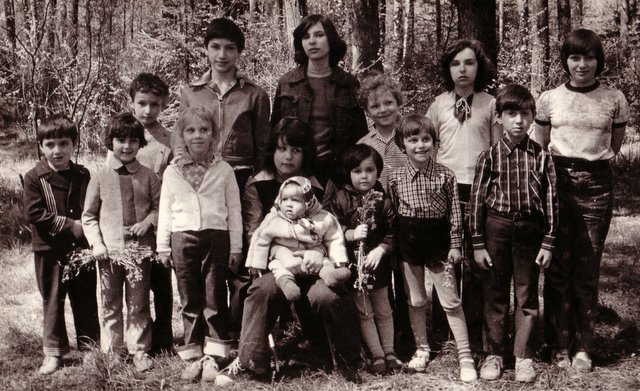

Children who were in refusal for a long time were a special, painful problem. Many parents decided to make aliya to Israel for the sake of their children and their future. But the years passed in refusal, the future remained unclear, and at that tender age the children were wedged between the same millstones of the state machine that crushed their parents’ lives.

The adults faced their ordeals with full awareness but the children became the victims of the arbitrary regime, often without comprehending what was occurring.

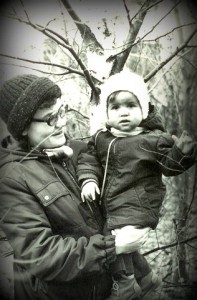

I’ll never forget a search in my home at the end of 1981. My youngest son was a few months old, the middle one three years, and the oldest thirteen. The search lasted from the morning until two o’clock at night. They rummaged through the children’s things, pulled the baby out of the carriage, and collected the children’s books and postcards with inscriptions in Hebrew, textbooks, and toys. At the end of the search, the senior KGB officer declared that they were also taking me away: “You can say good-bye, you won’t see him again,” he said to my wife, half-joking and half-serious.

Evidently he was “joking” because I was released the next morning. But my wife’s milk dried up and our youngest son Mattityahu grew up on an artificial substitute that was very hard to obtain in Soviet conditions.

In an analytic survey for Israel we wrote:

The children are much more defenseless than adults in the face of the ordeals, which begin at a preschool age.

It is impossible, of course, in official Soviet kindergartens and schools to raise children in the national traditions: Hebrew instruction, celebration of holidays, and the study of Jewish history. Many parents work hard to establish children’s groups and to organize holiday celebrations and various lessons. Even these elementary efforts are often subject to severe harassment. All these conflicts and visits by policemen and people in civvies that drive even adults crazy leave much deeper scars in a child’s psyche.

Israel receives more attention than any other country in all the television and radio broadcasts, in the press, including children’s newspapers and journals, and in lessons and political talks in school. It is instilled into the children that Israel is a synonym for inhumanity and cruelty and that Zionism is a form of fascism. But insofar as the children and their parents identify with Israel, this places them in tense, often hostile relations with their milieu. For some children, this leads to constant conflicts with their peers in the courtyard and in school and a strong desire not to attend school; other children suppress it, but, in any case, it creates unbearable tension and a state of constant discomfort and stress that accompanies their entire childhood.

Children’s relations with their peers are particularly problematic. Childhood friendship assumes a maximum degree of openness that is impossible in the specific case of refusenik children. Parents have to expend great efforts to convince their children not to tell outsiders about many—and the most important—facets of their private lives. Such concealment is a necessity in the refuseniks’ lives, but it leads to considerable alienation from one’s peers. This problem might not have been so acute if the refusenik children lived in a compact area and could be together, but, in fact, they live rather far apart. They couldn’t travel around town on their own and thus each had to solve a pile of problems alone.

As the children grow up, the problems become more complex. In particular, the issue of army recruitment becomes acute because after army service, a young person is not allowed to apply for an exit visa for many years. The social issue becomes sharper and, at times, tragic for the entire family when it comes to marriage: far from every potential spouse is willing to share the difficulties of refusenik life. The last but not the least significant is the problem of obtaining a higher education.[1]

The refuseniks tried as hard as they could under the circumstances to guard their children from at least part of the suffering. Although the regime used various pretexts to prohibit many initiatives, nevertheless, in the second half of the 1970s, first some refusenik kindergartens began to operate, and then Sunday schools and summer camps started. There was a shortage of experience, funds, and knowledge and of suitable premises but the passionate desire to afford the children the joy of playing and socializing with each other and to bring them closer to Jewish history, culture, and religion and to impart a feeling of natural pride in their nation won out.

