Jewish and Zionist activism began long before the Six-Day War, but it became more intense after it. The war had a two-fold influence: it reinvigorated those who for many years had already been endeavoring to bring about a Zionist revival; for others it marked a watershed from which they began a return to their people.

The Six-Day War’s effect might not have been so strong if it had not exposed the Soviet regime’s true attitude toward Israel and the Jews that was manifested most blatantly in the clamorous, poisonous anti-Israel propaganda. Many found it morally unbearable to listen to this daily manifestation of the regime’s hostility while continuing to work for the Soviet state.

My experience fits in with the second group. I was totally a Soviet citizen of the 1941 model: a completely assimilated family; I joined all the youth groups—Octobrists, pioneers, Komsomol; spoke only Russian, was familiar only with Russian culture, studied well, and worked hard. I was very patriotic and took pride in the powerful country that the entire world respected and feared. The “Black Years” of Soviet Jewry (1948-1953) occurred during my youth but my family did not discuss the situation and it left no trace in my memory. Yes, there was antisemitism and discrimination but I wanted to believe that this would gradually disappear. In order to relieve the pressure of Jewish complexes I took up boxing and sport tourism. I worked at a prestigious and well-paying institute in the development of guidance systems for strategic nuclear missiles.

A month after the Six-Day War, I put in a request to quit my job at the institute. Under Soviet conditions that was not such a simple matter. Highly qualified workers were an asset to their superiors and not so easy to replace. In short, it took another six months of bureaucratic battles until they let me go.

Many future activists started this way, leaving work at closed enterprises in the hope that this move would save them from being denied an exit visa on grounds of secrecy. In fact, however, they usually remained in refusal for many years (in my case it was 18 years) and this lengthy delay spurred many to become activists in the Jewish movement.

Before the Six-Day War separate groups were already engaged in preparing and disseminating samizdat.[1] After the war the number of such groups rose sharply and they began to cooperate. The Jewish population’s distrust of the official media became more widespread. Hundreds of thousands preferred to obtain information from the foreign “voices” (overseas broadcasters such as the Voice of Israel, Voice of America, or the BBC) despite intense Soviet jamming. The movement for a Jewish national revival began to acquire a broader social base.

The processes of awakening and activation developed differently in various regions in accordance with local conditions and traditions. In some places they were limited to listening to the foreign “voices” and reading samizdat. In the Baltic republics groups actively engaged in preparing and disseminating samizdat and even in publishing their own journals and newspapers. In the Caucasus and Central Asian republics many Jews were prepared to drop everything and leave for Israel, seeing this as the fulfillment of the messianic prophecy.

Moscow was the nerve center of the national revival.

Moscow

The capital of the Russian Federation (RSFSR) and also of the entire Soviet Union was a megalopolis with a population of over ten million. It was the center of the Soviet regime’s power apparatus. It is also a center of industry, science, higher education, and culture. It houses the foreign embassies, offices of world news agencies, and the press and is the site of many of the international meetings; it is the main stop for foreign tourists. The regime solicitously watches over Moscow, which is the country’s showcase to the world. Everything that happens there falls under the scrutiny of foreign states.

Activists from all parts of the country endeavored to reach Moscow. The authorities were particularly sensitive to their activity but were limited in the range of oppressive measures that they could use.

Moscow was the focal point of highly educated people and intellectuals, particularly so in the case of the Jewish population. “It was in Moscow in February 1966 that the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel were tried.[2] It was there, in succeeding months, that the democratic movement took coherent shape…. Jews…were numbered among the victims and among the democratic activists out of all proportion to their representation in the population….”[3]

According to the 1970 census, 250,000 Jews were living in Moscow. They were dispersed throughout the city although they were concentrated more densely in certain areas. Mikhail Chlenov recalls, “My class consisted of three national-ethnic groups: one-third Russian, one-third Jews, and one-third Tatars. Previously it had been a completely Jewish residential area: Tverskoy Boulevard, the Arbat, the Ring Boulevard up until Sretenka, Kirovskaia. The lay-out was usually the following: the Tatars lived in the basements, the Jews on the first floors, and the Russians higher up.”[4]

There were two operating synagogues for the entire city: the Choral Synagogue in the center of town on Arkhipov St. and a small Habad one in the area of Marina Roshcha.

