On March 20, 1973 the Politburo discussed the education tax in the context of General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev’s upcoming visit to the United States. Because of the strong criticism that the tax evoked in the West, Brezhnev even proposed suspending it, at least until the completion of his visit. Justifying the KGB’s slow response to Brezhnev’s orders, Andropov complained: “We are now receiving applications even from academicians,” and, addressing Brezhnev, he added “I gave you a list.”[1] “Not from academicians,” retorted Brezhnev sharply, but he demanded a halt to the tax.

Under the prevalent Soviet policy on emigration, academicians with advanced degrees were being refused exit visas and losing their jobs and the opportunity to engage in scientific activity.

The stream of academics enhanced the prestige of the movement. Needing their own niche, however, whereby they could not only maintain their scientific level and remain in contact with colleagues but also utilize their collective potential for the aliya struggle, the scientists established a system of refusenik scientific seminars. Professors Aleksandr Voronel and Aleksandr Lerner were among the founders of this system.

Mark Azbel wrote:[2]

Voronel gave considerable thought to the type of problems that scientists of our level would encounter after they had been expelled from laboratories and institutes and became out of touch with their fields of research. Scientific ideas develop so quickly and are nourished by so many discoveries and new decisions that being cut off from this stream could lead to intellectual starvation…. When Voronel first proposed the idea of a seminar, many did not approve. “We are struggling for the freedom to escape from here,” opponents objected. “People are organizing protest demonstrations and sending petitions to international organizations. You can’t stop this and busy yourself with physics.” But Voronel, I, and several other scientists tried to keep up our professional level and at the same time participate in the general collective struggle as a fighting unit, maintaining contact with colleagues abroad and trying to obtain their support.

“In the summer of 1972,” wrote Aleksandr Lerner in his memoirs,[3] “it became obvious that the authorities had no intention of freeing Refuseniks soon, especially those highly skilled in professions. We would have to prepare for a new way of life, for a long siege. This promptly raised several problems. How are we to live when we were dismissed, with no hope of finding new work? How were we to keep abreast of developments in our fields while totally excluded from scientific endeavor?”

Jews constituted a significant sector of the Soviet scientific elite. To them, seminars represented a natural and customary form of scientific activity. The unusual aspect was that this was a gathering of refuseniks, society’s outcasts who were under continual KGB surveillance, and it was not clear how the punitive organs would react to this new form of refusenik activity. Previous experience was not encouraging: the KGB principle of “divide and conquer” that sowed mutual suspicion within Soviet society was applied to an even greater degree toward its ideological opponents, the Zionists.

In the light of the recent wave of anti-Zionist arrests that had fanned across the Soviet Union, the KGB reacted nervously to any form of refusenik activity, especially one in which the best and most educated minds of that community gathered together. It thus meant that one had to appraise possibilities carefully before undertaking something new. Aleksandr Voronel was the first to tread on this thin ice with his seminar under the official title “Collective Phenomena,” which began to operate in April 1972. Because of the basic role of physicists in this seminar, in refusenik circles it was referred to as the physics seminar.

A few months later, in the summer of 1972, Aleksandr Lerner’s seminar devoted to control systems and the application of mathematical methods to medicine and biology was opened. We called it the cybernetics seminar. In the fall of 1972 Vitalii Rubin’s humanities seminar began to operate. A year later I organized the engineering seminar. In time, others cities and refuseniks groups (Hebrew teachers, historians, and religious groups) seized upon this initiative.

Voronel’s Seminar

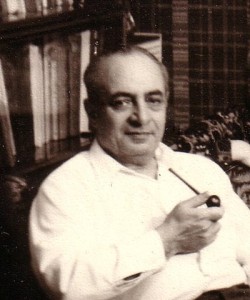

Aleksandr Voronel (b. 1931), a professor of physical mathematics, spent about three years in refusal. During that time he organized the first scientific seminar and directed it, facilitated the establishment of a humanities seminar in which he also participated, was a founder of the impressive refusenik journal Jews in the USSR (Evrei v SSSR), and became the chief editor of that samizdat journal. Voronel’s initiatives, which were distinguished by their quality and stability, continued to function effectively after his departure practically until the fall of the Iron Curtain, and they played an important role in the Zionist movement. Always smiling and good-natured, with a natural social talent, he gave the impression of a lucky person, born with a silver spoon in his mouth. I don’t know how he managed to create such an appearance because, in reality, his life was very different.

“It’s my nature; now, too, I always smile,” he said to me during our interview. Sasha Voronel grew up practically without a father; at age fourteen he was arrested for anti-Soviet activity (pasting up leaflets in a workers’ settlement) and sentenced to three years in a work camp for youth.

How did this happen? I asked him.[4]

My mother left my father when I was six years old. She went from Leningrad, where I was born, to Kharkov, where she began studies at the history faculty of the local university. Together with her and her student friends, I surveyed the entire history of mankind, which, apparently, inclined me toward the humanities. During the war we lived in evacuation in Cheliabinsk. In 1945-46 the situation there was terrible. People were dying from hunger and war invalids were begging on the streets. At the same time, if one had a lot of money, it was possible to buy everything at the commercial stores. I did well in my studies and was friendly with boys from elite families, for example, the son of a factory director. When we would go to his home for birthday parties, it was a nightmare. They would serve soda! And we thought that only the state could sell and serve soda. Or they would show a movie! Movies, indeed, were a state monopoly. We viewed this as the corruption of the Soviet leadership. The picture of inhuman suffering against the background of abundance for the wealthy ignited “the fire of the class struggle” in my youthful heart. I used to discuss this ardently with a group of boys. The father of one of them had been repressed in 1937. He had a rich library with books that were printed before the communists learned to excise the problematic spots. There we would read Lenin in a 1929 edition in which he expounded on Marxist science; it was accompanied, however, by Axelrod’s remark that this was a mediocre philosophy and, in fact, things were much more complex. Or else Lenin would roundly criticize the workers’ opposition and the notes would append the programs of the workers’ opposition, which were naive but truly communist programs. In general, we acquired a revolutionary spirit from these books and understood that the revolution had taken the wrong path. We decided to disseminate this knowledge in the workers’ settlement of the Cheliabinsk tractor factory. We pasted up leaflets…several times (!) calling on the workers to fight against the bureaucracy and injustice.

