Samizdat (independently prepared and distributed, uncensored printed material, Yu. K.) seems to exist in every totalitarian society. Its function is to sate the intellectual and informational hunger created by the official censorship. Among the refuseniks its function was much broader, encompassing education (books on Jewish history, religion, and culture and textbooks); information (newspapers, journals, information bulletins, and chronicles of the struggle); an instrument of the struggle (letters and appeals to Soviet and foreign bodies); and a format for the self-expression of people under the constant pressure of the punitive organs. Samizdat was our means of communicating with the Jewish world and the West, facilitating mutual understanding.

Toward the end of the 1960s, it had already become clear that publications in the West were a most important component of our struggle. Many appeals, letters, and declarations were therefore addressed not so much to Soviet state organs as to international Jewry or Western society.

The Jewish national movement, including the Jewish samizdat, did not aim at reforming the Soviet social or political order. The content of our samizdat reflected the emigration struggle and the national revival, and its editors and authors tried to keep their published material within that framework. Neither of these themes was in conflict with the Soviet constitution; therefore, as the rules of the game became more or less defined around the beginning of 1972, the Jewish samizdat began to acquire a practically open character.

The cover of the first issue of the journal Evrei v SSSR [henceforth referred to by the English translation─Jews in the USSR] carried the names and addresses of its editors─Aleksandr Voronel and Viktor Yakhot. The majority of authors signed their works because, along with the danger of repressions, such openness and the associated recognition that accrued to its author afforded him/her greater chances of receiving an exit visa.

The samizdat press published little-known literary works on Jewish themes by well-known figures such as the verse of Vladislav Khodasevich, Mikhail Svetlov, Eduard Bargritskii, Ilia Erenblurg, Boris Slutksii, Naum Korzhavin, Alekskandr Galich, and Yosif Brodskii. New works by Nina Voronel, Aleksandr Radkovskii, Yurii Kolker, Igor Guberman, Boris Kamianov, Ilia Voitovetskii, Iulia Shmukler, Feliks Kandel, Ilia Gabai, Boris Khazanov, Mikhail Domalskii (Baitalskii), Ilia Rubin, Aleksandr Voronel and many others also first saw the light there. Historical research by Melamedov, Rivosh, Wagner, Romanovskii, and Praisman was also published in samizdat.[1]

Original and translated religious literature was actively disseminated in samizdat: for example, Habad by Grigorii Rozenshtein, I Believe by Mikhail Shneider, and Commentaries on the Bible by Ilia Essas. Textbooks for the study of Hebrew written by the refuseniks Ida and Aba Taratuta, a Hebrew grammar by Leonid Zeliger, and others were widely distributed in samizdat.

As contacts with the West expanded, refuseniks more and more resorted to “tamizdat,” [literally published there] that is, works published abroad.

Because the growing demand for books with cultural, historical, and religious content couldn’t be met by books from the West, some of those books were translated and reproduced in the Soviet Union, thus also turning into samizdat. Popular works in this genre included Leon Uris’ Exodus, Cecil Roth’s, A Short History of the Jewish People, excerpts from Dubnov’s History, and articles by Jabotinsky, Trumpeldor, and others. After access was arranged for supplying to the USSR books from the Russian-language “Biblioteka Aliya” series of books produced in Israel, many of them were also reproduced and distributed in samizdat. Other popular items in refusenik circles were cassettes with recorded songs in Hebrew and audio material for studying Hebrew.

All samizdat has three components: composing or compiling; preparing the copies; and distributing them. The punitive organs frequently harassed people involved in any of those stages. Even if it consisted of simple grammatical exercises in Hebrew, samizdat was always confiscated during searches and was an invariable factor at interrogations: “Who gave it to you?” “Who took it?” “Who dealt with the preparation?”

In and of itself, samizdat did not violate basic Soviet law if it didn’t contain a patent lie against the Soviet public and state order. In practice, however, the “organs” would treat as such any truth about the Soviet order that was undesirable from the Soviet leadership’s viewpoint. If this truth was disseminated too widely or made its way abroad, it could be classified as “slander directed at subverting the Soviet social and state order,” which was punished more severely─up to seven years of penal labor and five years of exile (the sentence for mere “slander” was three years of labor camp”).