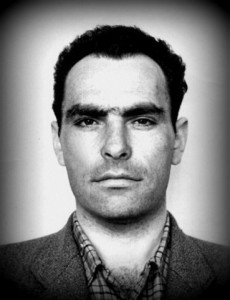

“In Moscow,” writes the historian Benjamin Pincus, “there was a strong group of activists with rich experience in the struggle to reach their goals and with a heroic past…. Two who stood out in this group were Vitalii Svechinskii and Meir Gel’fond…. In addition, the core of founders of the ramified Zionist activity in the period 1967-1972 included David Khavkin, Tina Brodetskaia, and Izrail’ Mints.”[5] This nucleus had all been imprisoned in Soviet corrective labor camps.

The soul of the group was David Khavkin. “We regarded Khavkin as the Moscow Moses,” recalls Vitalii Svechinskii.[6] “He liberated the Jews from fear and did it well. Although a solid, tough fellow, he was amazingly tender to his own.” “We would gather at David Khavkin’s,” adds Eitan Finkel’shtein, “to celebrate all the holidays. He started the tradition of gathering near the synagogue. Previously the young people who sang and danced would not go there. But he would come with a guitar, an accordion, or a tape recorder.”

In 1958 Khavkin was arrested and sentenced to five years. After his return from the Mordovian camps, he renewed his Zionist activity. He thus played a role in initiating gatherings near the synagogue, the copying and dissemination of Jewish songs, spreading information about Israel, providing instruction in Jewish dances, and the organization of Hebrew teaching. Possessing unique energy and physical strength, Khavkin succeeded in attracting people and instilling in them a feeling of pride in their nation. While imprisoned, Khavkin acquired new friends with whom he continued to maintain close contacts after his release. His fame spread far beyond the Moscow limits:

It was to Khavkin that Ruth Aleksandrovich brought the young Riga activists for advice and guidance. It was to Khavkin that Mogilever, Dreizner, and Butman would come for consultation and the sharing of ideas. Schooled with other dissidents in the labor camps, he stressed legalism and the right to emigrate under the Soviet Constitution and international law. Knowing that he was under continual surveillance by the KGB, Khavkin perfected surreptitious techniques and was always careful not to overstep the limits that would lead to his entrapment and the destruction of the movement.[7]

When Khavkin left for Israel in September 1969, over 500 people accompanied him to the airport. After his departure, the apartment of Vitalii Svechinskii became the natural meeting place and center of Jewish activity.

Svechinskii was born in 1931 in Ukraine in the city of Kamenets-Podolsk (within the limits of the Pale of Settlement). When he was two years old, his parents moved to Moscow, where he grew up.

You know, Vitalii recounted with a laugh, there is a misconception that the Jews came out of Egypt.[8] In fact, they made their exodus from the Ukraine. I came from an assimilated family; my mother was a pianist who played in the municipal orchestra. My father was a fervent Komsomol member back in the Ukraine. In Moscow he began studying at the Oriental Institute in the Chinese department. In his third year he was recruited into the GB [state security apparatus]. They told him, “Either you join or [put] your party card on the table.” At that time the Great Patriotic War [Soviet terminology for World War II] began and he went as a volunteer to the front although they didn’t take him right away; he tried for a long time. At the front he landed in the cavalry army of Dovator[9] and was an excellent cavalryman. They reached the German rear and created the appearance of a partisan movement. When the war ended, he already had the rank of a KGB major.

Was he affected by the postwar anti-Jewish campaigns of the period 1949-52?

They had already thrown him out of the security service. In a manner of speaking, in this case he was lucky because I was arrested in 1950 and he was automatically fired because of unsuitability for the job.

What did you undertake upon your return to Moscow in 1955?

First I began to look for my former acquaintances in Moscow. Thanks to my old camp ties I found many former zeks [Russian abbreviation for prisoners]—Jews and non-Jews—and noticed many very interesting processes. I was struck most of all by the amount of samizdat. Whole books were being copied at night, secretly, and handed from one to the other. A colossal amount of literature appeared that touched the heart directly. Samizdat affected people like a refreshing elixir. People woke up from a stupor, and they understood where and how they were living, who they had become and who they were.

Do you recall something from the works of that time?