And you were caught.

Our group consisted of seven youths, all Jews. The KGB treated us rather humanely; they released all of us except for two. As I was a fourteen-year old minor, I received three years in a youth colony.

And did you get the full treatment in the colony?

The colony was made up mainly of boys aged fourteen to sixteen from PTU (a manufacturing-technical school, a semi-closed educational institution that was part of the “Workers’ Reserves” system, Yu. K.). They were arrested for fleeing work and running home. That was considered sabotage for which sentences from one to three years were handed out. They were immature, weak boys, easily dominated by hooligans, which the administration supported. The criminal element ruled, forcing the lads to work while assuring the absence of any extraordinary events, and the administration turned a blind eye to the fact that the criminals ate half the rations. That was the alliance. I got by the best I could. I pretended, for example, that I was an artist, and the criminals had major esthetic requests. They demanded that I decorate the barracks and write slogans. I arranged for my co-defendant to accompany me, saying that he took care of the paints. Nevertheless, it was very difficult: there were fights, they would taunt us, and there was good reason for revenge, but it was not accepted among the boys to complain. I might not have survived until the end of my term but I was released early, after half a year. This was the result of a new decision by the Supreme Court according to which minors could receive a suspended sentence, and my future stepfather, a front line soldier, interceded on my behalf. After my release, my relatives categorically declared that in the future I would study only physics, mathematics, or something similar. My father, Vladimir Poliakov, perished at the front. My stepfather adopted me and my name became Voronel. Poliakov disappeared. When I left the colony, I began to take part in sport, understanding that it was necessary.

How did the “tremor of Judaic anxieties”[5] awaken in you?

I was so attracted to science that I forgot about my humanitarian pursuits. Then, after the Six-Day War, the Poles demanded that the Jews swear loyalty to Poland or leave. And I began to think that in Russia, too, we must decide this issue for ourselves: either we are Russians or we are Jews. Until then, the question hadn’t occurred to me. And just then the Leningrad Trial came up. I decided that, ultimately, I was a Jew, became spiritually liberated, and began to read literature.

When did you decide to leave?

In March1971, asmall group of Moscow refuseniks received exit visas ─ activists with whom I was friendly such as Meir Gelfond and his circle. I asked him to send me an invitation from Israel. He sent it five times but I didn’t receive it. A year later, in January 1972, Viktor Yakhot went into the Dutch embassy, requested and obtained a state invitation [entry visa] for me. After that, I started to receive the invitations ─ all five of them.

How did the idea for the seminar arise?

I gave a lot of thought to the fate of the scientists. I saw how my colleagues suffered from the systematic refusal to let them leave. Some said that what they feared most of all was losing touch with their discipline and with scientific colleagues. The scientists came from different fields, but I was always inclined toward interdisciplinary thinking and thought it would be a good idea if each person acquainted the others with his or her work in terms that would be comprehensible to all academics even if they were not specialists in that field.

What was your assessment of the degree of danger in this initiative? After all, you intended to bring together refusenik social outcasts, Zionists, ideological enemies of the regime.

I thought about it and consulted with Chalidze. Poring over the criminal codex of the RSFSR together, we found that no scientific activity could be prohibited in the Soviet Union.

After Chalidze you went to Lerner?

To Lerner and Levich.

Veniamin Levich had already applied for a visa?

No, but I heard via third parties that he was considering it. I knew him as an outstanding physicist. We even shared some interests. Levich questioned me in detail: “Sasha, were you ever dragged into the KGB?” “Yes,” I said. “They don’t beat, do they?” He was afraid. But Lerner didn’t ask; he was more informed than I was.

With regard to aliya?

About everything. He said, “I have been abroad twenty-six times. I know that they won’t let me leave so simply, that I must prepare for a long period of refusal, but I am confident that it is worth the risk. In another decade or so everything here will collapse” ─ he said that in September 1971! “And who will be blamed? We, of course.”

Despite its usefulness for scientists, the idea of a seminar at that time did not seem so convincing.

Yes, I argued about this with Polskii. He said, “Our cause is Zionism; we should leave and that’s all.” Later on, however, he saw that it was successful and joined in. Incidentally, at first he also didn’t approve of samizdat. He said that it reminded him of the democrats’ human rights struggle. I objected: “No, we must first identify ourselves as a separate group, let’s say ethnic or social, and declare that these are our normal living conditions. If these conditions don’t suit the Soviet authorities, that’s their problem, and ultimately they’ll have to realize that their case is hopeless.” This was, of course, an optimistic statement but it worked to a certain degree because within this logic they couldn’t offer any arguments. I was frequently dragged to the KGB, especially before the international seminar in 1974, occasionally a few times a day. They tried to intimidate us but I saw that they didn’t have a clear legal basis for their position.

