I returned to Sverdlovsk at the end of May 1971. The investigation into Valerii Kukui’s case had been completed and we tensely awaited the trial. Everyone who had been dismissed from his job but had not received an exit visa needed to find work or else he or she faced the threat of arrest on a charge of parasitism. The procedure was very simple: the district policeman would come, inquire about one’s place of work, and leave a written warning to find work within two weeks.

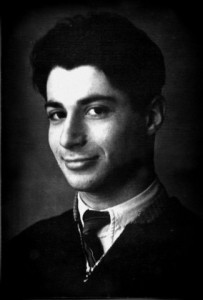

Vladimir Aks, one of the eaurly activist of national revival in Sverdlovsk (today Ekaterinburg), 1970

The wise Volodya Aks had already completed a course for chefs and was working in his new specialty. I found myself in a difficult situation. It was hard enough with a blacklisted identity card to find even simple work without the extra burden of being a Jew, an engineer, and the subject of pejorative comments in the press. Ilia Voitovetskii rescued me.

It was hard not to become friendly with Ilia, whom I met not long before the events described earlier. A fine communication engineer, he was also a poet, and his soul wandered endlessly in verbal thickets, emitting an unceasing stream of aphorisms, jokes, anecdotes, shaggy dog stories, and all kinds of fantasies. A warm and endearing person, he possessed an explosive temperament, incredible physical strength, recklessness, and a weakness for the female sex ─ a kind of Jewish hussar.

“Markman said that the director at the freight rail station is a Jew and they need loaders,” he said. “There they won’t start poking into our work booklets. Let’s try; I, too, left work before applying for an exit visa.”

We were accepted.

The work was not easy. All day one had to transport various loads from the freight cars to the warehouse and from the warehouse to the cars: refrigerators, consumer goods, semi-finished products. We worked in a team of twelve men. As they paid by the brigade, one had to work in coordination. Our muscles ached for the first weeks but, gradually, we became accustomed to it. The loaders, among whom were some good professionals, usually would drink a hundred grams of vodka in the afternoon in order to reduce the tightening of the muscles. We tried it, too, and things were jollier.

In the evenings we continued to meet with friends, discussed the situation, and stayed in contact with Moscow. After Valerii Kukui’s trial we sent numerous petitions to various officials and wrote letters of protest.

Boria Rabinovich received an exit visa and started preparing to leave.

In August two men in civvies picked me up from work and brought me to the KGB. Again Lt. Colonel Pozdniakov. Again a warning with a demand to curtail my activity. And then, unexpectedly:

“Money transfers arrived here from abroad in your name. We presume that as a Soviet citizen you renounce them.”

“Is that a question or a demand?”

“In the meantime, a question.”

“If it’s illegal, send it back and write to the senders, ‘It is against Soviet laws.’ If it’s legal….”

“Then what?”

“Do you really think that I shall insult them by rejecting it? After all, they know that you ruined my life, refused me an exit visa, and had me fired from work and arrested.”

“Now, now, Yuli Mikhailovich, go easy. You ruined your life on your own.”

A week later I received three transfers, each of 150 foreign currency rubles, a large sum at that time. We were immediately dismissed from work. The Jewish director didn’t need visits from THAT organization.

A few weeks later we were already working at a new place, a factory manufacturing electric cables ─ again as loaders. The work was easier and the pay was the same so there were no regrets about the previous place. Here we more often worked as a twosome, which made it possible to talk to our hearts’ content.

At one of our meetings, Volodia Aks drew me aside and asked, “Iliusha didn’t tell you anything?”

“You know very well that he always has something to tell.”

“With regard to Galina Borisovna” (our way of referring to the KGB).

“No, this wasn’t in his repertoire.”

Volodia’s serious look made clear that this was no laughing matter.

“You know, I thought he himself would say something. We promised to be silent but you work together, and I think that you should know. Only don’t tell a soul, o.k.?”

