. After an investigation that lasted over five months, a special commission sentenced them to lengthy terms of imprisonment from 8-25 years.”[9] Among them was Meir Gelfond, a leader of the group.

From 1947-1951 hundreds of Jews were arrested and received lengthy sentences (10-25 years) for attempts to cross the Soviet border illegally in order to reach Israel or for aiding such attempts. The group comprising Brakhtman, Margulis, and Svechinskii also planned an illegal departure and were arrested in 1950. Each received a ten year sentence. Zionists from the period of Israel’s rebirth met in the camps with Zionist veterans from the revolutionary period.

In the article, “How the Jews of Silence Began to Speak,” Svechinskii wrote:

Zionism of the Soviet period was implemented by the people of the 1920s, whose moral maturity held them back from participating in Russian revolutionary competitions. All their energy was directed at the Exodus. Some of them remained in Russia, fulfilling their duty to their political parties, whose leaders immigrated to Palestine. Gradually, under the influence of socialist ideology, any recollection of these unknown soldiers of resistance completely disappeared.

These Zionist fighters, who engaged in “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda,” tried to ensure that their brethren remain part of the Jewish people. Almost all of them went to prisons and labor camps and perished there.

Only at the end of the 1940s, like the phoenix, post-classical Zionism arose from the ashes, unaware of its previous existence….

There in the Soviet torture chambers occurred the meeting of new “Jewish bourgeois nationalists” with some surviving veterans of classical Zionism. Thus appeared the fragile thread that restored the broken link of time….

The idea of the Exodus did not perish. Its weak flame, like a candle’s flame did not let hope be extinguished. The existence of Israel provided a vital stimulus to the Prisoners of Zion; it preserved them and they preserved it. And this armor stood up to the test.”[10]

For what were you arrested? I asked Vitalii Svechinskii.

We wanted to flee to Israel. The War of Independence was being waged there; we were nineteen years old. We thought of crossing the border in the south, across the Charokh River; it’s a whole story.

Did you admit your guilt?

The three of us were arrested and we admitted our guilt. But the authorities wanted to expand the circle….they needed to arrest around ten to twelve, but they came up against a wall. We were threatened and subjected to petty physiological discomforts. Then we were threatened with the torture prison at Sukhanovo, which was truly terrible.

What was your sentence?

Not bad, a “tenner.” We were lucky.

How did it go?

It depended. At the beginning it was very difficult. The winter of 1951-52 was harsh, the camp regime was awful, and the main thing ─ there was no grub. I was assigned to earth digging work, which is very strenuous. Even people with good health reached the end of their tether there. I was a gymnast with third level ranking, didn’t complain about health, but I very quickly declined. My organism required sustenance but there wasn’t any. We had to work an exhausting ten-hour day in the frost and there was no place to take shelter. I very quickly became a “goner.” Jews saved me. I had a camp father, Natan Zabara, a Yiddish writer. And there was also a fellow, Irma Druker, God bless his memory. They didn’t do the general hard work; in the convoy garrison they served in the kitchen, chopped wood, paved, in general, they performed light service work. The cook would bring them something to eat from the kitchen. Natan would collect cereal in a jar and bring it to the zone. That was very dangerous because people were frisked before entering the zone, but he did it so artfully he was not caught. Thus every evening I was able to receive a portion of cereal and this saved me.

Was the second year easier?

It was easier; we learned somewhat how to survive, how to behave; we “sniffed things out” as they say in camp. We learned how to endure both hunger and cold, which was already a lot. Then Fimka Spivakovskii and I went to the camp director’s weekly reception hours and told him that Fimka graduated from the economics faculty of Kharkov University and could do something besides striking the earth and that I was a third-year architectural student and could work in that field. This camp happened to have a planning “sharaska” [prison research institute]. Two or three weeks later I was summoned and told that I would be transferred there. At first I worked the night shift. It was difficult because my fingers couldn’t bend to hold the pencil but with time I got the knack of drafting. I designed various officers’ homes and a residential settlement and this work was, of course, a lot better.

On November 20, 1948 the Politburo adopted a secret resolution “On the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee” that called for dissolving the committee immediately, closing its printed organ and seizing all its files insofar as it had allegedly turned into a center of anti-Soviet propaganda and was regularly supplying foreign intelligence organs with anti-Soviet information.

All documents were brought to the Lubianka and became evidence in the criminal case opened against the committee. The same thing happened in the editorial office of the newspaper Eynikeyt, whose last edition was published on November 20, 1948. At Stalin’s order the chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, the actor Solomon Mikhoels, was murdered in Minsk on January 12, 1948. However at the time Stalin was playing his Middle East card and in order not to stir up feelings abroad, the government organized a lavish state funeral. At the beginning of 1949 dozens of Jewish social and cultural figures were arrested. On the night of August 12, 1952 , twenty-four Jewish writers, intellectuals, and artists were shot, including Solomon Lozovskii, the former director of the Soviet information agency Sovinformbiuro; the writer Yitzhak Fefer (although he cooperated with the MGB and the investigation); the historian Iosif Iuzefovich; the director of the Botkin Hospital in Moscow, Boris Shimeliovich; the poets Leib Kvitko, Perets Markish, David Bergelson, and David Hofshteyn; the actor Veniamin Zuskin; the journalist Lev Talmi; the editors Emiliia Teumin and Il’ia Vatenberg; and the translator Haika Vatenberg-Ostrovskaia.[11] One of the accused, Solomon Berkman, became ill and died in hospital. On that night Jewish culture in the Soviet Union was decapitated.

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was the sole Jewish public organization that had extensive international connections. During the period of the investigation, Molotov’s Jewish wife Polina Zhemchuzhina was arrested, “Jewish writers’ organizations in Moscow, Kiev, and Minsk were disbanded, Jewish publishing enterprises were closed, and many Jewish writers and journalists were arrested…. The liquidation of Jewish cultural establishments and arrests of Jewish writers and cultural workers occurred throughout the country.”[12]

In January 1949 another major antisemitic campaign was initiated ─ against “rootless cosmopolitans.” An article in the party organ Pravda on January 28, 1949, “About an Anti-patriotic Group of Theater Critics,” launched the campaign. The co-authors of the article were major party figures ─ Georgii Malenkov, Petr Pospelov, and Dmitrii Shepilov but the “scale of the propaganda, the elevated accusatory pathos, and the inquisitorial spirit told the reader of Stalin’s invisible presence.”[13]

“The term ‘rootless cosmopolitan’ became a synonym of Jewishness; an accusation of possessing those ideological vices was sufficient to fire writers and journalists from editorial boards and publishing houses. The Pravda article, supplemented by a secret letter from the party Central Committee to party organizations in the republics and regions…was perceived as a general directive to destroy Jewish cultural centers, close Jewish theaters and Jewish publishing houses, clubs, and creative unions that applied even to Birobidzhan (Jewish autonomous district).”[14] Other papers seized upon the Pravda article, and the atmosphere of a witch hunt quickly spread, accompanied by a large number of arrests.

