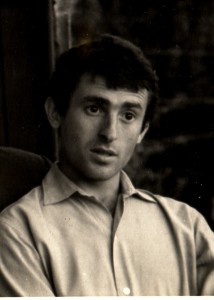

Boris Kochubievsky was born into an assimilated Jewish family that experienced all the vicissitudes of a difficult and troubled period. According to family lore, one of his maternal great-uncles named Kaiserman served as one of two Jewish ministers in the government of Simon Petliura’s[1] independent Ukraine and was shot by the Reds as a Petliura man around 1920. Another relative was a commissar and was executed as a Trotskyite at the beginning of the 1930s. A third with the rank of admiral was shot in one of the Stalinist trials against the military in 1937-38. His grandmother and grandfather were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists at the beginning of World War II. His father, an officer in the Red Army, perished at the very start of the war. “I have had a very difficult fate,” recalls Kochubievsky,[2] “I try to escape my past because there was too much of it. My parents divorced; my father went to the front, I wound up in a family of strangers…an orphanage, vagrancy… My mother found me after the war but I ran away from home and again led a vagrant’s life…. I was kicked out of school and expelled from the Pioneers, from the Komsomol….”

The Bolsheviks, Ukrainian nationalists, Germans, and Russian were all murdering the Jews. Boris didn’t understand why this was happening and no one could explain it to him. He did not receive any Jewish education but the tough school of life taught him how to find a way out of difficult situations. With a childhood like that he managed to finish night school with a medal, register as a Russian in his passport (it was 1952, one of the darkest periods in the history of Soviet Jewry), begin studies at the night school of the Kiev Polytechnic Institute (he had to work in the day) and to complete his degree in the field of radio engineering. Later on, he again changed his nationality and registered as a Jew. He was twenty-five years old when the poet Evgeny Yevtushenko published his famous poem “Babii Yar”—about the spot where Boris assumes that his father was shot. In those days Kievan Jews’ attempts to establish a memorial there were unsuccessful.

He was already thirty years old when the Six-Day War broke out. Many were offended by the flip-flops of Soviet propaganda on the eve of and after this war but very few had the courage to get up during a meeting when “Israeli aggression” was being condemned and declare loudly, “I disagree.”

At that time almost all large enterprises held mass meetings. The party speaker would present the official viewpoint, a prepared resolution would be put to the vote, and its unanimous acceptance would be reported to the higher-ups as evidence of universal popular approval of the party and government’s policy. That was the ritual. “I disagree,” declared Boris, “and I want it to be written in the protocol. Israel was not an aggressor. This war was its defense against complete physical destruction.” The secretary of the party organization demanded an immediate halt to this “anti-Soviet speech” but Kochubievsky could no longer stop…. He was subsequently condemned at a trade union committee meeting and asked to leave the factory—“preferably voluntarily.”

Later, in May 1968 he wrote an appeal, “Why I am a Zionist” that was widely disseminated in samizdat. “I’m probably not saying anything new,” he wrote.[3] “It was always that way and it remains so now. But it shouldn’t be that way! Our generation is distinguished by resoluteness and belief in this. We are convinced that there should no longer be any place for Jewish submissiveness. Silence is equivalent to death. Indeed it was such tolerance that created Hitler and the like… More and more Jews are beginning to understand that the road to Auschwitz is built on endless silence and submission. Today the leaders of the Soviet Union consign Zionism to anathema. Therefore I am a Zionist.”

In June 1968 Boris married a student in the fourth year of a pedagogical institute, and in August he applied for an exit visa to Israel. In September his wife, an ethnic Russian, made a similar application. He received a refusal “because of the lack of diplomatic relations” and she because she had “aged parents” in Kiev. Larisa Kochubievsky was subsequently expelled from the institute and from the Komsomol for her “Zionism.” Her parents—her father worked for the KGB and her mother was an award-winning teacher—renounced her.[4]

On the anniversary of the Nazi massacre, Kievan Jews gathered in small groups at Babii Yar. In 1968 the authorities decided to seize the initiative and organize an official memorial meeting. The speakers condemned “Israeli aggression” and spoke in the most general terms about the fascists who had murdered Soviet people at Babii Yar. They did not mention the Jews there….

A friend told Boris about a conversation that he overheard between two participants at the meeting. “What is happening here?” asked one. “Here the Germans murdered a hundred thousand Jews,” replied the other.” “Too few,” reacted the first one. Boris seized on this: “They talk that way because on this day and in this place they condemn ‘Israeli aggression’ and don’t say a word about the fact that they murdered Jews here.” A man who it turned out later was a provocateur immediately approached him. “Not only Jews were killed here,” declared the provocateur. “But only Jews were killed because they were Jews,” retorted Boris. A conversation started that later was reproduced in detail in a charge against him.[5] Tall, drawn, with burning eyes, Boris was convincing in this conversation….

In November 1968 the Kochubievskys were informed that they had been granted a visa and should appear at OVIR on November 28 to formalize the documents. But that morning the police came to his home and conducted a search. Afterwards they made him sign that he could not leave the country. On the same day Kochubievsky sent an open letter to the General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee Leonid Brezhnev and the Secretary of the Ukrainian Communist Party Petro Shelest. The letter also circulated in samizdat.