The refuseniks and their friends abroad encouraged the children, especially the adolescents, to correspond, which, among other things, stimulated the study of foreign languages. Popular practices included the exchange of souvenirs, sending books and study material to the Soviet Union, and the simultaneous celebration of bar and bat mitzvahs.

As far as I know, the first kindergarten in Moscow was organized in 1977 by Galia and Zhenia Tsirlin.

Yes, affirms Natasha Khasin.[2] And when they saw that they lacked the money to rent a place, Zhenia Tsirlin, a very decisive individual, declared: “The kindergarten will operate at the Khasin’s apartment,” that is, in our house.

The kindergarten remained in our apartment for a few years. Subsequently the Tsirlins obtained an exit visa, and Ira and Boria Ginis took it under their wing. After they left, it was taken over by Katia and Liusik Yuzefovich, Zhanna and Evsei Litvak and the Lifshitzes. The kindergarten moved to the area of the Botanical Garden. Sema Azarkh joined them and helped them a lot. Then Yuri Shtern brought his girl there and also joined in. He was still part of the democratic movement but gradually, I think, partly under the influence of our kindergarten, he changed. In 1980 our Yudka became three years old and she also went there. We then rented a dacha in Kratovo, but a year later the KGB drove us out from there.

What were the children taught?

Volodia (Zeev) Kuravskii taught them Hebrew and the Bible. His children were also in the kindergarten. At first we wanted to invite someone from the synagogue to teach the Bible. When Galia Tsirlin went there to inquire, she was told: “Galochka, we could do it, but keep in mind that we will immediately be summoned to the KGB and forced to write a report”. Volodia Kuravskii then took it upon himself. They studied Torah, Hebrew, music, drawing, and mathematics.

Then others joined—Ira and Igor Gurevich, Rimma and Volodya Mushinsky, you, Masha and Victor Fulmakht. Masha Fulmakht taught drawing.

I remember that there were bunk beds there.

Yes, they appeared right away as otherwise there was a catastrophic shortage of space; then the beds were moved with the kindergarten from place to place.

Did you get a permit to open up a kindergarten?

No. Tsirlin read somewhere that a private kindergarten does not need a special permit. But the authorities went after us all the time and forced the apartment owners to drive us out. When we moved to Rimma Nudler’s—and it was harder to pressure her because it was her own apartment─they even tried to take the apartment away from her because it was used “not according to its designation.” They tried to intimidate her but in the end they gave her a visa and once again we needed to find a new place.

The Torah teacher Ilia Essas organized a religious kindergarten.

When did you do this, I asked him. [3]

In 1979. It started as lessons with children and then smoothly turned into a kindergarten.

Were the children brought there every day or did they spend the week there?

In 1981 at a dacha in Bykovo, we tried to have them sleep in during the week, but the police came and broke it up. Then I moved our summer studies to Yurmala. In order not to attract excessive attention, I made the following rule: I would not be in contact with Jewish circles in Riga even though my friends were there and I used to visit them at other times during the year, and they must not come to our camp. I calculated that the Latvian KGB wouldn’t take an interest in us as long as there was no evidence of any connection between the activity of our camp and local activists and, at the same time, the Moscow KGB would be preoccupied with Moscow matters and wouldn’t interfere in Latvia. That’s what happened. For four years, starting in 1982 and until my departure, the summer camp operated in Yurmala for 70 days each summer. During that time, we studied Torah and Jewish books. A stipulation was that parents also had to study. In the morning, I would take the children for exercise in the forest, followed by prayers, breakfast, and study. Then we took them to the beach. You had to see it: the old Jews wept when they saw the children in kippot.

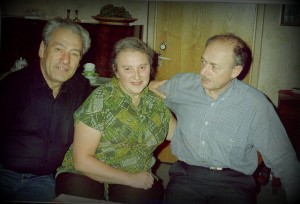

Slava and Mark Shifrin also organized a kindergarten and Sunday school for refusenik children.