You initiated the seminar and let them use your apartment. In parallel you founded a practically open samizdat journal [Jews in the USSR] with the names of the editors and contributors on the cover. After a youth like yours, wasn’t that reckless?

Probably, but I myself didn’t feel it. Essentially, we had to lead our life in a way that would antagonize the authorities as little as possible but at the same time was completely unacceptable to them. We had to behave in such a way that the Soviet regime would want to get rid of us. This entailed a certain risk. As you know, the regime violated the laws when it considered it necessary. I was publishing samizdat, I was being dragged to interrogations at the KGB, where they would say something and threaten me but not once was I charged with anti-Soviet behavior. Yet, when it suited them, they accused Brailovskii of anti-Soviet behavior for doing the same thing.

Brailovskii was arrested in 1980, when the political circumstances had changed.

I understood that it was a dangerous balancing act, but I think it was the sole option.

As far as I know, at first people, didn’t rush to take part in the work of the seminar or journal.

Yes, but afterwards, everybody wanted their name on the cover.

Well, that was after the basic risky part was already behind and powerful international support materialized; participation could serve as an element of a springboard for aliya.

At first, I didn’t even dream of the grandiose support that we received, although I had hoped, of course, for some kind of backing. Before applying for an exit visa, Azbel and I met at an official international symposium in Leningrad with two Western scientists. Each of them promised support in his own way. They represented two opposing approaches that always co-existed in the Jewish movement. Pierre Hochenberg immediately grasped the matter and said he would go anywhere and speak with whomever it was necessary. He talked to Yuval Neeman, who spoke with Nehemiah Levanon. The other scientist believed in the value of secret diplomacy. He said that he would speak with Kissinger and someone else but all this led nowhere. He wanted to act individually, without the Committee of Concerned Scientists.[6] At first, we hoped that Jews would support us, perhaps some scientists also, but it turned into such a powerful and fashionable form of solidarity that people simply flocked to us. People from India, France, and so forth arrived….

Attending your seminar guaranteed them broad publicity.

That was a possibility, for which we must thank Nehemiah Levanon; he, and of course Yuval Neeman, backed us with their authority.

Were you in contact with the Liaison Bureau?

No. I met Levanon only in Israel.

Nehemiah loved you.

Yes, and I also loved him. I saw, of course, that he was a gangster, but I liked that kind of gangster. It seems to me that one needs to be a gangster in that underground politics.

The arrival of important scientists was probably not just a matter of solidarity. What was the scientific level of the seminar?

The main task was not to impress professionals with the achievements in one’s narrow field but to try to make one’s field and ideas accessible to a broader scientific circle. In most cases this was accomplished successfully and I am proud of it.

You and Mark Azbel were old friends from Kharkov. Did he lead the seminar in your presence?

He conducted the seminar after my departure. I always led them myself. Among scientists, as among writers, there are many ambitious people who eagerly put each other down. Sometimes I had to restrain them and correct matters. … Several times Mark told me later on the phone that it was a very difficult school of social behavior for him.

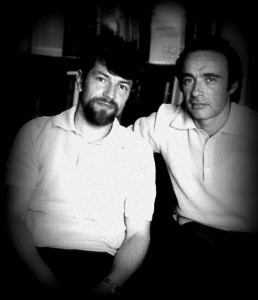

At first, eight people took part in the work of the seminar at Voronel’s apartment: Voronel himself, Mark Azbel, Irina and Viktor Brailovskii, Dan Roginskii, Viktor Mandeltsveig, Moshe Gitterman, and Veniamin Fain. In time, the composition of the group expanded considerably and numbered over twenty people. After Voronel’s departure in December 1974, Mark Azbel headed the seminar.

How did you manage for so many years to stick to purely scientific topics with people who were focused on leaving the country? I asked Mark.[7]

It was my conviction. I knew exactly what I was doing and why. Before each session, I categorically declared that during the seminar nothing other than scientific matters would be discussed. From start to finish, questions such as “who are we, where are we, how are we” were not permitted. The start and conclusion of a seminar were always announced. It’s true that I didn’t interfere if people conversed quietly among themselves in the room. Yes, we worked in various fields of physics but the discussion on the level of ideas did not require going into complex details and didn’t lower the level of discussion. We wanted to know about everything of interest in any scientific field. The program of our colloquium most frequently touched on some area of physics but there were also reports on biology and economics. We discussed current and future aspects of science.

Did foreign scientists visit you?

At first, guests came to support us in our troubles, but they left very favorably impressed by the seminar, especially because no one complained about his or her problems, only in response to direct questions. They were astonished that, indeed, we were conducting a purely scientific seminar. The result was fantastic. Nobel Prize winners were our guests!

Were your guests only Jewish scientists?

For sure there were also non-Jewish scientists. It’s also true that the majority were Jews. We never asked. Usually the guests were on a very high level, people who were invited everywhere but usually accepted only one invitation out of ten or twenty. The word was out….

Were refusenik matters discussed after the session?

Usually after the end of the official part, some people left ─ after all, we weren’t all refuseniks ─ and some stayed. Liusia always served tea and something with it ─ not shashlik, you understand.

Those who remained were free to talk about any topic. I merely warned: “Speak freely, but keep in mind that we have a KGB presence in the room recording everything on tape.” We therefore frequently used children’s “magic slates”. Do you remember them? You wrote on the plastic and when you lifted it up from the waxed board, the writing disappeared.

You participated in the seminar from the time it was established, I mentioned to Dan Roginskii.[8] At the same time you were teaching Hebrew and you had a phone link to Israel. How did you find time for all this?