The wise Volodia told me a strange story about Iliusha’s formal agreement to cooperate with the KGB. Ilia immediately informed Markman, Aks, and Rabinovich about this, saying he wasn’t a coward or a traitor but decided that insofar as they wouldn’t let him go anyway (he had a high level of security clearance), at least he could be of some use to us.

“When did this happen?”

“When you were in prison. He himself asked Boria Edelman to inform the appropriate people in Israel.”

Aks spoke calmly and confidently, but on hearing this, I felt goose bumps. I mechanically checked my memory ─ what had we spoken about ? ─ nothing in particular. No, I didn’t think that Ilia had reported our conversations.

“He decided to outsmart the KGB?”

“Something like that,” smiled Volodia sadly, and it was evident that Ilia’s story didn’t afford him particular joy either.

“I can’t…I’ll tell him that I know.”

“Of course, tell him.”

There was no doubt about the sincerity of Ilia’s intentions; he radiated a desire to help. But he was playing a dangerous game. Even telling him that I knew about it meant that, to some degree, I, too, became an accomplice. That’s all I needed!…

On the other hand, how many informers about whom we knew nothing were circulating? Of course, from the very beginning we understood that the KGB would not let us live without its own eyes and ears, and whenever it was truly necessary, we always took this into account.

When I told Ilia that I knew everything, he turned somewhat pale. Despite his hussar swagger, he understood that he had undertaken a risky business. He claimed that it was with the guys’ consent and that he intended to tell me about it soon.

We didn’t go into the details; I personally preferred not to know too much. Ilia merely added that if I wanted to, I could “leak” information via him in the form that I preferred or ascertain what activities of mine were of particular interest to the organs. I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic. My intuition told me to keep as far away from the KGB as possible; otherwise, one could be inadvertently crushed. After all, in essence, we were not their clients. We did not represent any threat to state security: we wanted to leave and nothing more. With this stance one could struggle to leave without being especially apprehensive about informers. The KGB’s goal was clear ─ to destroy the movement, suppress individual initiative, and keep people fearful. The KGB had already demonstrated some of its possibilities so that I had no illusions about them. Once they started to break a person, their talk about the motherland, honor, and dignity was immediately replaced by bared fangs.

Ilia did not make any mistakes: he didn’t betray anyone or cause anyone to be arrested. At the end of 1971 he miraculously received an exit visa, arrived in Israel, and related everything to the appropriate people. In addition, he published several articles about the KGB’s methods. We remained on good terms.

While working on this book, I wanted to delve more deeply into past events. Ilia willingly agreed and began his story:[1]

On March 8 there was a meeting of the physics department at the Ural Polytechnic Institute at which they “worked over” my old friends Volodia Aks and Boria Rabinovich. I happened to be in the institute for work, and, learning of the meeting, I rushed to “the site of the events” and met you, Boria Edelman, and some other guys near the auditorium. You weren’t allowed to enter. From your conversation I learned that on March 9 you were all planning to go to OVIR to apply for exit visas. You immediately pounced upon me, “Do you want to go, too? Come with us.” For a long time I had wanted to go, so I went.

Yes, only two days remained before applying. You without any preparation….

My entire life until then was preparation.

What happened after that?

Not long after that I was sitting with Markman at Aks’ place. Markman, who was often able to predict the course of events, said, “They will undoubtedly recruit someone from our group or they’ll send others. It’s clear that we shall not remain alone; new people will arrive, and we won’t know who they are.” Then he added, “Let’s agree right away. If someone is recruited, we will immediately inform the others.” Two days after he said this, I was summoned and they proposed that I work for them.

When was that?

Soon. We applied on March 10th and they summoned me that month. I remember the time very well because when Boria Edelman left ─ and he left in March ─ I conveyed a message with him to Israel that I had signed a paper with the KGB. We agreed among ourselves that I shouldn’t learn anything that THEY shouldn’t know. That is, I shouldn’t be with you if you were debating something. I should know only the version that THEY were able to know.

Are you sure that no one else was recruited?