The antisemitic wave rapidly moved from the ideological arena to scientific and economic spheres. Alexander Lerner, an important scientist and witness of those events who later become one of the leaders of the Zionist movement of the 1970s, wrote: “For the sly, unprincipled, anti-Semitic careerist, it was a happy hunting ground. All he needed to do was denounce a colleague and his ‘courageous exposure’ would earn him a promotion. Phony patriots grabbed this opportunity to wipe out successful Jews and take their places as dean of a school, department head in a research institute, or manager of a publishing house.”[15] “The expulsion of the Jews,” continued Lerner, “from all branches of science, including the exact one, was merciless without regard for the harm done to science, to its practice, and to the prestige of the Soviet Union…. Anyone could be charged with cosmopolitanism if he was cited by foreign scientists, mentioned in Western science or neglected to proclaim the priority of Russia and the Soviets in all world cultural achievements.”[16]

Places that dawdled in expelling the Jews were visited by a commission from the party district or city committee or another organization, after which organizational conclusions were reached ─ the director himself was punished or fired.

Whereas the case against the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was designed to sever the link between Soviet and world Jewry and the link with the West as a whole as well as to decapitate Jewish culture, the campaign against “rootless” cosmopolitans declared, in effect, that the entire Jewish population of the Soviet Union was a fifth column of Zionist and Western influence.

The culmination of the public antisemitic campaign was the “Doctors’ Plot,” the “murderers in white doctors’ robes” that was fabricated as a offshoot of the case against the Anti-Fascist Committee and then turned into a major independent production that was supposed to create a pogromist atmosphere in the country and enable Stalin to solve the Jewish Question in any form that was acceptable to him, including a total purge of Jews from the central cities and their mass expulsion beyond the Ural Mountains.

Of the thirty-seven people arrested in the Doctors’ Plot, twenty-seven were Jews. A new wave of arrests was accompanied by a propaganda campaign. Medical personnel, particularly Jews, were harassed throughout the country. Cultivated on a well-fertilized field; the monstrous antisemitic campaign created an atmosphere that seemed pregnant with the threat of a pogrom inspired from above. Reprisals against people of Jewish appearance began in public places.

After Stalin suffered a stroke on first of March 1953, Pravda, as if on command, within a day stopped printing material about the “enemies of the people.” Other newspapers gradually followed suit. Investigations continued by inertia for another three weeks and then stopped.

Stalin’s death may have saved the Jews from mass deportations but the black years of antisemitic agony left a deep festering wound in peoples’ souls. The many years of stress crippled a considerable segment of older generation Jews with a pathological dread of the all-powerful totalitarian state and fear of everything that was national-Jewish. The same events, however, opened the eyes of some of the youth, tempered their souls and their character, and aroused national sentiments. Many of them later joined the ranks of the Zionist movement in the USSR.

Although the majority of Jews were able to return to their former workplaces after the end of the press campaign, the situation could no longer be the same. Closing the Doctors’ Plot case did not stop the spread of antisemitism in the USSR. Soviet obsession with security considerations, paranoid fear of “enemies,” and the perception of Jews as hostile agents with dangerous links with the West were all retained in full measure even after Stalin’s death although in a more moderate form. State antisemitism remained up until the fall of the Soviet Union, changing only in form and tone.

From the very first day the young Jewish state encountered a host of difficulties: war with its Arab neighbors; the ingathering of the Jews who had survived the Holocaust; and the establishment of a state with all its institutions. At the time the Soviet Union was on Israel’s side (more accurately, it was against Great Britain), extending substantial military and political support. At the same time, however, it reacted with extreme irritation to any Israeli attempts to establish contacts with Soviet Jews. Taking this situation into consideration, the Israeli leadership acted very cautiously in anything that concerned the Jewish problem in the Soviet Union.

Moreover, to a certain degree the West was not aware of the true situation there. Information about Mikhoels’ murder and the reprisal against Jewish writers and public figures ─ the members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee ─ took a few years to reach the West. The cosmopolitan campaign, which was also directed against the Jews, at first did not make a serious impression on Jewish leaders in the West.

The watershed in Israeli policy toward the Soviet Union and the lost Jews behind the Iron Curtain was the Slansky Trial in Czechoslovakia in November 1952 and the subsequent Doctors’ Plot campaign in the Soviet Union in January 1953. Ben-Gurion concluded that Israel needed a special intelligence agency capable of contacting Jews behind the Iron Curtain, analyzing the situation there, and of making recommendations to the country’s political leadership. The agency that was created in 1952 received the name Nativ (path); it was subordinated directly to the prime minister. The name Nativ was known only to a small circle of the initiated. In the Hebrew press it was referred to as “Lishkat Hakesher” (the Liaison Bureau) or simply as the Bureau. It was a small organization headed by Shaul Avigur, former head of the Mossad le-aliya bet organization that dealt with illegal immigration to Palestine before the founding of the State. Most of the staff had also worked for that organization.

First contacts in the USSR were received through their Israeli relatives. Graduates of Jewish schools and former members of youth and Zionist organizations were also of interest for Nativ.

…Avigur’s office gave the legation [of Israel in the USSR] staff precise instructions regarding contacts with Soviet Jews: whom it was advisable to meet, how meetings were to be arranged and what it was permissible and desirable to talk about. Similar instructions were issued to all Israelis who visited the USSR: they were to frequent places where Jews were likely to be, making certain, however, that their conversations with local Jews did not veer into any subjects that might be interpreted as anti-Soviet; in order to ensure that neither they nor their local contacts came under the slightest suspicion of criticizing the Soviet regime, it would be best to stay away from the subject entirely. Nor were the Israelis to discuss the situation of Soviet Jewry. They were to restrict conversations to Israel’s everyday life, goals, and achievements, and even to discuss its problems and failures.[17]

The local Jews, who were unaware of the secret instructions and the reason for them, were often amazed by the conduct of Nativ workers. The terrible antisemitic campaigns in the Soviet Union had just recently ended, but state antisemitism continued to flourish; the local Jews were seething, but the Israelis were unwilling to discuss these topics! Moreover, the Israelis stopped contacting the people who insisted on bringing up those matters again and again. Some activists even received the false impression that the Israelis were deaf to their problems and not prepared to help them.