Indeed, my life was exceedingly full. The high point before my departure was the hunger strike of seven scientists in June 1973. I had frequently participated in short hunger strikes but only one was very long. It lasted two weeks and evoked a great resonance in the West and Israel. The chief rabbi of Israel, Shlomo Goren, phoned and said that one shouldn’t fast on the Sabbath because this was against the Halakhah (Jewish legal code). We discussed the matter at a meeting and, in our second conversation with the rabbi, we succeeded in convincing him that we had to continue. We then continued our fast at Lunts’ apartment for another seven days. The telephone, which fortunately was not disconnected, didn’t cease ringing. The formal reason for our refusals was secrecy considerations but, in truth, it was not applicable in our cases. Three months after the hunger strike, I received an exit visa and I think this played a role. But the movement as a whole played an even larger role.

Who took part in the hunger strike?

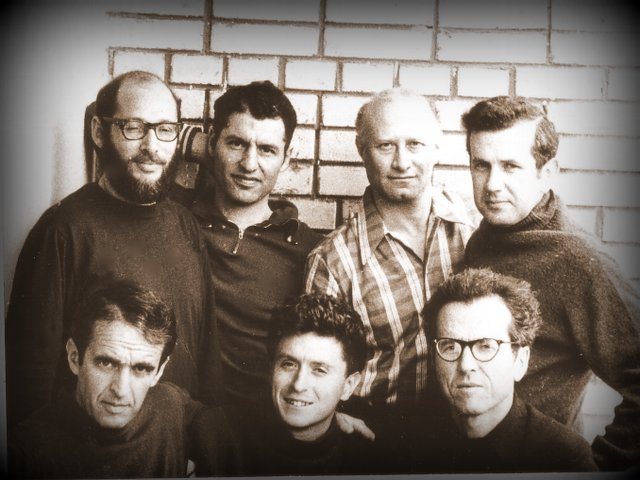

Azbel, Voronel, Gitterman, Lunts, Brailovskii, Roginskii, and Libgober. Libgober received an exit visa during the hunger strike.

Partcsipants of scientists’ hunger strike l-r fist row: Alexander Lunts, Natan Libgober, Moshe Gitterman; second row: Dan Roginsky, Alexander Voronel Mark Azbel, Victor Brailovsky, Moscow, June1973, co D. Roginsky

The hunger strike started on June 10, 1973. It was carefully planned and thought out. There was a reason for the timing: “General Secretary Brezhnev was about to leave for the United States and we wanted to ensure that he would be met with as many difficult questions as possible,” wrote Azbel.[9] “Our friend Emil Liuboshits had just received his exit visa and would be in Israel by the 10th. … He was supposed to be our chief representative in the free world. … He would contact the press and would spread the news of what we were doing among those who would understand the significance of the demonstrations, first of all to Professor Yuval Neeman.”[10]

Before the hunger strike, four participants ─ Lunts, Roginskii, Libgober, and Brailovskii managed to take part in a protest demonstration on Arbat street in the very heart of Moscow. They carried placards demanding freedom of emigration and were detained for a few hours in a police station, thus almost missing the start of the hunger strike. According to Azbel:

Since we had told nobody at all of the hunger strike, it came as an absolute surprise to the KGB. They had no time to take any measures to suppress this action. The KGB is very effective when it is carrying out scheduled plans, but if anything unexpected happens, if there is any element of surprise, it requires an interval before it can react. … No one in the ranks wants to risk his position by taking unauthorized responsibility or making a move without specific instructions. So, for a while, the authorities refrained from interfering with us.[11]

In its report of the hunger strike, Reuters cited Azbel’s declaration: “We don’t want to die. We want to live and work in Israel. But we prefer to die than live here as slaves.”[12]

The most essential and time-consuming of our activities was to answer the hundreds of telephone calls that poured in on us from all over the world. We had several days of calls before the KGB actually realized what was happening, whereupon our line went dead. But after only about an hour, during which the constant ringing stopped, it started up again. We heard that so many of our callers from abroad had expressed furious indignation at this suspension of our service that the authorities had felt it politic to reconnect the line. An astounding victory![13]

Western correspondents also visited the hunger strikers and conducted numerous interviews. Western scientists expressed strong support, protesting to Soviet authorities and in some places they even started hunger strikes in solidarity. According to the June 20 issue of the Israeli newspaper Davar, thirty instructors in the Haifa Technion conducted a hunger strike in solidarity with their Moscow colleagues. They concluded their hunger strike after the end of Brezhnev’s visit. It had accomplished its task of presenting Soviet emigration policy in its true light at a moment of important high level talks.

The seminar’s next large project was the holding of an international scientific symposium. Professor Moshe Gitterman, who received permission to emigrate in September 1973, informed people in Israel about the idea. The chosen topic of the symposium was the application of physics and math to other branches of science. Emphasizing the exclusively scientific nature of the international symposium, the initiators ruled out any political aspects to the reports. They were aware, however, that the very act of conducting an international symposium that was not officially sanctioned was an unheard of challenge.

“Starting in January, Sasha Voronel, Viktor Brailovskii, and I began to dedicate all our energies to planning this symposium,” wrote Azbel. We decided to hold it from July 1 through 5, 1974.”[14] An International Organizing Committee was set up that appealed to the international scientific community to participate in the symposium.