How would I know? There were suspicions about some, but let’s not name them now. In any case, I agreed then and was confident that I would not get anyone into trouble simply because we had agreed on the rules of the game. How could I know how I would behave? What if they suddenly would start driving needles under my nails….Therefore it was better for me to know only what THEY could know…. That’s how it went. As soon as I was asked something by the KGB, I immediately told the guys, and at the KGB I could say everything that I knew without apprehension.

You didn’t think that after that they would never let you go?

Aks and Rabinovich said, “Now you’ll never leave.” But I knew anyhow that I would never leave. I had the highest level of secrecy clearance ─ I tested navigational equipment for submarines and also participated in its design and marketing. Perhaps it was a kind of sacrificial game; I was young and ardent and decided to “place myself on the altar” if necessary. Only after arriving in Israel did I find out why I was released, but then it evoked surprise, even disbelief.

Was Pozdniakov in charge of you?

Yes, Pozdniakov himself.

How did he work with you?

I would come at a designated time on the same day of the week to an apartment on the First of May Street. Some old man lived there ─ evidently their former worker or an informer. The apartment had a very spartan room with a cot, a wardrobe, table, and two chairs on which we sat and conversed. There probably was a microphone installed in the wall.

The most interesting part was after the meeting. Nikolai Stepanovich would accompany me out. There was very dense shrubbery in the courtyard and among the bushes was a bench. Here he would talk with me “heart to heart,” unofficially, without listening devices. I don’t know how frank he was; at the time I didn’t believe him but it was interesting all the same. For example, he said to me, “I know that you reset people’s radio dials to different wavelengths so they can listen to the “voices” [forbidden overseas stations] without interference. Do it for me.” “Why?” I asked. “After all, you’re allowed to listen freely.” “No,” he said, “we receive ’tapes‘ with recordings only of those broadcasts that relate directly to our work. All the rest we hear with the same jamming. Please, do it…”

Did you do it?

Of course not. “Look, if I reset it for you,” I said, “then you would arrest me…”

What did Pozdniakov ask you about?

He asked a lot about you.

About me?

About you. Everything that was related to your arrest. They wanted to know what you were capable of doing, to what degree you were prepared to go to extremes. For example, they asked, “Is Kosharovsky capable of committing suicide?” I replied, “If he decides, he won’t tremble.” For some reason precisely this question agitated them the most.

! Once at an interrogation I practically died…I don’t know whether it was me or whether they slipped me something, but they took me away in an ambulance. Pozdniakov was pale and frightened…After all, they also had experienced more than one “purge” and were afraid.

But that wasn’t suicide.

Yes, but I wasn’t afraid, and by that time they had already shown me a lot of their repertoire.

Well, they were concerned precisely about whether or not you would hesitate. But there was no point in speculation about what might have been if…. How could I know? They were afraid of self-immolation or something like that. I remember clearly that I didn’t merely speak but Pozdniakov also asked me to write it down and sign it. They needed to insure themselves ─ they were afraid. I thus wrote, “If Kosharovsky decides, I think he’ll do it.”

Did they ask you about our meetings, our work, or the Hebrew instruction?

There wasn’t any Hebrew instruction then.

Oh, yes! I was teaching from 1969.

I didn’t know. That is, I really knew very little and tried not to take an interest. Too much knowledge brings much sorrow. Yes, so much time has passed since them…. Sometimes they would set a task for me: clarify this or that by the next meeting. I would go primarily to Aks and say, “Vovka, they are interested in such and such.” I would say it and leave ─ so to speak, you knock your brains out over it. Later he would say to me: say such and such, and I said it.

You didn’t sense that they suspected you of playing a double game. After all, you were a Zionist.

Once Pozdniakov said to me, “Ilia, don’t think that we don’t understand anything. We do understand that you….” I was silent and he didn’t elaborate.

Did they try to intimidate you or take you in hand? After all, they always try to break a person even if they project a friendly attitude.

No. Pozdniakov always showed great sympathy.

That’s professional.

The guys agreed to present ourselves as a group that was united on the basis of refusal but was not inimical to the Soviet regime. In general, we took little interest in what was occurring in the Soviet Union.