A week later, on December 5, 1968, Kochubievsky was arrested and charged on the basis of Article 187-1 of the Ukrainian Criminal Code of orally disseminating notorious fabrications defaming the Soviet state and social order.

He was incriminated for: speaking at a meeting of the radio factory and union committee; the conversation with the provocateur at Babii Yar; and conversations at OVIR. “They very much did not want to charge me on the basis of a ‘political’ article,” Boris told me.[6] “At the investigation they tried to convince me: “Look, you have a few minor criminal cases. Admit any one of them and you’ll leave the courtroom a free person… If I had agreed, probably I never would have been freed.” On January 20 the investigation was completed and the case brought to trial. The court returned the case for further investigation in view of the failure to prove an intention to disseminate.

On May 13, 1969 Kochubievsky’s trial began in the same courtroom in which over fifty years before (1913) the trial of Mendel Beilis (a notorious blood libel case) took place. Although the trial was declared open, they admitted basically so-called “representatives of the public,” who were intended to create additional psychological pressure on the defendant, and KGB personnel. Twelve of Kochubievsky’s friends and relatives complained to the prosecutor that they were not permitted into the courtroom but it didn’t help.

The court rejected the defense’s testimony on the grounds that only his friends who shared his Zionist views could defend him and they, of course, could not give reliable evidence. For three days the judge attacked the defendant in a more aggressive manner than the state prosecutor, mocked him, and permitted antisemitic outbursts by the “representatives of the public,” including against his brother, who after persevering was finally let into the courtroom. Kochubievsky’s “defense” accepted all the points of the charge, declaring in defense of the accused that his actions were not premeditated and his mistakes were sincere. “At the trial I told them,” said Kochubievsky, “that I was not anti-Soviet; there was no basis to condemn me for that; and that with all my heart I wished the Ukrainian people another 500 years of Soviet rule.”[7]

Kochubievsky was convicted and sentenced to three years of corrective labor. His friends carefully recorded all the proceedings and this material circulated in samizdat. Subsequently, together with the appeal “Why I am a Zionist” and his letter to Brezhnev, the assembled material was transmitted to the West and played a significant role in mobilizing Jewish communities. Yakov Birnbaum, a leader of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry recalled, “With Kochubievsky’s arrest we had our own political ‘Prisoner of Zion.’[8] Instead of protests against abstract violations of human rights or bans on baking matzoh or the closing of synagogues, we had a live symbol of the Soviets’ persecution. In 1970 a brochure entitled A Hero of Our Time was published about Kochubievsky in the U.S.

Was it difficult serving time? I asked Boris in the same interview.

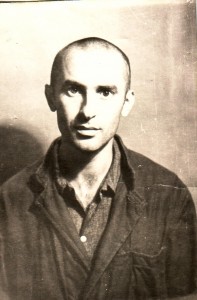

Well, they didn’t beat me, he answered. The criminals were even a little afraid of me, but of course I didn’t escape taunts. While imprisoned, I managed to send out an article that was published in The New York Times. After that they transferred me to a “crazy house” and kept me there while awaiting orders from the higher-ups. When they brought me back from there—it was the beginning of February—the temperature in the cell was minus twenty degrees centigrade. The window was broken and the water pipe inside the wall, apparently, had broken. The water seeped out of the wall and immediately froze. Picture it: winter, in the cell it was just like in the street, minus twenty degrees and the wall was all ice… But I made it through and even didn’t catch cold…just my stomach….

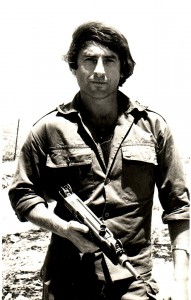

Kochubievsky served his term, was released on December 5, 1971, and received an exit visa to Israel. He lives on pension now in the center of Jerusalem.

What do you do as a pensioner?

I read.

He led me into an adjacent room full of shelves with books. “You see what a library I have!”

Do you have children?

My Russian wife remained in Ukraine; with my second wife, whom I met in Israel, I have three children. The oldest just got married; he is 31. The middle one is already married and my daughter is just getting ready. They don’t speak Russian to me at all.

Did you become religious?

It’s more like I adhere to tradition….

The difference in the fate of two Zionist activists confirmed western opposition Jewish organizations’ faith in the power of public opinion. The leaders of Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry thought that if Kochubievsky’s case had caught the West’s attention before his arrest, then instead of landing in prison he could have gone directly to Israel as Kazakov did.

[1] Symon Petliura (May 10, 1879 – May 25, 1926) was a publicist, writer, journalist, politician and statesman, a leader of Ukraine’s fight for independence following the Russian Revolution of 1917. During Petlura’s term as Head of State (1919-20), pogroms continued to be perpetrated on Ukrainian ethnic territory, and the number of Jews killed during the period is estimated to be between 35 and 50 thousand.

[2] Boris Kochubievsky, interview to author in June 2005.

[3] The appeal was cited by Leonard Schroeter in The Last Exodus (Jerusalem: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1974), p. 45.

[4] From the Chronicle of Current Events (Russ.), No. 6, February 28, 1969.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Boris Kochubievsky, interview to the author, June 2005.

[7] Kochubievsky, interview June 2005.

[8] Yossi Klein Halevi “Jacob Birnbaum and the Struggle for Soviet Jewry”, Azure, Winter 5764/2004.