We started the kindergarten in 1981, recalls Slava, and ran it for five years, until our departure. After we left, others took charge of it. In addition, we had the Sunday school from June 1, 1981. At first we rented a dacha for the school, but later it moved to our apartment. Lessons started from nine in the morning and continued practically all day. One group would follow another.[4]

How many groups studied in the school, Slava?

We had three different age groups. The first corresponded to elementary school, the middle to the sixth-seventh grade, and the oldest to the eighth and ninth grades. Over 150 children passed through the school.

We started it for the sake of our children. We have two. At first we tried to find some place for our older daughter—she was thirteen years old, but we didn’t find anything and decided to start our own.

Did you receive support from abroad?

Well, what do you think! You yourself sent people to us and helped.

Did you have independent channels?

Yes. In the Sunday school everyone worked for free, but in the kindergarten the teachers were paid. After all, the children arrived on Monday and left on Thursday evening.

Was anything else happening in addition to the kindergarten and school?

We held lessons for students of institutions of higher education.

Who taught them?

My daughter Emma taught the girls and Boria Shokhman the boys.

You mean that you ran a kindergarten, Sunday school, and lessons for students from 1981 until 1987?

Yes, six years. The KGB hunted us…you yourself know how it was. After we left, Esther Khutorianskaia assumed this burden.

Ira and Igor Gurevich had another Sunday school in their apartment in the very center of Moscow near the Park of Culture metro stop. “A durable brick building of Stalinist construction, an enormous living room, a large second room, a large kitchen, there’s a place to drop one’s coat when up to seventy people crowd in…. And an entire gymnastic complex in the second room, an excellent thing for our Sunday school,” wrote Elazar Yosefi (Liusik Yuzefovich) in his memoirs. “International meetings, Purimspiels, holidays, all at their place. The Gureviches gave a lot to the country…selflessly.” [5]

Ira, how did your famous Sunday school get its start?[6]

It began because our children grew up and went to school. We no longer could keep them together for a whole week as we did in the kindergarten. We then established a Sunday school.

When did it open?

Our Marik went to school in 1984, so that means it started then. We left the country in 1988, but the school continued to operate even after our departure.

Who taught there?

Volodia Meshkov (Judaism), Liusik Yuzefovich (history, Zionism), Masha Fulmakht (drawing), I, my husband Igor (math), and Alla Dubrovskaia (music).

How many hours of lessons were there each day? I asked Igor Gurevich.[7]

From nine o’clock in the morning until eight in the evening. We had an hour recess before lunchtime: first we took a walk, then we ate, and afterwards the lessons continued. The children were divided into four to five groups. They studied in every room. There were a lot of children: sometimes fifteen to twenty came.

Did you provide food for the children?

Yes, we kept completely kosher and prepared the meals ourselves.

What else of interest did you do?

We performed plays, “Purimspiels”…. The women wrote a booklet about our kindergarten called Children in Refusal.

Thus, three kindergartens and two Sunday schools functioned in refusenik Moscow and a religious summer camp operated in Yurmala.

As mentioned in the analytic report cited above, the problems became more complex as the children grew older. Attaining a higher education was particularly problematic because, in addition to the general discrimination against the entrance of Jews to institutions of higher education, the refusenik children were regarded as traitors taking the place of Soviet children. Entering such an institution, however, was the safest way of avoiding army service, which, among other things, carried the risk of losing any chance of obtaining an exit visa.

When the disqualification of Jewish applicants on entrance exams became especially blatant, some mathematicians decided to clarify how the anti-Jewish filter operated.

You applied to Moscow University and you were rejected on the basis of an exam? I asked Mikhail Bialyi, a doctor of mathematics and professor at Tel Aviv University, whose father and grandfather held degrees of doctors of science.

Yes, I applied in 1979 and received a mark of two [fail] in the written math exam. It was organized in the following way: Jews were sent to a special auditorium where they were given problems that were impossible to solve at the exam, so-called “coffins.” The system was functioning for many years.[8]

Who challenged the system?

A professional mathematician, candidate of sciences and dissident, Boria Senderov, undertook to help the Jewish children as part of the struggle against the regime. There were other mathematicians─Boris Kanevskii and Bella Muchnik (Subatovskaia) who helped. When a Jewish applicant received a “two,” they would advise him and help him to write an appeal quickly, because an appeal was legal only if it was written within an hour. They had been dealing with this for many years and everyone knew about it. There were even collections of “coffin” problems. A Frenchman named Vardi wrote an article on this topic. Professor Grigorii Freiman dealt with it quite actively.