Yes, that was true for the overwhelming majority of Zionists and for me in particular. And the very process of recruiting informers ─ you couldn’t just simply say: “Yes, I’m ready.” You wouldn’t be believed. They knew that normal people did not like to engage in such matters. They had to pressure you with something, intimidate, or blackmail.

In 1964 I organized a strike at the factory because of an unfair allocation of apartments. The factory and municipal bosses became frightened. After that they dragged me in. Kiliakov, the director of the first [personnel] department [a position usually filled by a KGB officer] said to me in the presence of the KGB supervisor: “Well, did Nikita [Khrushchev] spoil you? Under Stalin your brethren were treated with a firm hand but now ─ you’re given easier work, and your salary is higher, and your apartment is warmer…. Never mind, our time will come. Do you know what I did during the war? I was the head of the special department of the Baltic Fleet! You should only know how many hook noses like you I put up against the wall!” I complained to the chief engineer, with whom I was on good terms, and he halted this case. Then, when I was recruited, Pozdniakov showed me this old “case” ─ a little, gray file with string ─ and said, “If we put this on the prosecutor’s desk, you’ll crash down. No one will pay attention to the fact that six years have passed. There is no statute of limitations with us. So choose: either you sign with us or we put the file on the prosecutor’s desk.”

Was there a streak of adventurism in this terrible experience? Look, I am so intelligent and talented, I’ll outsmart them…

Yes, that, too. As I already said, I was young. It seemed interesting. Both a game and sacrifice ─ I was willing to pass through fire and water for my friends. Everything was sincere. After that, I became very active and wrote collective letters in defense of Kukui and others.

Yes, your letters turned out very well; you’re a writer, a poet.

Once Pozdniakov scolded me: “Ilia, you’re supposed to be our person, but you behave like an inveterate Zionist, you’re too zealous.” “But how could it be otherwise, Nikolai Stepanovich?” I said. “For them to trust me, I have to be like everyone else, but even more so….” He agreed unwillingly and didn’t bother me any more. And the letters went to the West and made it to the “voices”; and THEY recognized my hand. Thus I could do some things with even less risk than you.

For example?

Out of the whole group, only Kukui’s wife Ella and I made it to his trial. I didn’t know him and wasn’t a witness in the case. You were detained in a separate room as witnesses but I sat in the courtroom. Then, after the court session, I wrote out the court protocols from memory. These were also sent to Israel and were read over the Voice of Israel. I went with Ella to Moscow for Valera’s appeal. She managed to enter the courtroom and record everything on a tape recorder. Then I typed it up and the Muscovites dispatched it to the West.

In Moscow I met Sakharov, Chalidze, and Yakir. I often visited in Chalidze’s home and conveyed our Sverdlovsk material and letters to him. Sakharov and Chalidze wrote their protest letters on Kukui’s case based on the details that I provided to them. I prepared considerable material on Kukui’s case for Yakir, who put out the Chronicle of Current Events. Pozdniakov himself later told me that they located me at Yakir’s apartment but he didn’t reproach me further. Perhaps they had some other plans for me. I must admit that all this wasn’t so easy for me. Sometimes I would wake up at night and my heart would palpitate. I didn’t show it, however. Vera kept the phone numbers of Sakharov, Chalidze, and Slepak ─ in case I did not return home from a regular meeting, she could then immediately arouse everyone. After all, in Israel they also knew about me and I hoped that there, too, they would immediately get involved….

Did you work with me as a loader because Pozdniakov advised you to do that?

No, he didn’t suggest that. He knew, of course, that we were working together but he didn’t touch on that topic.

I had the feeling at one time that you were assigned to me as a guard so that I wouldn’t concoct something….

That wasn’t so. I truly worried about you. Indeed, after Kukui was taken, you were the primary candidate for arrest, and you behaved in a challenging manner; it wouldn’t have cost them anything to provoke you. I decided that if I was constantly with you, you would be at least somewhat protected.