I was impressed by The Sources and Meaning of Russian Communism by Nikolai Berdiaev.[10] After that I read everything by Berdiaev that I could get my hands on. Then there was Jabotinsky —his essays—Feuilletons. When I read them I was stunned; it became my primer. It contained so much truth, wisdom, strength, energy, and courage that we choked up. These were not feuilletons but powerful essays that you can read even now and they are meaningful. I typed them at night. There were excerpts from Pinsker’s Autoemancipation and some translations from Hebrew, prepared by Meir Gel’fond’s group. At first I encountered the non-Jewish movement—Crimean Tatars, Baptists, democrats. Among them were my camp friends such as Vitia [Viktor] Krasin and Petr Yakir. I knew Petr Grigorenko, Il’ia Gabai, Andrei Amalrik, Pasha [Pavel] Litvinov[11]…I used to frequent their homes.

How did you resolve the issue of your relationship with the democrats?

I debated with them. I tried to prove to Iakir that what they were doing was very good but Iakir’s place was not there. Sarra Lazarevna, Iakir’s mother, attacked me: “What are you doing! Isn’t it enough that he is tied in with the democrats, who oppose the Soviet regime; you want to foist Jewishness on him in addition so that he would go to jail for two articles at once?” You know, it’s like the joke when a Black was reading a newspaper in Yiddish on the New York subway… I was well acquainted with Tolia [Anatolii] Iakobson[12] and Nadia Emel’kina, who went out to defend Volodia [Vladimir] Bukovskii. I knew Volodia very well. I was astonished when he got out of prison and right away, without any break, became very active. It turned out that he wrote a doctorate on psychiatric prison hospitals[13] and smuggled it out to the West. This attracted considerable attention and he again landed in prison. I saw all this and understood well what was going on.

Did you see yourself more as a Jew than a dissident?

When the trials of Ginsburg, Galanskov, Dobrovol’skii, and Lazhkova[14] began in January 1968, a letter made the rounds, and, as Lenia Vasil’ev used to say, “As an honest person I signed it.”[15] This letter became know as the Letter of the 170. I calculated that about seventy percent of the signatories were Jews. I then went to Litvinov: “”Pasha,” I said, what are you doing, only Jews… is it possible that way?” Pasha smiled and replied, “In the struggle for human dignity and honor it doesn’t matter whether you are a Jew or not. Only one thing has meaning—whether or not you can pay for it (you’re willing to take the consequences).” Later I wrote an article about the Jewish participation in dissident movement.[16]

How did you get to Zionist circles?

Khavkin was the first serious person who did something in the situation of 1967-68. We developed a good relationship from my first visit to him when I told him that OVIR had begun to accept documents not only from direct relatives. That’s a whole story. In the summer of 1968 I went to Kiev to my spiritual father Natan Zabara, who had brought me gruel when I was imprisoned in camp… I loved him; he was like a father to me. Zabara said, “I want to introduce you to some young Jews here; perhaps you can be helpful to them.” “What kind of young Jews?” “They come to me and I teach them Hebrew and this and that…”

He taught Hebrew in Kiev in 1968?

Yes. He was a Yiddish writer. His Hebrew was weaker than Druker’s but still…. His book, Hagalgal hahozer (The wheel of eternity) recently came out in Russian translation.[17] Natan introduced me to Tolya Gerenrot, Zhenia Bukhin,Gena Koifman, Amik Diamant—the whole group. They invited me to the forest where they sang Israeli songs, danced, and played music. A hora! I almost went crazy. There was nothing like this in Moscow. There was one ex-zek (former prizoner) among them, Alik Feldman, with whom I found a common language. I look and I’m simply filled with envy… Kiev is something! I say to Alik, “I don’t see anything like this in Moscow.” He tells me, “I’ll give you the phone number of my friend from camp. His name is David Khavkin.”

Upon my return to Moscow, I call but no one answers. I call Alik and he gives me the address. I go there; they’re doing repairs… what’s going on? Then I call again and he picks up the receiver. And I went over to meet him. Just before this something very interesting happened. Fimka Spivakovskii arrived from Kharkov and says, “We are just sitting here but Riga is going to Israel!” “What are you talking about, what Israel?” I say. “Under Stalin the old people also left; so what? What does Riga have to do with it?” “No,” says Fima, “the Riga OVIR has begun to accept documents! Lida told me.” He was friendly with my friend Lida Slovina, they went to school together and even were together in evacuation during the war. And Fima and I went to OVIR.