Nehemiah Levanon, who later replaced Avigur, recounted:

In the first month we equipped ourselves with local radio receivers, which were not of a very high quality, in order to check the level of reception of Israeli radio stations. When we had accumulated sufficient data, we conveyed the appropriate recommendations to the Tel Aviv office…. The quality of the transmissions improved. We mobilized Russian-speaking editors and announcers, which was not easy because there had not been any immigrants from Russia for decades. Through our contacts, we informed local Jews of the network of radio broadcasts and the most suitable wavelengths for reception in accordance with the location.[18]

In the summer of 1955 when the Thaw was at its height and there was a noticeable shift from confrontation to dialogue in international relations, the KGB decided to strike a blow at Nativ. In the beginning of July searches were carried out simultaneously in several homes and arrests followed. One of the activists, Eliahu Guberman, was arrested during a meeting with Nehemia Levanon in a private apartment of Levin. Guberman (1895-1980), who had been a member of the Tseirey Tsion [Zionist youth] movement (from 1913-1918), enjoyed Levanon’s complete trust. He had already served a six-month prison term for Zionist activity in 1926. This time he received a ten-year sentence after a big trial in Moscow. At the time his wife received two years and several other people received terms from two to ten years. Released after five years, in 1966 Guberman obtained an exit visa for Israel.

The KGB understood very well that Nativ’s activity was not anti-Soviet. They were, apparently, conducting prophylactic measures in order to stop the spread of the “Zionist disease” and avert an epidemic.

Three Nativ workers, including Levanon, were asked to leave the Soviet Union in August 1955. From that time on the Soviet Union occasionally expelled Israeli embassy workers who engaged in cultivating contacts with Soviet Jews.

Nativ established a subdivision called Bar for mobilizing public opinion and lobbying political bodies in the West. It was supposed to develop connections in the power structures and facilitate the functioning of effective lobbying mechanisms; create awareness in the Jewish and non-Jewish world of the difficult situation of Soviet Jewry; and coordinate the struggle of various forces demanding that the Soviet regime permit free immigration to Israel. Nehemia Levanon, who had just been expelled from the Soviet Union for “activity incompatible with the status of a diplomat,” was appointed head of Bar.

Nativ’s new approach was tested in 1955-56. Several occurrences facilitated this: Nikita Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Twentieth Party Congress in February 1956; the Hungarian Revolution in June 1956; the Polish political crisis in October 1956); the Sinai Campaign (October 1956); and the anti-Israel campaign in the Soviet press. Considerable pressure was exerted on the Soviet leadership. The issue of Soviet Jewry was raised at the level of governments, political parties, and delegations, including delegations of communist parties from other countries. It was raised both by delegations visiting the Soviet Union and during Soviet delegations’ visits to the West. The free press widely publicized the questions and answers at such meetings.[19]

In 1956 information reached the West about the destruction of the flower of Jewish culture in Yiddish. “A courageous Jew succeeded in conveying detailed information to the Israeli embassy about the execution in August 1952 of over twenty Jewish writers and poets, members of the Anti-Fascist Committee and the names of the victims. This information was confirmed by additional sources that the embassy was able to contact.”[20] The repercussions of the four-year old tragedy could be tremendous.

Nehemiah Levanon recalled:

A plan of action was worked out. At the end of February Leon Crystal, an experienced and respected journalist from a solid New York Yiddish newspaper, was supposed to travel to the Soviet Union…. The Soviets were probably interested in his visit, assuming that on his return he would write about the substantial improvement in the Jews’ situation (at that time several booklets in Yiddish had been published in the Soviet Union and permission had been given to open a Yeshiva for training a small number of rabbis). I met him in Paris on his way to the Soviet Union. He was thoroughly shaken up. It turned out that he not only recognized the names of the writers and their most important works, but he also had gotten to know many of them personally during their visits to New York as delegates of the Anti-Fascist Committee. I explained our view of the problem to him and suggested that he publish the information in a way that made it appear as if he had received this information during his visit. I instructed him how to behave and with whom to meet. [21]

“Upon returning from the USSR early in March 1956, Crystal told a press conference that an ‘unimpeachable source’ had given him not only the facts but even the very date of the writers’ executions: 12 August 1952. The writers’ closest relatives had recently been given this information by the prosecutor general in Moscow who expressed the Soviet government’s ‘profound regret’ and promised that the victims would be rehabilitated posthumously.”[22] In articles on this topic Crystal emphasized that the Jewish writers’ terrible fate was significant not only with regard to the past but also was directly related to the present and future of three million Soviet Jews. It was therefore most important to reveal the truth to the world and to begin a struggle for their liberation.[23]

Crystal’s article stimulated a whole series of items in the leftist and even the communist press (including an article in the Warsaw Folks-shtime), pointing out to leftist intellectuals the Soviet regime’s discriminatory policies.[24] The article’s appearance in the press not long before the publication in the West of Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Twentieth Party Congress reinforced the effect of the disclosure of the crimes of Stalin and his regime. Bar achieved its first significant victory.[25]

Bar was supposed to rely on the support of Israeli embassies. In three major centers it was decided to mobilize local circles and create public organizations that would coordinate their activity with Bar. These organizations could take upon themselves the work of translating, editing, publishing, and disseminating material. The center for French was Paris, for English ─ London [26] and for Americans – New-York

Nativ workers understood very well that they would have to fight against a powerful system of disinformation. “The truth was our sole reliable weapon against this well-oiled propaganda machine,” recalls Levanon.[27] “Any exaggerations, inaccuracies, or deceit ─ the usual methods of Soviet propaganda ─ could turn into a humiliating failure for us. We could defeat them only with facts presented as they really were. This approach was also preferable because during the years of the propagandistic Cold War, the western public had become suspicious of material about the Soviet bloc. If we sounded like the usual anti-Soviet propaganda, we probably would not attract serious attention.”[28]

Bar continually expanded its activity, setting up divisions in many countries and conducting systematic informational-lobbying activity. This work continued for 35 years, until the complete removal of restrictions on Soviet Jewish emigration in 1990.

From the middle of the 1960s Nativ devoted considerable efforts to establishing an academic research center and it succeeded in attracting the prominent historians Ben-Tsion Dinur and Israel Halperin. A group of researchers gradually formed around them, with whose help the noted Centre for the Documentation of East European Jewry was founded at the Hebrew University. Many prominent academics took part in the work of the Centre. The Israel Historical Society, in whose framework the Centre functioned, was an independent organization with its own budget.

The collections of documents published by the Centre were disseminated among universities and Sovietologists in the U.S., Canada, Latin America, and Europe, thus increasing the authority of the material published by Nativ’s information centers. The articles of Emmanuel Litvinov, Bar’s representative in London, Moshe Decter, its representative in New York, and the publications of the Contemporary Library (sovremennaia biblioteka) in Paris gained recognition for their solidity and veracity. The founding of the Centre turned Nativ into the sole address for obtaining reliable information on all issues connected to Soviet Jewry.[29]

The difficult years of searching paid off. In the future Nativ was to play a central role in the struggle to save Soviet Jewry. The infrastructure that it created and the connections it established were important tools in implementing major international undertakings and in continually building up pressure on the Soviet regime. There would be plenty of hitches in the forty year-long unremitting struggle against the “evil empire.” There would still be outmoded clichés and a misunderstanding of the nature of the Soviet regime and its vulnerabilities; a lack of understanding of Soviet Jewry and their motivation; arguments with activists; and not always successful attempts to direct everyone and manage everything. But in the final account, the structure created by Nativ proved most effective and responsible.