How come you were allowed to leave, even with such a high level of security clearance?

I found out in Israel that my release was connected to a scheduled meeting between Brezhnev and Pompidou. The USSR was very interested in good relations with France. At the time they had adopted ─ despite all common sense ─ the French system of color television and the French built the Ostankino TV tower. The prime minister’s office in Israel gave Pompidou’s people a list of eighty families, asking that the French president personally intervene on their behalf with Brezhnev. The list included Volodia Aks, Ella Kukui, and me.

And I wasn’t on it?

Probably not.

Consequently you, with the highest security clearance, left and I, with a lower clearance level, remained behind for another eighteen years.

Well, Yuli, it’s not my fault; I didn’t make up the list…. Yakov Yanai from Nativ pictured the following scene to me. A call comes from Brezhnev’s office to Sverdlovsk, “Do you have this fellow ─ Voitovetskii?” “Yes, but what a security clearance he has!” “What does clearance, you motherf—r, have to do with it! The French president has made a request! Right away, you motherf…r, let him go!” And I already know what happened after that. I was invited to the KGB, or more likely OVIR ─ they were in the same building. Pozdniakov “accidentally” looked in. He shows me a letter from the factory in which the head of the research laboratory division, David Arkadievich Goldring, states his objection to my departure “in connection with…” well, in general, it’s clear. Nikolai Stepanovich asks me, “Ilia, do you agree to write us a letter saying that you don’t possess any secret information and don’t know any state secrets?” “Of course,” I say, “I agree.” They give me a sheet of paper, a pen, an official type kind that you dip into ink, and Nikolai Stepanovich dictates a totally idiotic text to the KGB to the above effect. “Sign. Thank you, you may go.” That was it.

When was that?

It was in October 1971. Some time passed, the game continued, and we would meet at the same apartment. At one of our meetings, Nikolai Stepanovich said to me, “Ilia, I have an important request…. On November 7 [at the time the national holiday of the Bolshevik Revolution], I am on duty in the KGB reception room. Please call me and convey holiday greetings.” “O.K.,” I said, “I’ll do it.” We didn’t have a telephone at home. On the evening of the seventh, I went to a telephone booth and dialed the number. “Nikolai Stepanovich…holiday greetings to you.” In a drunken haze Nikolai Stepanovich mumbles, “Ilia, I want to tell you that in the coming days you will receive joyful news from me. But I have a request. No matter where you are, never forget that were it not for the October Revolution, your Israel wouldn’t even exist. Do you promise that you won’t forget?” “I promise, Nikolai Stepanovich, I promise.” He thus knew on November 7 that I would soon leave.

Did they entrust you with any task when you left?

Vakulenko, the deputy director of the Sverdlovsk region KGB, conversed with me about Bulgakov and Solzhenitsyn. He asked me to be completely frank with him in response to his frankness. “You can be as frank as you want,” I said. “Your frankness corresponds to the general party line whereas mine ─ not exactly” “This is between us, Ilia. The word of a chekist.” “Then,” I said, “you will definitely arrest me.” “Do we really seem so bloodthirsty?” In short, I was lucky and got away with it.

At our last meeting Pozdniakov said to me, “Ilia, you’ll be an Israeli citizen. You must be a loyal citizen of Israel. But don’t forget where you lived, grew up, and received an education. And know that whatever you’ll do, you’ll do it for the good of our country and the good of Israel. Go, get settled, put down roots. When it will be necessary, we’ll find you.” With those words I left.

When you settled down, did anyone try to find you?

We had an agreement about correspondence. I was supposed to write letters to one Rakhil Moiseevna Abramovich at the main post office, poste restante about how I was settling in and everything about myself. I was also supposed to receive letters from this same Rakhil Moiseevna. The first thing that I did….

You went to the Shin Bet [internal Israeli secret police]?