We arrived there and it was empty. Empty rooms. Some two people are sitting and requesting to go to Bulgaria. I go up to the little window; a woman is sitting there, as I found out later, it was Akulova. “Your documents!” she asks. “I don’t have any,“ I say. “I came to ask a question.” “Go ahead.” “Tell me, can I submit documents for departure to Israel?” She looks at me, studying… pauses and then says, “You may.” And at that point I became speechless. Incidentally, I became speechless twice with that Akulova: once when I approached her the first time and the second time, four years later, when I came for the visa and this was the last KGB person whom I saw and she shook my hand.

“You may.” I come to my senses. “What do I need for that?” I ask. “An invitation from Israel.” “An invitation from whom?” “Well, it could be from an acquaintance of yours, or from a relative, or from a neighbor….” You hear, that’s how she was talking!!! “So an invitation doesn’t have to be from a mother or father or an immediate relative?” I was thinking, maybe I didn’t hear her right. “No, it’s not obligatory.” “What else do I need besides an invitation?” “You need to assemble many documents,” she said in a business-like manner. “When you start, we’ll tell you everything in detail. They will take your documents but that still does not mean that you will receive an exit visa. After all, you are asking whether you can submit documents for an exit visa. I am telling you that you may.” “Tell me, how long ago did this happen? It wasn’t this way earlier.” I still didn’t believe my ears. “Yes, it’s about two or three weeks,” she says. Amazing! In short, I bow deeply to her and beat it out the door. I come out and Fimka is there. I hugged him and we began to dance on the entrance steps. The policeman standing at the entrance backed off to the side in fright and looked at us as if we were crazy. And the steps were slippery, with an icy glaze…I remember this…I was afraid of knocking Fima over.

That’s it! The next day I go to Khavkin. In his dark communal apartment are his wife Fira, Tina Brodetskaia, the late Marik El’baum, Volodia Baril’, all in socks in order to dance more freely. The music is playing a hora. Khavkin is teaching them a dance. “You teach dances?” “Yes.” “Look, you see,” I say, “people are already leaving and you are teaching dances here.” “Who’s going where?” “Look, yesterday my friend and I were at OVIR…” and I told him the whole story.” That can’t be!” says Khavkin. “That’s what I heard. You can go and check for yourself.” In short, we “sniffed each other out,” exchanged telephone numbers… In a few days I receive a call from him and this time his tone was different…. In time our relations became rather close. We had a small circle of former Prisoners of Zion: Lenia Rutshtein, Meir Gel’fond, Lenia Libkovskii, who always had his guitar and we loved his songs, and Khavkin himself. It was a group of about forty people and it grew. We would get together out of town…on Israel fIndependence Day.

What did you do on an everyday basis?

We engaged in samizdat, printed textbooks, we were very busy organizing ulpans….

How did you produce samizdat?

Producing books of photographs of pages and typing on electric typewriters on thin onionskin paper: we inserted twenty pages at a time and struck the keys as hard as we could. For photocopying we used a rapid developing agent and dried them on newspapers; it all went quickly. Khavkin was a specialist.

How did you solve the problem of our Jewish suspiciousness? After all, you expanded, new people arrived….

A very good question. In Moscow we considered that almost nothing needed to be kept secret. At that time we didn’t even think about it particularly. We worked openly and were not afraid of stool pigeons. It was a feeling that this was our way, our rightness, there was no turning us back…it was an amazing feeling….

Were you in contact with the Hebrew teachers?

Yes, of course.

With Moshe Palkhan?

In our day there was Moshe Palkhan, Khava Mikhailovna.

Mints?

Izrail’ Borisovich Mints… He had lived in Israel…then wound up in Russia because he was a very strong believer in communism… Then, naturally, he served a prison term and when he came out, he was already a normal person.

He loved Israel….

Yes, yes.

And Professor Zand?

Professor Mikhail Zand was then participating in underground activity such as translating and composing samizdat texts in cooperation with Meir Gel’fond.

What kind of texts?

Cultural ones…. I remember that they put out the translation of the book Makor. It combined archaeology with Zionism, a very good publication. Meir had a network of typists and intellectuals working on the texts. It was a powerful samizdat.

They say that he was a very sympathetic person.

Meir was not only a sympathetic person; he also had a golden heart… including with regard to everything connected with health or the hospital. [He was a doctor.] If, God forbid, anyone had a health problem, he was there to help…He was a person full of love, open, lively in a child-like way….a clever person and an acute political commentator.