How did they determine who were the Jewish applicants?

First of all, they knew many of them because Senderov and Kanevskii taught in the Second mathematical school. Someone else knew the others.

What happened to you?

I wrote an appeal and mama went to the chairman of the examination commission with a tape recorder and “guided” him to a frank answer.

Mikhail Bialyi’s mother, Judith Ratner, was the academic secretary of Aleksandr Lerner’s seminar from 1978 and later became a noted activist and leader of the women’s movement.

Misha, as far as I know, was in the group of the strongest pupils in the second mathematical school, I began my interview with Judith Ratner.

Yes, many talented Jewish boys studied there. He was failed on the written exam despite the fact that he solved all six problems─they simply wrote “failed.” All those who received a “two” wrote appeals but they were not accepted. When they understood that they would be blocked from taking the next exam, the fellows took away their documents in order to make it to the exams for other graduate schools. In the university the exams are given in July, but in other institutions of higher education, they are given a month later, in August. Senderov and Kanevskii, who fought against this shameful discrimination for many years, told the graduates of their mathematical school: “Even though you won’t succeed, you should try. You must show that you have not given up the fight.” The two men and Bella stood by the entrance and gathered data that would enable them to work out statistical information about acceptance. We organized a press conference right away.[9]

Misha said that there was another story with a tape recorder.

Yes, the dean of the faculty, a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences, Kostrikin, had office hours for the parents of applicants. After the boys were failed, I decided to go in order to gather material for the press conference.

Were there many people in the waiting room?

Yes, I waited my turn. Before entering, I turned on the tape recorder, which was in my pocketbook, and it buzzed. I could hear it and was terribly afraid they would discover it… after all, it’s somehow not nice to act secretly…. That was my morality then. But they didn’t discover it.

How did you manage to draw the dean into a frank discussion?

I said, “I am the mother of Misha Bialyi, who, having solved all six problems, received a ‘two.’ But I don’t even want to ask you about that. How do you explain the fact that the fellows who won international math Olympiads, gold medalists, very talented and capable, are not accepted to your faculty?” He calmly answered, “I won’t accept either Jews or Tatars. The previous dean Efimov accepted Jews but I won’t.” Not expecting such frankness, I became terribly angry and turned red. “Listen,” I said, “no decent person in the world would shake your hand. You are simply an antisemite.” And he said to me, “Get out of my office.” I left and was worried about only one thing: had these words been recorded?

You didn’t try to clarify the reason?

No, I didn’t try. I left, all crimson and upset. I checked whether his words had been recorded and calmed down. I sat in the reception room and came back to myself. A woman with some kind of sheet in her hands was sitting next to me. She said, “You know, my son, who is completely Russian, passed the written exam successfully, but he was flunked on the oral one because he looks so much like a Jew.” She was the mother of a boy with the last name Koshevoi, who also studied in Misha’s class. I asked her, “So what?” “I was advised,” she said, “to go to Kostrikin with the family genealogy.” I thought, “What luck!” “Permit me to wait for you,” I said. She went in and was also all red and agitated when she returned. “Well?” I asked. “You know, I showed them the documents. They said it doesn’t matter but added that perhaps my son has the knowledge after all; let him appeal.” Then I told her that I was the mother of Misha Bialyi. “Oh,” she said, “I heard how awful it was, that they failed the best boys.” “You know,” I said, “we decided to fight against this and we want to conduct a press conference. Could you give me this piece of paper without the indication of the family name? Just the fact itself.” She thought for a long time, “Your family won‘t be identified,” I convinced her. She couldn’t make up her mind, but then she waved her hand and said, “For the sake of the just cause, take it!”

The fact that Dean Kostrikin was an antisemite does not explain everything. After all, he held an official position, belonged to an institution, and it’s unlikely that he would have dared to act without approval or even direct orders from above.

I think that in justifying their position the authorities thought, “All those boys will then leave the country.” My close friend, the daughter of the mathematician, Academician Sobolev, quarreled with me after this campaign in the university. I asked her directly, “Zhenka, why do you think that I am wrong?” She said: ”Because your son plans to leave and he will take the place of a boy who will remain in the Soviet Union after he finishes his studies.” I uttered the banal phrase, “But, really, science has no borders!” She replied indignantly, “It certainly does!” It seems to me, that was the general opinion of the entire academic establishment.