No, after all, they already knew everything in Israel. I was in contact with Boria Edelman and then with Boria Rabinovich. I was met in Vienna by a representative of Nativ and we had a lengthy conversation. … In the context of my work I was acquainted with the report of the Voronezh communication institute for calculating and designing jamming systems for the entire Soviet Union. On the day of my arrival in Israel, Avraam Shifrin found me and said, “Iliusha, the director of Radio Liberty, Max Ralis ─ it seems that was his name ─ is visiting Israel now and will be flying to Paris tomorrow. Can you talk with him today?” Mister Ralis had made a special trip to Israel in order to question repatriates about where and how his station was heard in the USSR. I said, “Avraam, before my departure I had the good fortune to become acquainted with a special report. In short, Max came to our ulpan in Arad and stood by me all night until I wrote down that report from memory. I filled up an entire notebook. That was how I spent my first night in Israel. Later the émigré journal Posev published an article saying that an antenna field was placed on the coast of Spain that significantly improved the reception of Radio Liberty in many regions of the USSR. I was proud: my information was used in this matter. Max and I later spoke about that; he often came to Israel.

Do you feel that you succeeded in outsmarting the KGB in some way?

No. They knew everything. I didn’t betray anyone and, probably, didn’t save anyone. But my intentions were the purest.

Did you feel that they had exact information ─ besides from you?

Not then. Then I had the feeling that I was saving you. But now I see that more likely it was their game and not mine.

Over the years did they leave you in peace?

I described this whole story and published it in Posev with the title “Squealers.” First, Posev published an article that continued in three issues. In the article, which was translated into English, I described the recruitment methods and much else. Of course the KGB couldn’t forgive me for this. After the publication, I received threatening letters: “Our arms are long; we’ll reach you.” In fact, it wasn’t exactly that way. My Rakhil Moiseevna expressed concern in her letters: “Take care of yourself, my dear, after all, you know that they have long arms…” and so forth. A solicitous woman. Someone dropped the letters, which came in typical Soviet envelopes, into my postbox at the entrance to my building without any stamps or postal marks. They thus would demonstrate their omnipresence to me in order to intimidate me. Later the letters stopped coming. For eleven and a half years after my arrival in Israel I never left the country except for one work trip to Europe. Then, in the middle of the 1980s, I began to travel, but each time that I went abroad, I did so in organized groups, and the leader of the group knew that he had to keep an eye on me.

They tried to recruit many people.

It‘s not a matter of recruiting but that one could sign with them and violate the contract.

I never met people who worked for them out of love…. The days of the idealistic chekist were over at the end of the 1930s. Later they would intimidate and force people…. When those people wound up in Israel, with rare exceptions, they would throw off that yoke.

Perhaps, but in my case, this got them very angry. For a long time I couldn’t escape the sensation that, as I was walking along the street, Nikolai Stepanovich was lurking around the corner or at the next stop. This nightmare tormented me for a long time.

I can imagine…. Ilia and the others were very lucky with Mister Pompidou whereas Markman and I remained in Sverdlovsk.

Ilia begged us not to show any joy so as not to attract the evil eye.

Ella Kukui also left. From prison Valera convinced her to do so for the sake of their child. It’s difficult when your friends leave and you are left behind to face the KGB.

THEY tried to make trouble for my younger brother Leonid, who was working as an engineer at a defense factory. He was successfully pursuing a career and he wasn’t yet planning to go to Israel. He was summoned to the first department, where two men in neat black suits immediately explained that they had nothing against Leonid personally. They knew that he was a Soviet man, not involved in anything, and a good worker.

“We would like to talk about your brother. He took the wrong path: Israel, anti-Soviet activity….”

“What?”

“Well, no, meanwhile he isn’t a criminal but he is already on the verge. Help keep him from the dangers that could end very badly for him, and this…this would also reflect poorly on you.”

Leonid is not the shy type.

“In general, he doesn’t consult with me,” he said. “We live apart; each has his own family, but have no doubts: if I see that he is planning to do something illegal, I’ll tell him. You have nothing to worry about.”

“But, perhaps you could….”

“No, I couldn’t.”

They kept returning to him again and again and he would say:

“If I see something wrong, I’ll tell him. I won’t spy on my brother and all the more so, I won’t inform on him.”