You rather quickly became a center of Zionist activity in Moscow, Vilia…

That was much later on… It took four years of “slaying dragons” with no end in sight.

A lot of hustle and bustle?

But it was an incredibly intensive life.

Yes….

And this life… it simply drained me completely. I worked, not paying attention to anything and then later, in the end, I felt that I had overstrained myself. It affected my entire future life…. It even hindered me from finding my bearings in Israel…rather strongly hindered.

You weren’t afraid?

There was no fear. On the contrary…. I didn’t have the normal routine life of a Soviet citizen: study, marriage, papa, mama, kindergarten, school, institute, bureaucratic job… I didn’t have this…. Life followed a different course… I was in harness from the time that they came for me at night and took me from my bed…from 1950…. Like Drabkin and Khavkin, I felt that I had to answer for everything, that I had to…who would do it if not I?

A feeling of a mission?

A feeling of a mission, a vocation…Moreover, I don’t even know whether it’s worth mentioning…in Magadan [the site of the forced labor camp] I had a prophetic, mystical dream. I later recounted it to the guys, and people who understand these matters explained it to me… and this also affected me strongly. I felt as if I had been anointed, I was chosen; that was the kind of feeling.

Did you have to present invitations to OVIR or did they suggest submitting documents without them as they did with some activists in the Baltic states?

I received an invitation from Asia Pavlovna, the mother of Romka [Roman] Brakhman, my co-defendant. She said she was my aunt. In Israel they wouldn’t do it any other way; they invariably assigned a degree of kinship. But the KGB knew very well what kind of aunt she was to me. We submitted…there were some comic episodes. They went to look at my wife, who was working at the Institute of Information, as if at an elephant. It was an institute with a lot of dissidents. We all submitted together and in the fall we all received refusals together…over the telephone. That was the form of refusal then—over the telephone.

The reason for the refusal?

For almost everyone it was for “inexpediency.” No one seriously expected any visa. On the other hand, it blew our cover and life began in earnest.

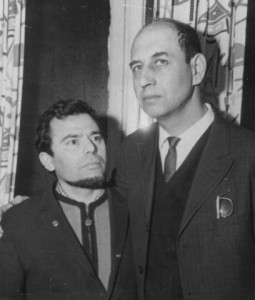

David Drabkin (who, unfortunately, is no longer alive) was six to seven years older than Khavkin and Svechinskii, which was a considerable difference in those years. When I interviewed him (in September 2004), he was in his 82nd year. His family circumstances were difficult, his wife was seriously ill, but I was struck by the young, almost youthful enthusiasm in his eyes, his quick, brisk movements, and way of expressing his thoughts. Drabkin belonged to a rather rare category of early Zionist leaders who never spent time in prison. He came from a highly educated family and successfully engaged in science and invention, combining this with his natural and open Jewish essence.

My parents were educated in Germany and Switzerland before the Revolution, he told me.[18] There was a quota system in Russia then and many went abroad to study. They became doctors of law, worked abroad for several years, and returned to Russia before the Revolution.

Where were they from in Russia?

Mama was from Latvia and father from Ukraine, the Pale of Settlement.

How did they land in Moscow?

During the Civil War my father cooperated with the Soviet regime…he was the chief legal consultant for the Ministry of Heavy Industry. My mother taught in the Institute of Foreign Languages.

Did the family retain some Jewishness?

My mother was from an ancient rabbinical family, her maiden name was Lichtenshtein. In the history of the Jews of Latvia this family can be traced back to the sixteenth century. My uncle was a well-known Jewish actor, a star of the Birobidzhan theater. We were distant relatives of the Yiddish actor Mikhoels. I was acquainted with Jewish artists; we were friendly with Zuskin, Klara Iung… My parents sometimes spoke in Yiddish. Because they had been educated in Germany, there was almost no Russian literature at home. There were the works of Schiller, Goethe, and Heine. As she was from Latvia, my mother was steeped in German culture. Sometimes she would take me to the Jewish Theater in Yiddish.

So you were quite comfortable with your Jewishness?

Yes, no problems. My basic acquaintances were Jews; there were almost no Russians in our home.

Your good connections with the Baltic States were known.