As the historian Nora Levin notes, with Stalin’s death:

Mass arrests, bloody purges, and the atmosphere of deadly terror disappeared. The paranoiac excesses of Stalinism had ended. For Jews, the inflamed anti-Semitism of the “doctor’s plot” had eased, and persecution of individuals had stopped. The exiled and imprisoned were returning home. For the world there was détente with the West and China, reconciliation with Tito, cultural exchanges, a more human face to Soviet communism…. [30]

Stalin’s deified image and numerous depictions disappeared from public life. The annual awarding of the Stalin prize was discontinued; the history of the party and the Soviet state was rewritten. The country breathed more freely. Diplomatic relations with Israel, which had been severed on February 9, 1953, were restored in June. From April 1953 the anti-Israel rhetoric began to subside.

In his first years in power, Nikita Khrushchev appeared to be an effective and powerful leader who cultivated a collective Soviet leadership style. Based on the title of a novel by Ilya Ehrenburg, this period acquired the apt name “The Thaw.” Khrushchev initiated a gradual, carefully controlled and monitored process of “destalinization” of Soviet society. A young generation that was not burdened with the suffocating fear of the regime that was so characteristic of the Stalinist period began to mature. Some people even dared to renew correspondence with their relatives in Israel and other countries and began to receive parcels from them.

The Jews reacted in various ways to the changed conditions. The majority still hoped that with the end of the antisemitic campaign they could integrate into the surrounding society. Others no longer saw their future in the Soviet Union. Having learned the lessons of the war and Stalinist repressions, they thought of repatriation.

In this period small informal groups in Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Odessa, Riga, Vilnius, Lvov and other cities throughout the USSR continued to meet to discuss topics of Jewish interest. Some groups had formed in the early euphoria of the post-Stalinist era; others were comprised of men and women whose commitment dated to an earlier time: older people who had been Zionists in pre-revolutionary Russia or younger Jews who had grown up in the Western regions, where they had been educated in Jewish schools…. Baltic Jews in particular have pointed out that they needed no outside influences or confrontation with antisemitism to be reminded of their Jewishness; …they had never been cut off from their roots.[31]

Israel and everything related to it was the main topic in the nationally-minded groups. Those with knowledge of Yiddish, Hebrew, or English would listen to the Voice of Israel broadcasts and provide information to others. Although the regime began to jam broadcasts in Yiddish in 1954, those in Hebrew and English were completely accessible on short wave practically throughout the Soviet Union and on a medium wavelength in the Caucasus and Black Sea coastal area. The station Kol Tsion lagola (the voice of Israel for the diaspora) informed Soviet Jews of the various sports competitions in the USSR in which Israeli sportsmen took part. The extent of a Jewish presence at these competitions and the crowds waiting for the Israeli sportsmen at intermediary stops on the way to Moscow testify to the fact that a considerable segment of the Jewish population was listening to the Israeli broadcasts.[32]

Some people contacted representatives of the Israeli embassy despite the risk it entailed: the Israeli delegation was under constant surveillance. At the meetings embassy workers would hand out printed material on cultural and historical topics and Hebrew textbooks that Soviet Jews had been lacking for many years. The local population submitted requests, for example, “to simplify the Hebrew in the Israeli radio broadcasts so that more people could understand them”[33] Hundreds of Soviet Jews from various cities took part in meetings of reviving Zionist groups and circles. The first wave of arrests in 1955-56 affected about one hundred people, the majority of whom were freed later.[34]

Khrushchev’s secret speech to the Twentieth Party Congress on the night of February 24, 1956 represented the peak of the destalinization process and the restoration of “Leninist norms.” This congress, the first after the death of the “leader of nations,” achieved fame because of the speech “On Stalin’s Personality Cult.” Khrushchev spoke about dictatorial rule, bloody repressions, the physical annihilation of seventy percent of the party membership from 1934-38, the use of torture in order to obtain confessions of guilt from arrestees, and the use of massive terror. He referred to Stalin’s promotion of the cult of self-aggrandizement, about mistakes that were committed during World War II, and the deportation of national minorities. Although Khrushchev did not mention collectivization, the Show Trials, or the death of millions of ordinary, anonymous citizens, the terrible charges of the communist regime’s crimes against its own people produced an overwhelming impression on the delegates.

The report was read at closed party meetings in enterprises, institutes, and kolkhozes. Universities were given a brief summary. Copies were sent to communist parties in Eastern Europe, where a leak occurred. According to one account, the Americans obtained a copy from the Polish Communist Party (with the help of Israeli’s intelligence service, the Mossad) and it was published in the West in June 1956.

Despite the fact that only part of the misdeeds of Stalin’s thirty-year rule were exposed and condemned, Khrushchev gave the country and the world a document of colossal denunciatory force that shook the ideological and moral principles of the communist movement to its very foundation.

A few months after Khrushchev’s speech, fermentation began inside the worldwide communist movement. These stirrings were suppressed in accordance with local conditions by understandings and administrative pressure (Poland) or by tanks (Hungary).

In the Soviet Union the speech was not published openly until1989, inthe fourth year of Gorbachev’s perestroika, but the terrible truth seeped through the party barriers by the end of the 1950s and shocked millions of Soviet citizens.

The Jews had no special reason to be grateful to Khrushchev, who did not single out the Jewish issue in the secret speech or later. He did not acknowledge Stalin’s annihilation of Jewish intellectuals, writers and poets, the destruction of Jewish culture, or the purposeful expulsion of Jews from leadership positions and certain spheres of activity (politics, the military industry, and party nomenclature). Even the Doctors’ Plot was regarded as an ordinary abuse without an antisemitic subtext. This was all done consciously ─ if there had been no special abuse of the Jews, then there was no need for special corrective measures, no need to restore the destroyed culture, closed theaters, institutes, societies, and organizations. Reflecting the leadership’s common viewpoint on this matter, Mikhail Suslov stated in 1956, “We have no intention of reviving a dead culture.”[35] If discrimination in job applications or acceptance to institutes of higher education was not acknowledged, there was no need for change. The leadership’s policy toward the Jews remained the same: they were doomed to total, forced assimilation in conditions of discrimination, persecution, and antisemitism.

Nevertheless, conditions changed significantly under Khrushchev: mass repressions ceased and people felt a little more secure; once again the punitive organs underwent a shake-up and for the first time they were publicly condemned. Now they had to operate more cautiously; serious gaps appeared in the party’s “sole true” line and people showed greater skepticism. “Freer” literature appeared in bookstores and in “thick” journals; new theater arose; and freedom-loving poetry burst out onto the square. Soon, however, Khrushchev began to create his own personality cult and to “tighten the screws,” but never again would there be the animal fear of the regime and blind obedience to it as under Stalin. The Thaw and the secret speech drew a line between the past and future.