The unsanctioned use of copying technology as, for example, Xerox machines, was a separate crime. The authorities would immediately open an investigation whenever uncensored material prepared by xeroxing, or worse, printing fell into their hands. The violators would be found and severely punished. At one time, even personal printing machines had to be registered and accounted for. Therefore, until almost the end of the 1980s, the most widespread methods for preparing samizdat were photographing and using typewriters with carbon copies.

“The earliest known Jewish samizdat dates from the postwar years; however, one can hardly speak of samizdat as a phenomenon of the Stalinist years. Individual examples were exceptions…. Only after Stalin’s death, the Zionists of the old prewar generation who were released from imprisonment initiated the new Jewish samizdat.”[2]

For many years, the samizdat promoted the revival of feelings of Jewish national consciousness and dignity. Among the many people who were active in this area in the 1950s and 1960 were Meir Gelfond, first in Zhmerinka in the group Eynikeyt (Yiddish for unity) and then in Moscow; Leah and Boris Slovin and Eli Valk in Riga; and Ezra Morgulis, Solomon Dolnik, Mairim Bergman, Vitalii Svechinskii, Izrail Mints, and Feliks Dektor in Moscow. Although the majority of works that appeared in samizdat were translations, there were also independent works. Thus “from 1962-64 Ezra Morgulis wrote a 600-page, two-volume work, A Survey of Jewish Communities (Obzor zhizni evreiskikh obshchin) that briefly surveyed the life of Jewish communities in the diaspora, told about their culture and links with Israel, and described in detail the situation of Soviet Jews, doomed to complete assimilation because of the regime’s antisemitic policy. Earlier, in 1960, Morgulis completed a monograph of about 230 pages, The State of Israel…. Tall, with a shock of gray hair, a good listener, he became the inspirer and organizer of the first Moscow circle of Jewish youth and intelligentsia.”[3]

“I recall my last visit to the ill Morgulis,” recalls Mikhail Margulis (not a relative):

Foreseeing his imminent demise, he requested that I continue his life’s work and he bequeathed me his archive. After his death (1965), a woman who was a member of his circle phoned and asked me to come to a dacha near Moscow. There she gave me an old suitcase that contained a large, typewritten book in a black binding, The State of Israel; the Israeli journals Shalom and Ariel in Russian; Vestnik; and a selection of material “Gorky on Antisemitism,” compiled by Ezra Morgulis and Solomon Dolnik. This material formed the basis for an illegal archive of Moscow Jewish samizdat that I supplemented until the fall of 1971, when Nera [his wife] and I left for Israel.[4]

In 1968 the manuscript of Yakov Edelman’s Dialogues was first disseminated.

A distinctive feature of the early samizdat was the absence of periodicals, which appeared only at the stage of an open struggle for aliya in 1969-70. At that time, the democratic dissident movement already had its publications Sintaksis (1960), Feniks (1961), and the Chronicle of Current Events[5] (April 1968). “The appearance of the Jewish periodical samizdat was a direct consequence of the emergence of a consolidated Zionist movement for immigration to Israel.”[6] The decision to publish the first periodical Iton (Hebrew for newspaper) was taken by the All-Union Coordinating Committee. The editorial board, which included representatives from Moscow, Leningrad, and Riga, succeeded in producing the collections Iton Alef and Iton Bet in 1970. Lev Korenblit (Leningrad) was the editor of Iton; Yosif Mendelevich (Riga) was the author of several articles and organized the copying and dissemination. Victor Boguslavskii (Leningrad) and Karl Malkin (Moscow) played active roles in the preparation of the collections. The third issue of the journal was confiscated and the editor, publishers, and distributors were arrested and convicted (some of them were tried in the Leningrad Trial).

A few weeks after the appearance of Iton, the journal Iskhod (Exodus) was published in Moscow.

Did the All-Union Coordinating Committee make the decision about both journals or was Iskhod a private initiative? I asked Vitalii Svechinskii.[7]

When Meir Gelfond and I split up into two activist groups, “alef” (the open one) and “bet” (the closed), those of us in “alef” decided that we could also permit ourselves our own Chronicle of Current Events. Iskhod became the Jewish Chronicle. The Committee had nothing to do with it; it was our initiative.