My wife is from the Baltics. She graduated from the biology faculty of Moscow University and I graduated from the Energy Institute in 1948.

You finished the institute at a problematic time….

Yes, they didn’t want to give me a job in Moscow but in the end I managed to find a position at the Moscow Electric Lamp Factory. It was a special factory; an overwhelming number of the product engineers and general drafting directors were Jews.

In 1952 strange things were happening all around.

We, too, were expecting dismissals; in 1953, however, we were expecting deportation. But our director did not want to fire the Jews. He called in sick and stayed in the hospital in the hope that this anti-Jewish wave would subside. He thus sat out Stalin [who died in March 1953], and the Jews in the factory were not fired. When they declared that the doctors [accused in the regime’s contrived Doctors’ Plot] were not guilty, the factory’s director of supplies, a Jew, gathered all of us Jews together and he hugged and kissed us.

When did Israel begin to attract you?

When I was four years old. We were living at a dacha and under us, on the first floor lived a family that suddenly disappeared somewhere. I asked mama where they went and she said that they had left for Palestine and that Palestine was a Jewish land. That was in 1927. I already knew that I was a Jew. And I stored away the idea that if I am a Jew then I should also live in Palestine.

When did you undertake the first practical steps?

When I considered that there was a real chance to leave. This occurred, in essence, after the Six-Day War when someone told me that OVIR was beginning to accept documents. My wife had relatives in Israel, we asked them for an invitation, and as soon as we received it, I went with it to OVIR. But they didn’t accept my documents and began to talk to me. Then we called David and Miriam Garber, who were active Zionists in Riga, and they said that in Riga they had begun to accept documents. Then I went again and that time they accepted the documents.

How did you connect with Moscow Zionist circles?

Someone at work said that I should go to the synagogue on the holiday of Simchat Torah. I am not a religious person but I went. I saw people there behaving in a way that fit my notion of how Zionists should behave. They were singing and dancing Jewish dances. I met David Khavkin there. He brought a tape recorder and played Hebrew recordings at full volume, just three or four meters from the synagogue entrance. The synagogue employee tried to drive him away. I stood next to them and forcefully stepped on the man’s foot. He winced from pain and left. I thus made Khavkin’s acquaintance. He is a straightforward and sincere person and a genuine Zionist, for which he had already spent time in prison. Experienced in dealing with the police and KGB, he was not afraid of them even though they continually hounded him. He would instruct Jews on how to conduct themselves with the police and the KGB and how to behave during a search. He also taught Jews to be proud and not fear anything. Through him I met other Zionists who had served time even before him—Svechinskii and his friends. There were also many from the democratic movement among Svechinskii’s friends. I was afraid of mixing with the democrats because their activity was considered interference in internal Soviet affairs. They arrested people for that. I also met Jews who had been imprisoned for economic crimes—accountants and managers of black market small enterprises…they were also Zionists by inclination.

There was an interesting group that gathered in your factory—Slepak, Pol’skii, Prestin’s wife. I heard a lot about your “tourist packages” [joking reference to those interested in making aliya to Israel].

I organized this group. They came to me because they knew that I was the person who would go to Israel; it was well known, including among the Russians. The Russians thought that even though I was a strange fellow, it was natural for a Jew to try to go to Israel, and they viewed those Jews who didn’t indicate any interest as bad, scheming, selfish and as acting that way because it was to their benefit.

You want to say that for a Russian patriot, Jewish patriotism seems natural?

I think that it’s quite possible that I learned patriotism towards one’s people and country from the Russians.

What did you do in the group?

I read them Tanakh [the Bible]. My approach was based on the Tanakh. “Let my people go,” said Moses. He did not make any demand to change or “democratize” Egypt. He didn’t want anything from Egypt, “Let my people go” and nothing more. I also did not want anything else. But I didn’t say this to them directly…they would not have understood. The second parallel between Egypt and Moscow is the Passover seder. I organized a Passover seder at my home and this became a tradition. We would read the Haggadah, drink the cups of wine…. A huge number of people used to come, the house was full.

Who was included in your group?

Activists of Zionist movement, Moscow, 1969. First row l-r: Nomi Drabkin, Leva Shinkar, Lena Polsky Remes; second row:?, Leonid Libkovsky, Mara Balashinskaya Abramovich, David Drapkin, Sonya Polsky, David Shekhtor, co L.Polsky Remes

Slepak, Libkovskii, Lena Prestina, Pol’skii, with their families. We used to travel together on vacations. Our conversations were on Jewish and Zionist topics.