Amazingly, the dates for the symposium coincided with the visit of President Richard Nixon to the USSR, I noted to Mark Azbel.[15]

This coincidence became a dangerous complication for us. Although Nixon’s visit was announced much earlier, the exact date was not reported. Once the date became known, our idea acquired the appearance of a planned protest or provocation. We even discussed changing the date to a later time but, ultimately, we decided that it was unrealistic to ask Western scientists to change their long-term plans that they had made much earlier. Admittedly, in 1973-74, we still had a very vague notion about the situation abroad. In planning the symposium, we didn’t seriously consider that something major would develop out of it. Both we and the KGB learned with great astonishment about the formation of foreign committees in support of the symposium. It occurred without our urging.

I have in my hands an open letter of January 24, 1974 to the worldwide scientific community, that is, at the height of preparations for the symposium. The letter was signed by Mark Azbel, Aleksandr Lerner, Aleksandr Voronel, David Azbel, Veniamin Levich, Aleksandr Lunts, Viktor Brailovskii, Viktor Polskii, and other refusenik scientists. In it you describe the harassment of scientists and try to mobilize international support for them.

Those are different matters. There’s no doubt that we did yell at the top of our voices: “Fellow scientists, help us!” It was a cry that was not directed at anyone in particular. Our plans, however, led to completely unexpected results; it turned out to be something much larger than we had assumed it would be. Do you think that we could imagine that support committees would be formed in the West? After all, you also come from the USSR.

Of course, and, therefore, it seems to me that the symposium was designed to have a purely scientific format so that disrupting it would be most uncomfortable for the authorities and thus have a greater effect. But, do you agree, Mark, that this was an unimaginable challenge to a totalitarian regime?

There’s no doubt that we acted like kamikaze, teasing a mad dog and hitting it on the nose with a stick. You yourself recall that situation. It’s true that we shouted loudly, but we couldn’t comprehend the degree of reaction from the outside. Our choice of dates was absolutely innocent ─ the symposium was planned for the summer, when scientists have a vacation. They could say that during their private vacation, they came to the symposium, where they heard only scientific reports. What politics was involved? For Western scientists, politics was “not kosher,” which is why we turned to them as scientists to scientists. Under no circumstances did I involve them in our politics. This first international seminar of 1974 failed, but at the second (three years later), the Academy of Sciences was beside itself with annoyance and envy. There had never before been such a conference in the USSR. We didn’t imagine that the scientists would be on such a high level that the KGB couldn’t refuse them. The KGB intimidated them and warned them but didn’t dare to do anything and they arrived.

The preparations for the first international seminar encountered serious difficulties. As early as April, the newspapers Trud and Sovetskaia Rossiia reported that Tel Aviv University was planning to conduct a session in Moscow but permission would not be given for this. This served as a warning to the organizing committee. At the beginning of May, the authorities began disconnecting the participants’ phones and blocking their postal connections abroad. Even conversations from public telephones were interrupted. The foreign visitors did not receive entry visas, members of the organizing committee were arrested until the end of Nixon’s visit, and their wives were subject to house arrest. The police set up surveillance posts at the entrances to the buildings and next to the apartment doors to make sure that no one entered or left the apartments. The first international seminar was thus disrupted. The organizing committee received 150 reports, thirty from Soviet scientists, including Academician Andrei Sakharov and corresponding member of the Academy Yuri Orlov, and over 120 from the U.S., England, France, Israel, and other countries. The would-be participants were world-renowned scientists including Nobel Prize winners.

The next international symposium was planned for three years later, on April 17, 1977, the fifth anniversary of the establishment of the physics seminar. It was held very successfully despite the regime’s pressure and spy mania that recalled the poisonous Stalinist doctor’s plot campaign. It took place around the time of the arrest of Anatolii (Natan) Sharansky, when threats of arrest were directed at other prominent activists in the movement, including the seminar’s leader Mark Azbel.

Azbel was not arrested and received an exit visa in that difficult year. After his departure, Brailovskii took over the seminar, combining it with editing the journal Jews in the USSR. Three years later, in 1980, he was arrested.

Brailovskii recalls:[16]

There was a time that if a Western scientist came to Moscow and didn’t visit our seminar, upon his return home, he would encounter cries of dissatisfaction. … At our seminars I became acquainted with and heard lectures by six or seven Nobel laureates ─ an unbelievable number. Andrei Sakharov attended the seminar. … Ernst Neizvestnyi [the famous sculptor] gave a report and there were rabbis from the various denominations. … One seminar a month was devoted to cultural issues. … The regime was afraid of closing the seminar because it could have a serious effect on the country’s scientific and technological contacts. Thus, even after I had been arrested in 1980 and they set up a kind of KGB blockade around my apartment, they didn’t close the seminar. It continued to operate for some time, but then I was sent into exile … and my wife began to visit me … and the seminar had to leave our apartment. … The seminar made the rounds of various apartments; it was at Yakov Alpert’s for some time, at Alik Yoffe’s, and occasionally returned to our house. … When I returned from exile, the seminar continued to circulate and then in 1984-85 it revived. We occasionally held international sessions. About fifteen to twenty scientists arrived from various countries. There were reports, three to four days of sessions from morning to evening…. The American scientist Arno Penzias received the Nobel Prize for his discovery of cosmic microwave background radiation. He received it in 1978 and came to Moscow from Stockholm, visited our seminar, delivered a report that repeated his Nobel lecture, refused to visit the official Academy of Sciences institutions, and went home. … This was a very powerful act and it contributed to uniting the scientific world on behalf of aliya. … This segment of society had many opportunities to influence the higher ranks of the regime and this was an important part of the work….