Khrushchev himself was not particularly broadminded or farsighted. He possessed unrestrained self-confidence and an impulsive approach to problem solving that generally led to failure (the Virgin Soil program, corn planting, agricultural cities, Sovnarhozi, a new economic-administrative division of the country). He will always be remembered solely for his secret speech at the Twentieth Congress condemning Stalinist repressions and for the Thaw ─ by some with gratitude and by others with curses for ruining the country and the socialist camp and for delivering a crushing blow to faith in socialist ideals.

Israel’s victory in the Sinai campaign in 1956 provided Soviet Jews with an additional stimulus to the awakening of national consciousness and solidarity with Israel. The Soviet Union sided completely with the Arab side; its propaganda was active, poisonous, and insulting but not convincing. After many years of harassment, antisemitic campaigns, and purges, the majority of the Jews no longer believed the official line. The Voice of Israel and other foreign “voices” enjoyed much greater trust.

At the time a growing number of people no longer envisioned a future for their national group in the Soviet Union. Many decided to repatriate at the first opportunity. Some were able to utilize a new agreement on repatriation signed with Poland. In 1957 Jews constituted fifteen percent of all people who repatriated to Poland. The Poles knew that the majority of those Jews would continue on their way to Israel. The Soviets knew this too.

The Revival and the Regime’s Reaction to It

The Sixth International Youth and Student Festival took place in Moscow in July-August 1957 under the aegis of the World Federation of Democratic Youth. An Israeli delegation participated in the festival.

At the festival it was possible to listen to western music, speak about the marvels of western technology, watch performances of dance and musical troupes, and exchange souvenirs and lapel pins. “In the unusually exuberant mood of the Festival, tens of thousands of Jews, including many from outside Moscow, came to see the Israeli delegation. …the Soviets sought to demonstrate their new liberalism by removing many of the constraints to which Soviet citizens were normally subjected for the course of the Festival.”[36]

“Each of the Israeli performances turned into a demonstration, with emotions running high on both sides. Greeted with stormy ovations and knowing what their performances meant for their largely Jewish audiences, the Israelis gave of their best.”[37]The Jewish youth experienced the same emotional charge, the same electrified feeling as at the meeting with Golda Meir ten years earlier.

The demonstration of solidarity with Israel was not lost on Western observers, who regarded the Jews’ attitude as understandable: they were not given the opportunity to lead a normal national life; they had been forcibly assimilated while simultaneously discriminated against and humiliated as Jews.

In the period between the Youth Festival and the Six-Day War, Zionist activity in the USSR gradually broadened in scale. Ties with the Israeli embassy grew closer and there were more frequent meetings with Jewish tourists from abroad and with Israeli delegations who came for scientific conferences, symposia, sports competitions, or exhibitions. More books began to arrive in various ways. Western radio broadcasts also played an important role. In sum, the Iron Curtain lifted a bit and information about the life of Soviet Jews reached the West while information about Israel and the Jewish diaspora penetrated into the USSR.[38]

The few remaining synagogues regained an important place in Jewish life, becoming a natural and legal meeting place for Jewish youth. There they were able to meet foreign tourists or members of foreign delegations, who didn’t miss the opportunity to attend services on the Sabbath.

In this context older groups of nationally-oriented Jews continued to operate in Moscow, Leningrad, Gorkii, Kiev, Kharkov, Rostov-on-Don, Baku, Riga, Vilnius, and other cities, and new groups arose. The members would meet to discuss events in Israel, to study the Hebrew language and Jewish history, and to disseminate knowledge that would facilitate the awakening of Jewish national consciousness.

The Leningrad group of Gedalia Pecherskii and Evsei Dynkin studied Hebrew and prepared to teach it. In 1957 the members of the group applied for permission from the Minister of Education of the RSFSR and the Leningrad municipal executive committee to organize the study of Hebrew, Yiddish, ancient and modern Jewish history, and literature. In response the authorities closed the Jewish section of the Leningrad Saltykov-Shchedrin library.[39]

Another Leningrad group translated the book The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising from Yiddish to Russian, printed excerpts from Maxim Gorkii’s works about the Jews, and received material from the Israeli embassy and distributed it.[40]

Former prisoners of Zion played an important role in the revival of Zionist activity in the Soviet Union. In this connection Meir Gelfond noted: “A national Zionist ideology predominated among the Jewish prisoners in Soviet camps” and in the second half of the fifties “groups of such people who shared a common past, a common ideology, and common hopes for the future, were formed in various Soviet cities.” According to Gelfond, such groups also arose in places where former prisoners had settled in exile such as Karaganda, Norilsk, Omsk, and Vorkuta.[41]

The expanded Zionist activity created a greater demand for Hebrew-language instructional material. Wherever Israelis showed up, they received requests for dictionaries, grammar books, and other educational textbooks.

Jewish samizdat (material that was produced in circumvention of the censorship) gained in significance. The Moscow group of Shlomo Dolnik and Ezra Margulis engaged in the production and dissemination of samizdat; they maintained ties with similar groups in Riga, Kiev, and other cities. David Khavkin’s group was also active in Moscow. The Podolskii-Brodetskaia group maintained contacts for a long time with the Israeli embassy, receiving material from them and disseminating it. Izrail Mints, a former Israeli and Prisoner of Zion with an excellent knowledge of Hebrew, played an active role in Jewish samizdat and Hebrew teaching in Moscow. He succeeded in transmitting his knowledge of the language and love for Israel to his students.

The regime was dissatisfied with the growth of the Zionist movement but it had to take into consideration the pressure from leading Western leftists, including members of the communist parties of Italy, France, and Canada.

The measures to suppress the Zionist movement were harsh but limited. At the beginning of 1957 the activists Baruch Waisman, Meir Draznin, Hirsh Remennik, and Yakov Fridman were arrested and charged with Zionist activity and with keeping and disseminating anti-Soviet material. Draznin received a ten year sentence, Remennik eight, and Waisman and Fridman received five years each. In Riga the activists Yosef Shnaider and Yurii Kogan were arrested on charges of listening to Israeli radio broadcasts, slandering the Soviet Union in letters to relatives in Israel, and so forth. In Odessa Zolia Katz was arrested and after a year-long investigation she was sentenced to eight years of imprisonment for hostile nationalist propaganda.[42]

In Moscow in April 1958 Dora, Shimon, and Baruch Podolskii and Tina Brodetskaia and her stepfather Evsei Drobovskii were arrested; in December of that year David Khavkin was arrested. Zionist activists in Minsk, Dushanbe, and other cities were also arrested. All received various prison terms.

How many years did you get? I asked David Khavkin.

Five years of general regime.

Was it hard?

No. On the contrary, it was the most interesting time in my life. I met very interesting people there and remain friendly with them to this day.

Were there Zionists there?

Yes, there were Zionists and ordinary Jews who under our joint influence also became Zionists.

Did you stay in the “family,” David?

Yes, this was natural in political camps. When a group would arrive from transit, the Lithuanians would meet the Lithuanians, the Ukrainians the Ukrainians, and the Jews would meet the Jews.

Was there enmity among the “families”?