Did you know Hebrew?

No, I studied it industriously. We would read the Tanakh in Russian. I would clarify some issues with the older men who had studied in a heder. Later I got hold of the textbook for Hebrew study Elef Milim.

I heard that you wrote poetry.

Yes, I did: “I feel alien in this company/ I don’t drink in a threesome/ and I don’t need lard/ and I don’t want cabbage soup.” Or: “the Mediterranean is noisy/ and the wave caresses the shore/auntie strolls along the shore and waits impatiently for me.”

These poems were put to music and the song about the Tel Aviv aunt became popular in our circle. Once near the synagogue I heard the hit song of the year as performed by Louis Armstrong, “Let my people go.” I convinced Libkovskii and Pol’skii to perform this song with a guitar accompaniment. It didn’t go over well in English because our Jews did not know English. Then Libkovskii wrote the words in Russian and the musician Petr Dubrov and my friend Tolia Dukor composed the music. Libkovskii sang it in Russian accompanied by the guitar. This was well received. Later on Dubrov was most savagely beaten up by KGB workers who kept repeating: “Take that for pharaoh.” He was very afraid that they would kill him but I convinced him that if the story reached the West, it would become his defense. Petia agreed and I phoned David Floyd, editor of a Jewish periodical in London whose number I had received from Leah Slovina when she left. This really helped. Dubrov subsequently wrote another song, this time about Jerusalem.

How did you obtain printed material?

Until the break in diplomatic relations [in 1967] we usually would take material from the embassy workers…in the synagogue. Then there was a book fair. There we simply took the books…you could say that we stole them but the Israelis were aware of this and they did not object. Together we managed to translate Exodus; I did it with Pol’skii and Prestin.

Did you know Meir Gel’fond?

Of course. He was very cautious. There was a group there that was connected to Israel and with Nativ.

Did you have links with other cities?

I knew a lot of people from Riga…the Zand family and the Garber family. The Garbers would stay at my place when they came to Moscow. We had a connection with Georgian Jews. Yakov Yakobashvili was one of the outstanding people there. The Georgian Jews were able to sign up a large number of people. Once I complained to Yakobashvili that in Moscow we weren’t able to collect more than a few dozen signatures. He said to me, “I’ll send you at least five hundred and he did. I knew some other Georgian Jews, too—Papatishvili, Menasherov. They would come and stay with me. We had a link with David Chernoglaz in Leningrad—now he is called Maayan—and with Ruth Aleksandrovich in Riga. She would also give me letters….

And how did your letters make it abroad?

Through foreign correspondents. The correspondents were friendly with Yasha Kazakov’s father; they found him interesting. I would ask him when his next meeting would be, then I would come over and hand him the letters. I also utilized the Swiss embassy. It was helpful that my wife knew German so well. A Jew named Yona Etinger, who was a UN translator in Europe, visited me at home. He took a pack of letters and give me the phone number of the Swiss embassy in case it would be necessary to transmit some material. When I had accumulated many letters I would go there. Later I used the channel again and again. That’s what I did without Svechinskii.

You, of course, remember the famous Letter of the Thirty-nine in response to the press conference of “official” Jews in 1970. There were some hot disputes at the time of its signing.

That letter was signed in my home. I was placed first; after that it was easier for others to sign because they trusted me. Chalidze[19] wrote the letter. I opposed mixing together democrats and Zionists. Indeed, my approach was “let my people go.” On a personal level I had nothing against Svechinskii but our approaches were different. He was linked to the democrats and was friendly with Iakir. Of courses that gave him connections but Iakir was too personally harmed by the Soviet regime, which had shot his father. Earlier I had been working in Irkutsk and couldn’t write the letter myself but….after all, everyone in the Jewish national movement ought to be Jews. That’s how it was in Riga and in Leningrad. Why should it be different here?

You didn’t have to live long in refusal…

But I managed to feel it. When a person would submit documents, often his close relatives would cease to have contact with him and he would wind up in the society only of people who thought like himself. The whole application process was accompanied by the loss of acquaintances and relatives. They seemingly ceased to exist for him, they did not invite one any more to birthdays or holidays.

On March 27, 1971 David Drabkin received an exit visa.