Lerner’s Seminar

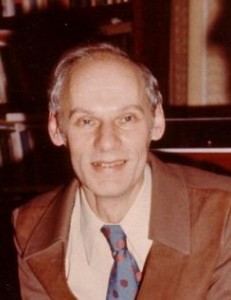

Aleksandr Yakovlevich Lerner (1913-2004), a very prominent scientist, quickly won recognition in aliya circles and deservedly belonged to the narrow group of leaders who took part in the most important decisions. In the summer of 1972, he established a refusenik seminar at his apartment on control systems and the application of mathematical methods to the solution of biological and medical problems. Dina Beilina was the secretary of the seminar until her departure. “The protocols of the sessions,” she recalls, “were sent to the Weizmann Institute, whose scientists took a lively interest in the seminar’s work. Lerner led the sessions very smoothly and there was an atmosphere of goodwill. People lingered after the seminar was over. Lerner’s wife, Judith, was a hospitable hostess and their home was open to everyone.”

The Weizmann Institute’s department of medical cybernetics took Lerner’s seminar under its wing. Eventually the seminar’s activities began to include reports and discussions on the problems of Jewish life in the Soviet Union and Jewish history and culture. Among the participants at various times were Eduard Trifonov, Anatolii Sharansky, Eitan Finkelshtein, Grigorii Freiman, Ilia Piatestkii-Shapiro, Viktor Brailovskii, Aleksandr Yoffe, Aleksandr Lunts, Yosif and Dina Beilin, Vladimir Slepak, Dmitrii Golenko, and many others. Important foreign scientists frequently were seminar guests. I also delivered a lecture related to my dissertation topic: “Some Telemetric Methods of Studying an Organism’s Functions.” Some scientists began to attend the sessions even before they formally applied for an exit visa.

Lerner, a broadly educated person with a shrewd grasp of the functioning of the state apparatus, quickly attained international recognition. Practically all the distinguished guests who visited the Soviet Union tried to meet him. Those meetings, to which he invited noted scientists and leaders of the Jewish movement, generally took place at his apartment. Lerner was an invariable and authoritative member of the movement’s political leadership although he never strove to be at its head. Even when he had to reduce his activity somewhat in 1977-78 because of the unprecedented KGB pressure, he always remained available for advice and discussion. I developed a fine personal relationship with him. During the difficult 1980s, when emigration practically ceased and there was a new wave of arrests, I often came to him for advice, always finding a wise analyst and a loyal friend.

Our good relations continued in Israel. When I came to interview him in February 2004, time had noticeably affected his external appearance but his mind retained complete clarity and his eyes sparkled with their former light. A month and a half later, this wise and courageous man with a kind Jewish heart was no longer alive.

Aleksandr Yakovlevich, where and in what kind of family did you grow up was my first question.[17]

I was born in September 1913. My father was a pharmacist; before the revolution he owned a pharmacy and under the Soviet regime he worked at his profession. In June 1941, he was mobilized into the army and perished at the front. His family came from the Pale of Settlement in the area of Vinnitsa. My mother, whose maiden name was Grinberg, was always a housewife.

Did your family observe Jewish traditions and holidays?

My grandfather and grandmother kept everything but my parents ─ not much.

That is, you were born into a fairly assimilated family and did not receive a Jewish education?

Yes, my parents didn’t give much thought to the matter. Nevertheless, when I was twelve years old, they found an instructor to teach me Hebrew and the prayers and they arranged a bar mitzvah according to all the rules. Thus, although they didn’t keep the tradition, they didn’t renounce it.

Where did you complete your basic education?

In Vinnitsa.

You were, no doubt, an excellent student?

Not at all; I was quite mediocre. I took an interest in science outside of the school program. I became acquainted with physics through Perelman’s book Entertaining Physics and with chemistry through the book Chemical Experiments, and I read a lot. I was not drawn to school studies as they were not taught well. I finished the seven-year school at the age of twelve instead of fourteen because I skipped a grade twice. I then graduated from an electro-mechanical technical school, and subsequently, at my mother’s insistence, I went to Moscow to study at an institute. I wanted to attend the Moscow Energetics Institute but I was not accepted because the acceptance committee ruled that my father belonged to the merchant class.

What year was that?

It was 1932. I then took courses at Energoprom [professional training offered by the state energy industry association] and from there entered the Energetics Institute. I graduated from it in three years and in another two years I defended my graduate dissertation ahead of schedule, which was unprecedented there. I was rewarded with a scientific work trip and other benefits; I was hired as an hourly worker at first and then accepted as a regular senior lecturer.

When did you defend your doctoral dissertation?

In 1943 I headed a scientific research laboratory on the automatizing of the metallurgical industry. The factory belonged to the metallurgy ministry. We were developing aggregate control systems. Two years later, I was invited to the Academy of Sciences, where my students were working, including Academician Petrov, the former director of the Automation Institute. He invited me to join the doctoral program and there I defended my doctoral dissertation, but that was already after Stalin’s death.

When did you begin to perceive the complexity of Jewish existence in that country?

Very early. I understood it and wasn’t the least surprised. The problems appeared, in particular, during the anti-cosmopolitan campaign in 1951. I was asked to leave the Automation Institute and with difficulty found a place in the Steel Institute. Subsequently I was also driven out of there, too, as a “cosmopolitan.” But Stalin died in 1953 and I was immediately restored to my position in the Steel Institute. Later I was asked to return to the Institute of Control Problems of the Academy of Sciences and I was given a laboratory there.