They could talk that way about refusenik children but not about Jews in general.

Why not? They could. In their mind all Jews were potential emigrants.

Then how do you explain the similar attitude to the Tatars?

In that case, he simply let the cat out of the bag. Evidently, xenophobia was his outstanding characteristic.

A week later, we organized a press conference. I sought out people who could help since my English was still weak. Lerner refused.

He, of course, considered that one should apply one’s efforts to aliya and not to the domestic struggle.

I don’t know. He advised me not to do it or to go with the tape recorder… he was opposed and I was very close to him and usually listened to him. In addition, my parents said, “Do what Aleksandr Yakovlevich says; he is a wise person and has a lot of experience.” But, nevertheless, I said, “No.” Lev Ulanovskii agreed to help. His English was excellent and he knew foreign correspondents. Before the press conference, I went to the central acceptance commission, which included the deans of all the faculties and the rector, Logunov. I came with the tape recording to show them how antisemitism was flourishing in the mechanical mathematics faculty. They began to yell that it was slander, but they refused to listen to the cassette. They suggested that I leave it with them, but I immediately refused.

Before the conference itself, we also phoned the newspaper Pravda. Why? The previous day it carried a headline “Higher Education Competition” above an article that noted the objectivity of acceptance to the universities. It contended that the applicants’ names are coded so that you can’t bribe your way in. At Pravda’s editorial office, they said that they did not even know who wrote the article.

There were seven to eight foreign correspondents at the press conference. The participants on our side were Boris Senderov, Boris Kanevskii, and Volodia Cherkasskii from the refuseniks.

Were there any consequences or results?

Two. The positive one was that five boys, including my son Misha, were accepted into the university. And the second, negative, was that a couple of months later, they caused me to be in a car accident.

Why do you think that they “arranged it”?

At the time, we did not discuss that possibility. I was, you could say, on my death bed and not up to that…. I entertained the thought, but there was no proof. Many years later, already after our departure to Israel, THEY themselves admitted it.

In 1979, at the peak of aliya, after the terrible Sharansky trial…what’s the motive?

Apparently, they were sore losers, and we had clearly outplayed them, publicizing the matter. Kostrikin was dismissed from his position as dean. You don’t put someone in prison for a thing like that, but crippling her… That’s what we learned many years later. My close friend and her husband participated in our refusenik events and traveled to our celebrations. They were Jews but didn’t plan to leave the country. The KGB recruited her husband to tail us. He himself took it very hard. In the end his wife told us about it: “Marik is absolutely horrified that he can’t refuse… we simply can’t live.” We remained friends. I said, “Don’t torture yourself. Whatever they shouldn’t know, you, too, won’t know. And what they do know, they also can find out without you; we don’t conceal it ourselves.” Several years after our departure, Mark accidentally met our KGB “curator,” Yakimenko, who asked him, “Well, how is Yudif Evseevna doing there in Israel?” “Normally, my wife corresponds with her. Do you want the address?” “Well, no,” said Yakimenko, “it’s not hard to find the address. But look, we crippled her.” That was in 1990. Mark was simply taken aback. For the first time, I received some confirmation of the conjectures that had arisen then. My friend described this incident in her memoirs.

You don’t think that they simply wanted to intimidate poor Mark?

What for? It was 1990, deep into perestroika, free emigration…. Sakharov also wrote about those methods and cited names.

Naum Meiman’s refusenik mathematical seminar played no small role in exposing the mechanics of failing Jewish applicants to the mechanical mathematics faculty. Serious mathematicians, doctors of science took part in it. Academician Sakharov also attended this seminar.

What did you manage to discover? I asked a participant of the seminar, Gennadi Khasin.

Sakharov and Meiman wrote an article on this topic and published it in a French journal. How did the system work? Jewish applicants were put on a separate list, which was given to the examiners who were supposed to fail them. The Jewish fellows were summoned to them to take the oral exam. If the applicant failed to solve two of the problems given him, that was proper grounds for failing him. The examiner would continue posing problems until two were not solved and then he would place a “failure” mark. They were breaking the law in any case because it is not permitted to examine an applicant for more than two hours. Two of my pupils underwent that kind of exam. One of them was subjected to seven hours of questions.