[1] samizdat—material that was prepared and disseminated in circumvention of Soviet censorship.

[2] The arrest of these two literary figures in late 1965 was a key event in the development of the dissident movement. Siniavsky and Daniel, who had published works abroad under the pseudonyms of Abram Tertz and Nikolai Arzhak, were charged with “spreading anti-Soviet propaganda.” They were ultimately convicted and sentenced to seven and five years of prison camp respectively.

[3] Schroeter, The Last Exodus, p. 85.

[4] Mikhail Chlenov, interview to the author, January 31, 2004.

[5] Benjamin Pincus, National Rebirth and Reestablishment (Heb.) (The Ben-Gurion Research Center: Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Press, 1993), p. 265.

[6] Vitalii Svechinskii, interview to the author, September 8, 2004.

[7] Schroeter, The Last Exodus, p. 91.

[8] Svechinskii interview.

[9] Lev Mikhailovich Dovator (1903-1941) distinguished cavalry commander in World War II who attained the rank of major general.

[10] Nikolai Berdiaev (1874-1948), noted Russian religious and political philosopher. Originally a Marxist, he rejected the Bolshevik regime and was exiled along with other prominent intellectuals to Europe in September 1922 The above-mentioned work, written in 1937, appeared in English translation in 1955 as The Origin of Russian Communism. Another related work is The Russian Idea (1947). His works were difficult to obtain in the Soviet period.

[11] The above-mentioned were all leading members of the dissident movement. Petr Yakir (1923-1982), the son of the repressed Soviet general Iona Yakir, became a prominent figure in the dissident movement and was involved in the production of the important human rights samizdat journal, Chronicle of Current Events. Arrested along with Viktor Krasin in 1972, Yakir shocked the dissident community by publicly recanting his views and testifying against fellow dissidents. Petr Grigorenko (1907-1987) was a high-ranking army commander who joined the human rights movement in the 1960s. The Soviet regime punished him for his dissident activity not only by stripping him of his titles and benefits but also by sending him to a psychiatric prison hospital for several years. Although Jewish, Il’ia Gabai (1935-1973), an educator and poet, gained prominence for his work in defense of the rights of Crimean Tatars. He was harassed and arrested a few times for his activity. He committed suicide in 1973, a particularly trying period personally and in the history of the dissident movement. Andrei Amalrik (1938-1980), a writer and dissident, is best known for his book Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984? Pavel Litvinov (b. 1940) is the grandson of the noted Soviet foreign minister in the 1930s, Maxim Litvinov. He became involved in human rights groups in the 1960s and was in the small group that protested in Red Square in August 1968 against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslavkia and was subsequently arrested. After a five-year period in exile, Litvinov left the USSR and currently lives in the U.S.

[12] Anatolii Iakobson (1935-1978) was one of the founders of the samizdat journal Chronicle of Current Events. He left for Israel in September 1973 with his wife Maia Ulanovskaia and son Aleksandr.

[13] Bukovskii (b. 1942) was one of the noted cases of those interred in psychiatric institutions in order to silence their dissent. See his memoir To Build a Castle—My Life as a Dissenter (New York, Viking Press, 1979). In 1976 he was exchanged for a Chilean communist and has been living in the West.

[14] Aleksandr (Alik) Ginzburg (1936-2002), Yurii Galanskov (1939-1972), Aleksandr Dobrovol’skii and Vera Lashkova were all arrested for their dissident activity including samizdat publications. Their trial was referred to as The Trial of the Four. Galanskov subsequently died in a prison camp.

[15] Vasil’ev was a Russian dissident who was imprisoned in 1950 for anti-Soviet activity and released in 1956.

[16] Vitalii Svechinskii, “Once More on Tolia Yakobson,” (Russ.) Kaleidoskop (supplement to Vremia), July 24 1992.

[17] Translated from the Yiddish into Russian by Yakov Volfas, a former prisoner of Zion, the novel was published by Mikhail Grinberg (Jerusalem and Moscow: Gesharim, 2004).

[18] David Drabkin, interview to the author, September 8, 2004.

[19] Valerii Chalidze, born in 1938, was active in dissident circles in Moscow in the 1960s-70s and was one of the founding members of the Moscow Human Rights Committee. After he was deprived of Soviet citizenship in 1972 while on a visit to the US, he continued his human rights activities from there.