I know that before you applied for an exit visa, you directed a major scientific collective. What impelled you to take such a risky step?

It may surprise you but I had dreamed of this ever since my childhood, truthfully, as a pipe-dream. I used to participate in seder nights at my grandfather’s house and the phrase “Next year in Jerusalem” was engraved on my youthful heart. I dreamed of reaching Jerusalem sometime. When I understood that I could seriously consider the possibility, I began to seek a way of realizing it.

When did this happen?

Approximately in 1964, when people in the Baltics began to receive exit visas. I then decided that it wasn’t so fatal and I could try. If I had declared my desire to emigrate in Stalin’s time, I wouldn’t have lived long; I would simply have been shot.

You belong to a generation that lived through the Stalinist terror. Many Jews of that generation developed an insuperable fear of anything national.

Yes, but I wasn’t intimidated.

How did that happen?

Starting in 1960, I was permitted to travel abroad. My expertise was in a field that was very timely ─ the theory of optimal control. In essence, I was the initiator of this direction and received many invitations. I was allowed to accept one out of ten. I was in France, Italy, the U.S., Japan.… Abroad, I understood that freedom was worth any risks.

The KGB, no doubt, tried to recruit you for their tasks?

It tried, but I made it very clear that I wasn’t suited for that and they desisted.

You weren’t attracted to the dissident movement?

No. Soon after I applied for an exit visa, I met with Andrei Sakharov. We agreed to cooperate with regard to aid to prisoners and that our movement would deal only with issues of emigration and they would help us only in this matter.

When did you make the acquaintance of the leaders of the Jewish movement such as Polskii, Slepak, and Prestin?

In 1971, with my daughter’s help, I met Slepak, and he introduced me to the circle of activists.

Did you work with Vitalii Rubin’s humanities seminar?

No, but I worked with Rubin personally; he delivered lectures at my seminar.

In the first years the authorities did not interfere in the seminar’s activity. “We met in a calm atmosphere,” Lerner recalls.[18] “Our seminar discussed more than scientific problems. We also heard lectures on Jewish history and the State of Israel. For the time being, the authorities did not interfere with our seminar. We met in peace. We celebrated our one hundredth session, then the two hundredth. Practically all the Moscow refusenik scientists gathered at our anniversary sessions. There were refuseniks from other cities too.”

Aleksandr Yakovlevich, until what year was the seminar functioning?[19]

Until 1981. I’ll tell you how it ended. Three KGB officers arrived when the seminar was scheduled to start and declared, “That’s it. Your seminar is over.” One stood by the door to my apartment, two at the entry to the building, and they didn’t let anyone enter. They told everyone that the seminar was closed.

And then you had to close the seminar?

I wasn’t about to fight with them.

Vitalii Rubin’s Humanities Seminar

The third seminar, in the humanities, was organized in Moscow in the fall of 1972. The seminar’s first leader, Vitalii Rubin (1923-1981), mentioned that Voronel played a large role in its organization.

The initiative group numbered several friends ─ Mikhail Chlenov, Viktor Mandeltsveig, Dmitrii Segal, and Rubin himself. Some physicists, including Voronel, enjoyed attending this seminar. The reports touched on the fields of Jewish culture, language, history, tradition, and religion. There were, for example, interesting reports on Jewish mysticism (Segal), the history of Russian Jewry (Agurskii), about Hebrew (Dolgopolskii), and antisemitism, and book reports.

Heated disputes would arise, for example, between secular and religious participants, but generally they were quickly resolved and, on the whole, an atmosphere of good will prevailed. Refuseniks showed a great interest in the seminar; at times, fifty to seventy people piled into Rubin’s apartment.

Vitalii Rubin graduated from the Chinese Division of MGU (Moscow State University) in 1951. Entering the job market at the height of the anti-cosmopolitan campaign, he encountered the full measure of antisemitism, including problems in finding work. Even before that, he experienced many difficulties. His wife, Inna Akselrod-Rubina recounts:

He went to the front as a volunteer and wound up in captivity, where he spent all of four days; he escaped and returned to the army but was nevertheless placed in a Soviet camp for former military prisoners. In the camp he worked in a mine as a wagon hauler and developed tuberculosis of the spine, for which he underwent several operations.[20]

How old was he when you were married?

Thirty-two. He was five years older than me. It always seemed to me, however, that I didn’t deserve this happiness, which cast a shadow on it.

At first you were dissidents?

Unquestionably.

Did he know that you were the daughter of “an enemy of the people”?

Yes, of course, and it didn’t bother him in the least. People were being rehabilitated then, but I think that even earlier that wouldn’t have been a problem. His uncle served time, and he himself…..

What made you think about aliya?

It was, of course, Vitalii’s idea, as he mentioned in his diaries. He was working in a central library, reviewing literature in various languages. He knew three foreign languages in addition to Chinese. He used to deal with literature on contemporary China, which didn’t interest him, but he could appear for work only twice a week, although he had to cover a certain amount of material. He was interested in science but his attempts to transfer anywhere were fruitless. Strange as it seems, ultimately, he was accepted at the China Institute. He worked there for three years, wrote a dissertation on Confucius, and defended it. He then wrote a book, The Four Greatest Ancient Philosophers in China. The idea of leaving the country arose at the time of aliya from Soviet Georgia. We requested an invitation from Israel in 1971 but waited a long time without receiving it. The invitation was brought by Judy Silver, the American friend of Garik Shapiro at the end of December. In February 1972 we applied and in August we received the reply that my mother, who had died by that time, was granted an exit visa but we had been refused.