On the contrary. We maintained rather good relations with the Ukrainian nationalists and the Lithuanians. They attended our holiday celebrations and we theirs.

Did Boria Podolskii serve time with you?

Yes, and also his father; his mother was in the women’s camp. He was totally skinny in camp, like an Auschwitz prisoner. And other prisoners would keep watch to see just when he was alone and defenseless so they could beat him up. I was beside myself with anger.

Were there any other Zionists there?

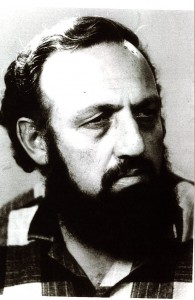

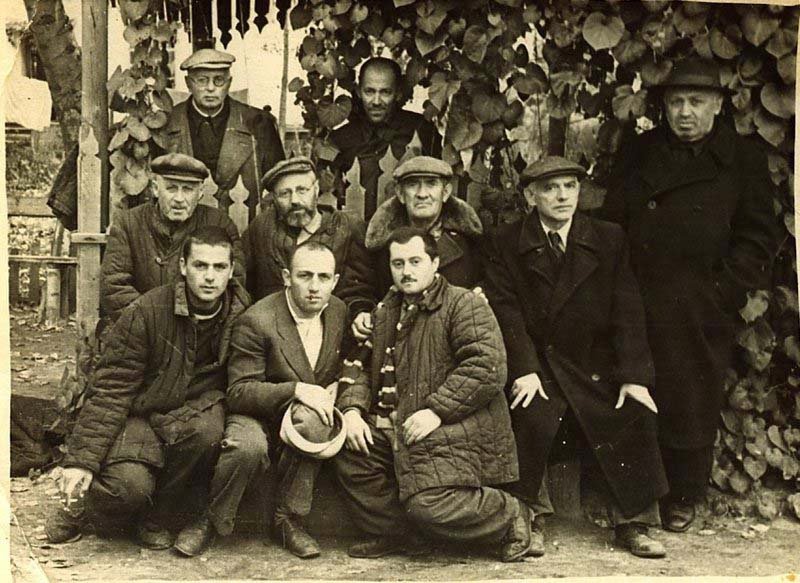

Prison camp, 1960. First row l-r: Dov Sperling, David Khavkin co, Yosef Shnider; second row:? Krasnov, Tsvi Remennik, ?, Asher Yudelevich (Bund); standing: ? Draznin, ?, Shimon Podolsky.

David Mazur, Tina Brodetskaia, and Anatolii Rubin.Tina was arrested in the same case with the Podolskiis. Boria was seventeen years old at the time and she was a little over twenty.

Did you serve the full term?

No, my case was reviewed at the request of my mother, who was very ill. In the course of the review the article under which I was charged was changed. The new article carried a term of up to three years but I had already been imprisoned longer than that so I was released after the review.

Did you go to live at the101 kilometer marker? [The distance outside of Moscow where former prisoners were allowed to reside.]

No, at first I went to Odessa because it was, after all, a Jewish city where the first Zionists lived. But I didn’t remain there long. I traveled often to Moscow and stayed with friends or my sister. After a year I spent almost all my time in Moscow. My father put in a request, explaining that they were elderly people and it was hard for them to manage alone; finally I obtained a residence permit.

Did you return to the synagogue and sing there again?

And how; after my release, everything began for real. Until my arrest I was much more cautious.

In that period Riga Zionists played a central role in the expansion of the Jewish national movement: they included Iosif Shnaider, who returned to Riga after his imprisonment in 1958, and I. Egelberg, arrested in 1959 and continuing his activity after his release, David Zilberman, and David Yafit. Later they were joined by Gesia Kamaiskaia, Boris and Leah Slovin, and Mark Blum. D. Zand dealt with the organizing of clandestine ulpans in Riga. Herman (Yirmiyahu) Branover began his Zionist activity in Riga.[43] In the middle of the 1960s a new youth group was formed that included Boris Druk, his wife Rivka and her brother Iosif Mendelevich. They rented a dacha in a Riga suburb and began to study Judaism and other Jewish topics as preparation for future emigration. Using a second-hand typewriter that they had purchased, they also disseminated typed excerpts from books they had obtained.[44]

Shnaider maintained contacts with groups in Vilnius, Leningrad, Kiev, and Moscow. The durable links forged while serving terms together in camps or prisons played an important role in these contacts.

Prisoners of Zion Yosef Khorol and Meir Gelfond created a similar network. Khorol returned to Riga in 1958; Gelfond obtained a permit to reside in Moscow after he married a Muscovite in 1959. Like Shnaider, Khorol and his friends translated, adapted, and copied material that was then given to Gelfond for distribution in Minsk, Kiev, Moscow, and in the Urals.

Among the active Zionists in Kiev were Anatolii Feldman, Nelli Gutina, Evgeniya Bukhina, Emanuel (Amik) Diamant, and Anatolii Gerenrot. They translated articles about Israel, Judaism, and antisemitism into Russian and disseminated them. The Kiev group was in contact with activists in Riga.

In Leningrad in the fall of 1966 agroup was formed with the goal of fighting assimilation and studying Hebrew. The group included Grigorii Vertlib, Ben-Tsion Tuvin, Hillel Butman, Solomon Drezner, and Aron Shpilberg. They opened their first ulpan at the beginning of 1967 ina skiing area near Leningrad. By the spring of 1967 the group had grown to fifteen people.[45]

Anatolii Rubin played an important role in the revival of Zionist activity in Minsk. Arrested in 1958 and sentenced to six years of imprisonment, he continued his Zionist activity after his release. In Georgia the orientalist Shalva Tsitsuashvili played an active role in the Zionist revival.[46]

Eitan Finkelshtein initiated the Zionist movement in Sverdlovsk. At the end of the 1960s he moved to Vilnius, hoping that it would be easier to emigrate from there. He had contacts in Moscow and other cities. He sent a large quantity of samizdat material to Sverdlovsk and did it so ably that the local KGB did not know about our existence (my Zionism also began in Sverdlovsk ─ Yu. K.) until the sentencing in the Leningrad hijacking trial when we organized an open protest.

The Jewish samizdat at first developed under the influence of the general democratic samizdat, which was already in full swing in the 1960s. Among the intelligentsia it was almost considered good taste to obtain, read, and transmit to others literary works and other samizdat material that had circumvented the censorship. It was the period of the impetuous flourishing of the bards such as Okudzhava, Kim, Vizbor, Gorodnitskii, Vysotskii, and Galich with their rebellious spirit that did not recognize any official canon. Taped recordings of these singers were disseminated throughout the country and could be heard at tourist gatherings and from the windows of student dormitories. In this atmosphere Jewish youth also felt unfettered and participated in the general samizdat.

In this context there were grounds for the Jewish activists’ assertion that the dissemination of Jewish samizdat was not directed against the state because it did not aim at reforming the Soviet order; its ultimate goal was promoting emigration from the country and repatriation to Israel.