“Well, we counted on greater understanding on your part. You will feel this.”

And he did feel it. A year later he had to leave his job. Ten years later I asked him why he hadn’t applied for an exit visa because so many years had passed after his work with security clearance. He smiled and said, “After they allow you to leave.”

“Why, then, did you leave that work so early?”

He then told me the above story.

THEY tried to make trouble for my wife. We were formally divorced because otherwise they would not have accepted my documents for an exit visa.[2] This time they received a categorical reply: “I won’t spy on my own husband!”

They kept a close watch on me as before. Sometimes I was detained and threatened. Over time I developed an instinctive reaction to them: I could feel their presence with my back…. And I began to sense danger like an animal.

There were few new people but occasionally some appeared and they would seek to meet me under the impression of the newspaper articles. Among them was an attractive couple, Mark and Anya Levin.

We continued to prepare for the court hearing of Valerii Kukui’s appeal, sending letter after letter to various officials. We felt that our letter to KGB chairman Yuri Andropov produced a strong impression. We ended it like the group letter of the Georgian Jews with the words: “Israel or death.”

I was detained on the street and brought to the police station, where two KGB officers were waiting for me.

“Our patience is exhausted. We have more than enough material on you…. You’ll rot in prison. This is our last warning; we won’t talk to you again!”

Then in a more peaceful tone: “It seems like you don’t know how to draw the necessary conclusions…. We would be happy to toss you out of the country but your missile institute categorically objects. You won’t receive a visa in the coming years; don’t even try, and with such behavior ─ only prison lies in your future.”

This time it was serious: I felt it with my back. I consulted with Aks, who was supposed to leave in a few days.

“Look,” he said, [3] “this whole region is full of security-related enterprises, the KGB is fierce, and it goes overboard in protecting itself. Perhaps it’s worth trying for a visa from another place. Indeed, at the beginning we thought of applying from someplace in the Baltics or from Georgia, where there are no security enterprises and the atmosphere is different. Eitan Finkelstein moved to Vilnius precisely for this purpose.”

Volodia Markman had a different opinion: “They’ll get you wherever you are. Here, at least you have friends and relatives. You have to try to break through from here.”

When I shared Aks’s idea with the family, mama immediately seized upon it. To my surprise, my wife also did not object. I decided to try from Georgia. We discovered a distant relative living near Tbilisi who was ready to host me in the beginning.

After parting with Aks a week later, a train sped me to Georgia. My route took me to Moscow, where I knew only three names: Slepak, Polskii, and Prestin, the new leaders of the Moscow refuseniks. I had not met them personally and I was happy at the opportunity get acquainted.

Polskii was very businesslike: he inquired about matters in Sverdlovsk and asked me to drop in before my departure ─ perhaps he would transmit something to Kiev or Tbilisi.

Slepak received me in a warm, friendly way. People would flock to his apartment, coming and going all the time. Someone was whispering in the kitchen and partially filled tea mugs and an unfinished cake was in evidence on the table…. Volodia asked about our Sverdlovsk affairs and immediately introduced me to someone. He reacted unexpectedly to the idea of getting out via Georgia:

“You have no secrets from them; you will stand out there like a very noticeable black sheep. It might become even worse. Stay in Moscow. We have plenty of people like you here. Together it will be quicker and more reliable.”

He told me about his first level of security clearance and gave some other examples.

“Who will give me a residence permit for Moscow? The city is closed to ordinary people and with my record!”

Volodia smiled. “You underestimate us. Go and stroll around until the evening and then we’ll see.”

When I returned, he already had an alternative. He found a girl for a fictitious marriage so that I could register in Moscow. She also planned to emigrate.

The following evening I was introduced to a charming girl named Nora who didn’t nix the idea. We applied at the marriage registration office [the Russian acronym is ZAGS] and the marriage was registered in a month. A month later we applied for an exit visa and were rejected. Thus began my Moscow refusenik life, which continued for a long seventeen years. In a year and a half, Nora received a visa; the marriage of convenience ended, and she left. [4]

Despite the absence of relatives and the lack of a normal living arrangement, life in Moscow turned out to be easier and more pleasant than in Sverdlovsk. People were open, sociable, and friendly.