How often did Vitalii speak at the seminar?

Frequently. He gave an excellent report on the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig and later gave one on the Leningrad Hijacking Trial ─ that was already at Kandel’s apartment[21] ─ and several book reports.

When was the first session of the seminar?

In the fall of 1972, soon after we had received a refusal.

Were issues of emigration discussed at the seminar? I asked Feliks Kandel.[22]

Political topics and emigration issues arose in the course of many reports, especially after the lecture was finished and the question period began. Because the topic was so timely, many lectures naturally and unnoticeably drifted into those issues. This happened constantly. After the session some people would leave, while those remaining continued the discussion over tea, touching also on general topics.

Was the symposium on culture also discussed?

Discussion about a symposium began a half year before its start, in the summer of 1976. Generally, the discussion began after most people had gone home. Five to six people would remain; we wouldn’t talk but wrote to each other on the “magic slates”.

Rubin was, undoubtedly, a charismatic personality. He quickly became known in the West and many people fought actively for his freedom. His excellent linguistic ability enabled him to establish good relations with foreign correspondents, western activists and with people in the American embassy and to develop many friendships in those circles. After Vitalii’s departure in 1976, Arkadii Mai headed the seminar.

The Engineering Seminar

At the end of 1973, I moved to the apartment vacated after Nora Kornblum’s departure and acquired friends among my new neighbors. Soon I was receiving a stream of visitors who wished to consult about emigration issues, Israel, and refusenik life. One of my new acquaintances, a charming dissident, Igor Abramovich, introduced me to Lev Karp, who possessed an advanced degree in technical sciences and was interested in emigrating. He had been working until recently in some technical position in the CPSU Central Committee apparatus and was sure that he would have to wait several years before he could even apply for an exit visa. He was terribly afraid of disqualification on the grounds of secrecy considerations. I told him about the seminars.

Some time later he came to me again and stated that, unfortunately, the seminars were not in line with his interests, which were in the field of electronics. We agreed that it would be good to have our own seminar. Lev Karp and Igor Abramovich were immediately invited to deliver several lectures and I decided to check whether the idea was feasible. I talked with Slepak, Polskii, Prestin, Pasha Abramovich, Begun, and Volvovskii, who all had an interest in radio electronics, and they liked the idea. All of them, except for Polskii, expressed a desire to participate. I spoke with several more refuseniks and got together about ten people. Some of them, such as Igor Abramovich and Lenia Volvovskii, not only gave talks but also were part of the group of attendees.

The general mood was rather optimistic. At that time about 30,000 people were emigrating annually and we were sure that we, too, would succeed in getting out in a year of two. It was perfectly natural to wish to maintain our professional level before our departure. Aside from our professional interests in the seminar, as active members of the Jewish movement we found it useful to associate in a close circle and exchange opinions on the numerous pressing problems. I was responsible for arranging the seminar’s meeting place and other organizational matters. We used to meet once a week for about three hours, after which several people remained to discuss timely issues.

It was always interesting: our regular lecturers were Lev Karp (methods of optimizing control, planning computer complexes), the known dissident Yura Shikhanovich (methods of mathematical analysis and group theory), Lenia Volvovskii (synthesis and analysis of discrete automatic machines). Some seminar participants delivered individual reports and other refusenik scientists were invited as guest lecturers on special topics.

The engineering seminar operated for about two years. Under its influence, a similar seminar was set up in Leningrad that met in the apartment of Aba Taratuta. The signing of the Helsinki Accords engendered hope about new possibilities, and some of the seminar participants began planning an international symposium on culture.

The Helsinki Accords of 1975 indeed encouraged several new initiatives with regard to samizdat journals and scientific and legal seminars in various cities, which will be described later.

[1] Morozov, Documents on Soviet Jewish Emigration, p. 173 (see chapter 26, p. 000).

[2] Mark Azbel, Refusenik: Trapped in the Soviet Union (Boston, 1981), p. 283.

[3] Alexander Lerner, Change of Heart (Minneapolis, 1992), p. 192.

[4] Aleksandr Voronel, interview to the author, April 11, 2007.

[5] This is the title of Voronel’s autobiographical and philosophical work that was popular in the samizdat of the 1970s. It has been republished inIsrael in Russian.

[6] This was an organization of American scientists who supported the struggle of refusenik scientists in theSoviet Union. It was formed with the support of the Israel Liaison Bureau.

[7] Mark Azbel, interview to the author, March 26, 2006

[8] Dan Roginskii, interview to author, August 22, 2004.

[9] Mark Azbel, Refusenik: Trapped in the Soviet Union (Boston, 1981), p. 303.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., p. 305.

[12] Cited in the Jerusalem Post, June 18, 2003]

[13] Azbel, Refusenik, p. 306.

[14]Ibid., p. 332.

[15] Mark Azbel, interview to the author, March 26, 2006.

[16] Viktor Brailovskii, excerpts from interview to Aba Taratuta, on the site of the organization “Zapomnim i sokhranim” [Remember and Save], http://www.soviet-jews-exodus.com.

[17] Aleksandr Lerner, interview to the author, February 2004.

[18] Lerner, Change of Heart, p. 193.

[19] Lerner, interview to author.

[20] Inna Rubin, interview to the author, February 19, 2004.

[21] The seminar moved to Feliks Kandel’s apartment in 1974. It was preferable to hold the seminar in his larger, separate apartment in a writers’ building where the cultured neighbors were more tolerant of such gatherings.

[22] Feliks Kandel, interview to the author, April 25, 2006.