Relations between the Jewish and general democratic movement were marked by mutual assistance and sympathy, particularly because there was a high percentage of Jews among the democrats. The joint time spent by activists of both movements in imprisonment further reinforced these relations. The goals of the movements, however, were different. Many Jewish activists (including myself ─ Yu. K.) considered it wiser and more prudent not to waste the energy of Jewish nationalists on the alien and possibly dangerous task of the general reformation of the country. We had enough problems of our own, which only we ourselves could solve. The members of the Israeli embassy also warned Jewish activists against participating in the democratic movement.

On the twentieth anniversary of the massacre at Babii Yar, in September 1961, Evgenii Yevtushenko published his famous poem “Babii Yar,” which resounded as a powerful, sincere protest; its words tore apart the dense spider web of antisemitism that enfolded Soviet public consciousness. The poem became a symbol provoking many disputes.[47] A year later Shostakovich composed his Thirteenth Symphony, basing an aria on Yevtushenko’s verse. The Jews began to fight for the erection of a monument at Babii Yar. Fifteen years later, in 1976, it would finally be set up but without any mention of the mass shooting of Jews.

The Jews of Vilnius petitioned for the building of a monument and fence around the mass grave of thousands of murdered Jews at Paneriai. A monument with an inscription in Yiddish had been set up after the war but the authorities destroyed it in 1952. Later, an official monument was placed at this site but it, too, did not mention the Jewish victims.

The mass grave of 38,000 Jews at Rumbula outside of Riga became a meeting place for Jews. In April 1963 on the eve of the twentieth anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, the Riga Jews Zalman Baron, David Garber, and Mark Blum brought an obelisk-shaped board to this site. Having received permission to clean up and maintain the site, Riga Jews began to go there in greater numbers. In the fall of 1963, about 800 people went there to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the massacre of Riga Jews at Rumbula. It gradually became a legitimate meeting spot, where thousands would gather on the two anniversaries, arriving not only from Riga, but also from Vilnius, Leningrad, Kiev, Moscow, and other cities. None of those who assembled there had any doubts ─ these meetings were dedicated to the struggle for repatriation.[48]

The tours of Israeli artists who arrived in the framework of cultural exchange programs turned into demonstrations of solidarity. They invariably performed to full houses. Israeli singer Geula Gil was the most popular, giving three concerts each in Moscow and Riga and one each in Vilnius and Leningrad in the summer of 1966. People stood on line all night for tickets.

Sports competitions in which Israelis participated were also very popular. No one questioned why the Israelis had so many fans.

Film festivals in Moscow in 1963 and 1965 acquainted viewers with Israeli films. Thousands saw the films Kibbutz and The Glass Cageabout the Eichmann trial and the Holocaust.

L-r:David Khavkin, Yigal Alon, Grigorii Feigin and wife of Yigal Alon, Moscow Agro-industrial exhibition, Israeli day, 1966

Two Israeli exhibitions in 1966 on the agricultural and poultry industries provided occasions to meet with Israeli representatives. The Israeli pavilion at the agricultural fair in Moscow in the spring became a meeting place for Jews from all over the Soviet Union.

The regime could not prevent Israel from participating in the events but it was extremely disturbed by Soviet Jew’s massive solidarity with the State. Anti-Israeli propaganda was intensified and several people were arrested.

At the start of the 1960s the Jewish national movement did not yet have generally acknowledged leaders, organizational structures, or forums for discussing basic issues. It was a movement born of circumstances and necessity that developed without discipline or coercion; evolving from isolated cells. Those who had the courage and ability to express their views and establish links with other cells, with foreign tourists, and the Israeli embassy became members of the cells.[49] The links between the various groups inside the USSR, the preparation and dissemination of samizdat, and the establishment of links abroad led to the gradual consolidation of the Jewish movement.

The Soviet authorities’ attempts to crush these national strivings were unsuccessful. Information about the difficult situation and the Jews’ aspirations leaked out to the West, stimulating world Jewry to take up the struggle for the freedom of their brethren who were languishing behind the Iron Curtain.

American Jews Join the Struggle

About two million Jews from the Pale of Settlement immigrated to the U.S. from 1880 through 1914. The Jews prospered in America, preserving their Jewishness and attaining impressive achievements. In two or three generations the American and Soviet branches of Russian Jewry diverged considerably but the American Jewish emigrants and their descendants did not forget their origins.

The Jews found America to be a country in which the authorities did not meddle in a person’s private life as long as he swore allegiance to the American constitution and obeyed the country’s laws. Religion was separate from the state. The American melting pot took in Englishmen, Frenchmen, Germans, Jews, blacks, and so forth, forming the American nation from this mixture. If you ask an American Jew his nationality, without blinking he will reply, “American.”[50] He truly feels American, ready to pass through fire and water for his country. At the same time, he regards his Jewish identity as a religious one that he is free to maintain and is no one else’s business.

As a rule, Americans retain an interest in their roots and are willing to help their countries of origin. The cultures of the new immigrants became a component of American culture insofar as they were attractive to the rest of the population. Of course everything didn’t always go smoothly but, on the whole, in one or two generations the Jews from the shtetl became Americans without losing their connection to their own religion, culture, tradition, and customs. They enthusiastically became part of the country’s life, putting down roots in its bountiful soil and succeeding along with America.[51]

Over the same period the Jews who remained in Russia suffered through a series of pogroms, persecutions by the tsarist regime, war, destruction, revolution, civil war, starvation, war communism and much else that has already been described. Along with the rest of the population they built communism, a so-called heaven on earth in one separate, destitute and backward country. “Don’t make a wish ─ it may come true,” says an old Chinese proverb. The Bolsheviks built an indigent, totalitarian police state possessing enormous military might. Soviet Jews were able to taste from the tree of knowledge but at the same time they were subjected to very harsh, enforced assimilation. They were fed poisonous lies about their own people and taught to be ashamed of their Jewish origin.

Nevertheless a Jewish spark remained ─ respect for benign national traditions, a feeling of a common historical fate, and perpetual attraction to their own. Those who were willing to meld into the population were not, however, allowed to forget their origin. On the whole, Soviet Jews remained Jews in their own eyes and in the eyes of those around them even though they were rather forcibly cut off from Jewish culture, religion, and tradition. Many in Israel and the West would call them “Jews without Jewishness.”

Of course, there was and is antisemitism in the U.S., too. The waves of ethnic immigration brought Old World attitudes with them. American Jew recognized this danger and fought its manifestations.

When the scale of the catastrophe became clearer after World War II, it led to a feeling of trauma in the Jewish community.

Why, I asked Jerry Goodm, did American Jews support OUR struggle for repatriation so powerfully and effectively but did not apply the same pressure to save their European brethren? Why were they so impotent?

It was a different world, answered Jerry, and therefore a different Jewish community. At the end of the 1930s and during the war, it was not yet so organized. It consisted to a considerable degree of immigrants born in Europe, like my parents, who would not think of opposing the authorities. Although some people think that nothing was done, that’s not true. There were demonstrations and protests but not the massive ones or the kind of organization that appeared after World War II.