On the Sabbath a kind of “refusenik club” used to gather on the hillock near the central Moscow synagogue. There one could learn the latest news; meet people; arrange to go to farewell gatherings for those who were leaving; order invitations from Israel; find Hebrew teachers; and meet with tourists and foreign correspondents.

On this hillock I made my first Moscow acquaintances.

Valera Korenblit, who knew everything that happened among refuseniks, generously invited me to live in his one-room apartment for a few days. He lived in that room with his wife and daughter and in the little kitchen was a trestle bed, just for me.

Valera acquainted me with Zhenia Epstein, a weight lifting trainer of the Trud sport organization. Although educated as a chemical technician, Zhenia loved sport, completed the training, and changed profession. A week after we met, Zhenia received the keys from a cooperative apartment, but he didn’t plan to move there right away.

“If you want, go live there,” he offered. “Only keep in mind that it is empty and without a telephone.”

The offer was generous. I didn’t have any personal belongings ─ only a briefcase that served as a pillow. My coat served as bedding or a blanket. After a few weeks I bought a cot and felt completely comfortable.

Later Boria Tsitlenok took me in. His relatives obtained exit visas and left, but he received a refusal and remained alone in a two-room apartment. A most kind fellow, he selflessly participated in all the demonstrations. Nora then acquainted me with a friend who, like Zhenia Epstein, had received the keys to a cooperative apartment but was in no hurry to move, and I settled down there.

It didn’t occur to me to try to find a more or less fixed residence. The ranks of the departing constantly grew, many veteran activists received exit visas, and refusenik life seethed in expectation of a breakthrough.

About the time of my arrival in Moscow, the change in leadership of the movement was completed. The founding fathers ─ Khavkin, Svechinskii, Gelfond, and also Drabkin and the members of the All-Union Coordinating Committee from other cities who were still at liberty ─ left the Soviet Union by around March 1971. Misha Zand left in the summer. At the end of 1971, Vladimir Rosenblum, Pavel Goldstein, Mikhail Margulis, and Vladimir Zaretskii emigrated.

The new leaders were not newcomers to the movement, having shown their colors during the wave of trials in the 1970s, at the Brussels Conference, and at summits in Moscow and Canada. They were experienced in organizing successful actions such as the numerous collective protests at the Central Telegraph office or in the reception rooms of highly-placed officials that frequently ended with fines or fifteen-day arrests. They were involved in the composition of numerous personal and collective letters, petitions, and appeals, which were signed openly on Saturdays near the synagogue ─ sometimes several letters a day.

Later I often heard that the aliya struggle was conducted by a small group of selfless refuseniks, but this assertion is not true. The movement had a broad social base that included hundreds of thousands of people who listened at night to Kol Yisrael and the broadcasts of other “voices,” tens of thousands who sought an opportunity to leave, and many thousands involved in the process of applying for exit visas. They comprised the breeding ground for the movement. The refuseniks simply stood on the front line of the struggle.

The movement that I saw in Moscow in 1972 appeared mature, with a ramified network of domestic and foreign links, mutual help, and a group of representative leaders. Although there was no formal leadership or external signs of an organization, some people stood out in terms of their activity, knowledgeability, and authority. In addition to their work in organizing life in refusal, the activists supported an effective link with the Jewish world, receiving foreign politicians and public figures. It was a special world, struggling for the right to leave and for survival.

[1] Ilia Voitovetskii, interview to author, May 27, 2004.

[2] Yuli’s wife Sonya couldn’t go with him because at the time she needed to take care of her elderly, ill mother.

[3] Vladimir Aks, interview to author, May 23, 2004.

[4] Nora was told by the authorities that she had to divorce Yuli in order to obtain an exit visa. After her departure, Yuli was able legally to live in her former apartment.