Did you indicate the editor’s name on the cover?

We, like the Chronicle, did not indicate the editors and compilers. The only one who did this at the time was Chalidze, and he included his telephone number and address…. Moreover, none of our people knew that the editor of Iskhod was Viktor Fedoseev, that his wife Alia helped him, and that her mother Dora Koliadnitskaia produced the edition. Yasha Ronenson─today he is Ronen─was responsible for storing and distributing the material, which I supplied.

The Democrats’ Chronicle began in April 1968. What about Iskhod?

In I970, the KGB was trailing us and was close on our heels. They managed to discover the edition that had been prepared before our departure. Ronenson hid it in a stove pipe near the Aeroport metro stop. Already in Vienna at that time, I was terribly fearful for the Fedoseevs and Ronenson, but they weren’t caught. The KGB found copies but couldn’t determine the source. After our departure, Iskhod fell into the hands of Isai Averbukh, and he put out the last issues.

But he’s from Odessa!

He’s from Odessa but he was spending his time primarily in Riga and Moscow. He is like quicksilver, solidly put together, unusual, with esoteric qualities, a poet and an expert on the soul. We love him.

Did the formation of a refusenik community begin with your journals?

It began with Voronel, not with us. His Jews in the USSR was the classic journal of community and resistance.

Iskhod consisted basically of letters and appeals by Zionist activists and material from trials. Four issues of 30-40 pages each were published from the spring of 1970 until the beginning of 1971.

After the arrest and conviction of the Riga-Leningrad group, the center of samizdat preparation and dissemination moved to Moscow. The journal Vestnik Iskhoda (Herald of the exodus) appeared in the capital in 1971-72. Vadim Meniker, Yuri Breitbart, Boris Orlov, and Mikhail Zand were active in its publication. Three volumes, each about 50-100 pages, appeared. In 1972-73 Roman Rutman edited three collections under the title Belaia kniga iskhoda (White book of the exodus).

At first, the Jewish samizdat reflected the influence of the democratic samizdat on the more assimilated Moscow Jewish intelligentsia. Considerably less influence was exerted on the Riga Jewish samizdat as the manifestation of old Zionist traditions was stronger there. In time, the journalistic samizdat freed itself from external influences and began to develop independently.[8]

The longest lasting and most influential Jewish samizdat publication, the literary-publicistic journal Jews in the USSR, first appeared in October 1972. In accordance with its subtitle: “a collection of material on history, culture, and the problems of Jews in the USSR,” the journal published material on emigration and assimilation; Jewish culture, history, and religion; and short stories and poetry.

The editors wrote in the introduction to the first issue: “We decided to begin a systematic study of the problem, using the criteria of scientific honesty to which we have become accustomed in our professional activity.”[9]

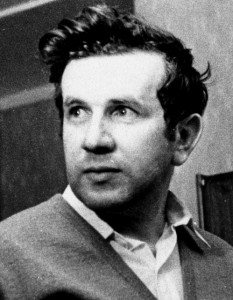

The authors of the articles in the journal were expected to be competent in the topics they undertook to write about and the material was not to be political in nature or contain slanderous information. The noted activists Aleksandr Voronel and Viktor Yakhot were founders of the journal.

When did the idea for the journal arise and what did it consist of? I asked Voronel.[10]

It arose in a conversation with Yakhot in 1971.

I thought that Jews should express themselves in their own words. Thanks to Nelli [his wife, a writer], I often associated with writers, and almost all of them were Jews. I was astonished at the degree to which none of them felt free to express himself as a Jew. There were tragicomic meetings in this sense, for example, with Aleksandr Moiseevich Volodin, a very successful playwright in Russia. We were close acquaintances and I would often visit him when we were in Leningrad. When I was already in refusal, I once dropped in with my samizdat and gave him something to read. He grabbed it, avidly read it, and said,: “This was so pleasant! For the first time I read the printed word ‘Jew’ without a blush of shame. Indeed, every time that I pronounced this word, I would look around and somehow feel awkward.” His real name was Lifshits, and, as a Russian writer, he not only was simply afraid but was somewhat ashamed of being a Jew.