After the war certain changes took place in the community. First, a generation born in America grew up that spoke English, was capable of working with the media, and knew how to approach people in Washington. Second, the preceding generation was poor, mainly representing the working class. My parents, for example, worked in a factory. After World War II the community included various types of professionals, businessmen, and people who not only had access to power and the media but also, unlike the parents’ generation, had the financial resources that could be utilized to fund certain activities. Third, in organizational terms, in the 1960s you had a grassroots network already in place which did not exist previously, like the Jewish Community Relations Council.

Did the Holocaust play some role in this?

Undoubtedly. We had young people whose parents managed to survive during the Holocaust, and there were people who had gone through all this themselves. The slogan “Never again” meant that never again would we let the Jews go like lambs to the slaughter. I don’t think that this correctly describes what happened. You and I know that far from all European Jews went obediently to the slaughter. In fact, many died as heroes. Jews participated in the partisan movement; five hundred thousand fought in the Red Army; and many fought in the French army. We know of Jews who attempted to struggle in the death camps. Nevertheless the myth persists, like many such myths, having some truth to it.

When I was director of the National Conference, the parents of a staff member in our New York division, Zissy Shnur, were Holocaust survivors. Incidentally, her parents didn’t tell her about this when she was a child and she discovered it much later. But she grew up surrounded by people like her parents, which reinforced her motivation to work in our organization. Take my own case: my grandfather was murdered in the Riga ghetto. When I was still a student, I traveled to Russia and met my sole remaining uncle, who told me his personal story. Several years later, when I was already a young Jewish community worker, I heard about the Jewish activists in Riga who had fought and were persecuted. My family story and these new persecutions combined into one picture. A new Jewish American profile thus appeared after the war. You Soviet Jewish activists were dealing with an America that had begun to feel its guilt for its failure to save Jews during the war.

A feeling of guilt?

Why, for example, did Senator Jackson join our struggle? When he first approached the leadership of the National Conference with the idea for his amendment, he told us, “I myself am the son of immigrants. I know what it means to acquire a homeland.” Influenced by the history of the Holocaust that came out in the 1950s, people began to say that Americans could and ought to do more and this affected many members of the Congress. Jews who did not yet have voting rights during the Holocaust but now wielded some influence said, “If someone forgot about this tragedy, we shall remind him.”

At the beginning of the 1960s the Soviet regime initiated a campaign of arrests for economic crimes. Almost all the people convicted in these trials had Jewish names. Western public opinion was aroused when “the West heard that the death penalty was being invoked for these offenses. And this even though one of the cornerstones of the USSR’s new criminal code was that the death penalty was limited to those found guilty of ‘high treason, espionage, sabotage, terrorist acts, banditry and premeditated murder…. under aggravated circumstances.’”[52]

In the same period in the U.S. the struggle for the rights of Blacks got underway and somewhat later the campaign against the Vietnam war started. Many young Jews participated in both efforts, gaining experience and honing their skills in the techniques of conducting such campaigns.

When we held our first conference on Soviet Jewry, Jerry Goodman told me,[53] we didn’t know anything about you. There were no refuseniks; we hadn’t heard of Kosharovsky and Natan Sharansky had just been born. We organized the conference because Jews had been arrested for economic crimes. I’ll never forget it! We were so ignorant and so emotional. At our meeting in Philadelphia we drew up an eighteen-point declaration on the rights of Soviet Jews. Seventeen of them dealt with culture, religion, and Hebrew. The last one was about family reunification. You were still the “Jews of silence.” Many of us thought that Elie Wiesel had American Jews in mind when he coined that phrase, but he had all of you in mind. When Afro-Americans began to found their civil rights movement, many young Jews joined this movement. Later they refocused their feelings and their practical experience in the movement to work in support of Soviet Jewry. Some of the first members of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry organization, including myself, had been members of the civil rights movement. At the time we rather simplistically perceived the liberation of Soviet Jews as a civil rights movement and without thinking we jumped into those waters.

Soviet Jewry became a hotter topic as people became more aware of the horrors of the Holocaust and also learned about the harassment of Soviet Jews by means of arrests and trials for economic crimes. American Jews reacted in a traditional manner by establishing an organization to deal with the matter ─ in this case, four organizations! The most prestigious and powerful of them, founded by the establishment at the initiative of and in cooperation with Nativ, was later called The National Conference for Soviet Jewry. Similar organizations were established in France, England, Canada and other countries. The “Conference” enabled Israel in some measure to coordinate the complicated mechanism of interaction between the various organizations in the U.S. and to eliminate their independent and muddled scurrying “above” to higher authorities.

The remaining organizations arose at the initiative of private citizens. These included the Union of Councils for Soviet Jews, whose founder and first president was the NASA scientist and Jewish activist Louis Rosenblum; The Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, whose founder and first national director was Jacob Birnbaum; and Rabbi Meir Kahane’s Jewish Defense League, which appeared in 1968 and became involved in Soviet Jewry advocacy a year later. “Private” organizations were often in competition with each other and the establishment. Frequently opposed to the establishment and its policy to some degree, they often forced it to change strategy and tactics.

Such opposition corresponded to the spirit of the times, which was characterized by a rejection of accepted values, the overthrowing of idols, civil disobedience, and a struggle against everything that was establishment or resembled it. Youth rebelled against parents and “flower children” refused to wear normal clothing or live in polluted cities. With regard to the Soviet Jewry movement, the term “opposition” had a somewhat different meaning. It was not so much a revolt against the establishment as an attempt to push it toward greater activity. Unwilling again to commit the sin of inactivity of the older generation during the Holocaust, Jewish youth repeatedly put the establishment in an awkward and even foolish position by their criticism and desperate acts.

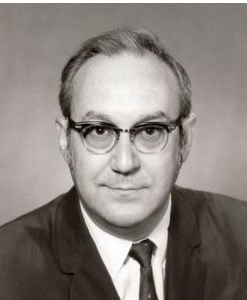

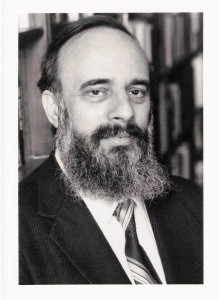

Jacob Birnbaum, the founder of the organization “Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry”, photo 1986, co Remember and Save

“We don’t need a Conference, we need a struggle,” said Rabbi Jacob Birnbaum in this context, and three weeks after the formation of the American Conference, he convened a founding meeting of the independent organization “Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry.” At the same time, Birnbaum understood that without the establishment with its resources, organizational possibilities, and socio-political ties, it would be extremely difficult if not impossible to influence an enormous power like the Soviet Union. He therefore always sought to cooperate with the establishment and saw his organization’s role as a testing ground for checking various forms of struggle and for elaborating the correct strategy to use against the USSR.