We conducted an experiment at the seminar. The participants were given five problems from those that the Jewish applicants had received on entrance exams. Boris Senderov brought them. It was suggested that we cut short our working time because the students were given twenty minutes per problem. Only two of us solved all five─Alik Yoffe and I. It took Alik, however, three hours and twenty minutes and me─four hours and forty minutes, that is, we also couldn’t manage in the allotted time. Sakharov was very pleased that he solved two problems and proudly bought them to Meiman. The problems were absolutely, brainbusters. An article was written about the topics of these problems.

Senderov, Kanevskii, and Subatovskaia played key roles in exposing and publicizing the examination obstacles and traps. All three were professional mathematicians who prepared pupils for applying to mechanical mathematics faculties and personally were upset by their rejections. For those who had failed the exams and wanted to continue studying, they organized a “People’s University” in 1978 that operated on a voluntary basis. All three suffered in 1982, when the clouds again gathered over activists in the dissident and Zionist movements. Senderov was sentenced to seven years of a strict regime labor camp and five years of exile, Kanevskii to five years of exile, and Subatovskaia was run over by a truck on a dark Moscow street. None of those close to her had any doubts whether it was murder.

Kanevskii now lives in Israel, where he teaches math in school and the university. Senderov returned to Moscow after serving his term and remains the same stubborn fighter against injustice.

What led you to the issue of entrance exams? I asked Boris Kanevskii.[10]

In my spare time I taught a special course in the Second mathematical school. When one after another of our pupils failed the exams, we began to look for the reasons. That was in 1974-75….

Did you think it was on orders from above?

A political decision, of course, exacerbated by personal zeal.

They say that the situation wasn’t so outrageous among physicists.

That’s not so. At the Moscow Mathematics Olympiad (there wasn’t an all-Union one then), I received third prize. After the third round, all the winners were invited to the physics faculty. The first two agreed to go, but they were disqualified by the medical commission─that is, Jews were rejected not only at entrance exams. In the physics faculty Jews were rejected in various ways. Sometimes, however, they were quietly accepted. I know of two or three strong students who studied in our People’s University and in parallel studied in the physics faculty, i.e., they had been accepted.

How many people usually studied in your university?

It depends on the year. In 1978 nineteen started. By the end of the year, of course, there were fewer. The following year and onward it reached over one hundred. There were general lectures for everyone but the second day of studies was in seminars for smaller groups.

Were you also involved in articles about the disqualifying at entrance exams?

Yes. First, it was an article about thirteen problems and their level of difficulty based on the results of 1978, signed by a large number of participants of Meiman’s seminar. Grigorii Freiman’s book that he wrote in 1976, It Seems That I am a Jew was published in 1979 in the journal Jews in the USSR. In 1979, statistics appeared concerning the results of evaluations in six of the best Moscow schools.[11]

There were many unemployed doctors of science in refusal. They willingly studied with small groups of applicants or pupils. In this sense, some Jewish students had very high level advisers and, despite the discrimination and complexity of life in refusal, they were more successful in advancing in their studies than their peers.

[1] Analytic report prepared byMoscow activists for the Liaison Bureau in 1984.

[2] Natalia Khasina, interview to the author, April 29, 2006.

[3] Ilia Essas, interview to the author, May 6, 2006.

[4] Slava Shifrin, interview to the author, May 5, 2006.

[5] El’azar Yosefi, Dorogoi dlinnoiu (Jerusalem, 2005), pp. 290-91.

[6] Ira Gurevich, interview to the author, May 5, 2006.

[7] Igor Gurevich, interview to the author, May 5, 2006.

[8] Mikhail Bialyi, interview to the author, April 27, 2007.

[9] Judith Ratner, interview to the author, April 29, 2007.

[10] Boris Kanevskii, interview to the author, April 27, 2007.

[11] A series of articles appeared on this topic: B. Kanevsky, N. Meiman, V. Senderov, and G. Freiman, “Results of the Admission of Graduates of Five Moscow Schools in the Department of Mechanics and Mathematics of Moscow University in1981,” Open Society Archives at Central European University, AC No 4696.