Were you pressured because of the journal?

I was often dragged to the KGB, especially before the international seminar in 1974, when it happened almost daily. They tried to intimidate me on account of both the seminar and samizdat. The KGB officer would say about the journal, for example: “Of course this is not Article 70 but it approaches190.”I would reply: “No, because Article 190 is about slander, that is, a patent untruth. But I think that everything that we publish is the truth.” He: “That’s what you think, but I am telling you that it’s slander!” “And who are you?” I ask. “Who can determine what is truth and what is falsehood?” He says: “What do you mean? The KGB is telling you that it’s untrue!” I say: “That’s the first time that I hear such a definition of truth. After all, I am a scientist…” And I saw by his reaction… not that he agreed with me, but he said: “Keep in mind, if you persist, sooner or later it will end in [Article]190.”

Active participants in the journal’s work at various times included Moshe Gitterman, Mark Azbel, Boris Orlov, Viktor Brailovskii, Aleksandr Lunts, Bella Palatnik, Mikhail Agurskii, Ilia Rubin, Eitan Finkelshtein, Feliks Dektor, Rafael Nudelman, Emma Sotnikova, Vladimir Lazaris, and others.

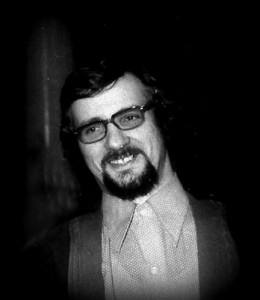

The last editor of the journal was Viktor Brailovskii. The human rights situation in the USSR deteriorated sharply after the Soviet invasion into Afghanistan in 1979. The winds of the Cold War were blowing again and the rules of the game changed. What had been acceptable during the détente period became cause for a bill of indictment under the new conditions.

Viktor, what was the concept of the journal in your day? I asked Brailovskii.[11]

It was very simple: to acquaint people with the foundations of Jewish philosophy, with the viewpoints of noted Jews in Russia, and with what others think about us. We translated a lot of material. There were rather interesting interviews with Father Men and with Andrei Sakharov. We also published belles lettres, philosophy, and even religious literature.

The authors were in the open but the printing and dissemination were concealed….

Far from all of the authors were open; many published under pseudonyms.

Were you dragged in [to the KGB] because of journalistic matters?

All the time. In the end, I was separated from the common case and charged specifically.

Who else was dragged in besides you?

I think it was [Ilia] Rubin, Sotnikova, Azbel, and Lazaris.

It was a case about slander?

Yes, Article 190-1.

After you were taken, the journal stopped coming out?

Yes, and it didn’t get started up again. In August 1979, the last issue, no. 21, came out.

It was a marvelous journal….

In retrospect, it should be noted that the flowering of samizdat journals was stimulated by the Helsinki Accords, especially the human rights “basket” that was so important for the Zionist and dissident movements. For the first time, human rights became an inalienable part of broader agreements on the recognition of postwar borders, strategic arms limitations, and economic cooperation.

In April 1975, before the signing of the Helsinki Accords, the journal Tarbut (Hebrew for culture) began to appear in Moscow. Dedicated to the history, religion, and culture of the Jewish people, it was initially published as a supplement to Jews in the USSR and even had a corresponding subtitle. One of the considerations in support of this format─the desire not to antagonize the authorities excessively with the appearance of yet another journal─disappeared with the signing of the Accords, and in 1976 Tarbut began an independent life.

Tarbut was the first journal after Jews in the USSR that reflected the developing cultural trend in the Jewish movement. It was followed by several others: Nash Ivrit (Our Hebrew), Evrei v sovremennom mire (Jews in the contemporary world), Magid, Haim, LEA (Leningrad Jewish Almanac), Evreiskaia mysl (Jewish thought).[12]

The “kulturniks” (supporters of the cultural trend) were seeking a way of reaching the Jewish masses while avoiding the most acute politicized topics that might intimidate the reader. The appeal that appeared in the eighth volume of Tarbut can be taken as the slogan of all the cultural journals: “Reader, don’t be afraid! This is your Jewish journal, your culture; there is nothing forbidden in it. Don’t hide the journal in the desk, under the pillow, or in the cupboard. Read it freely; read it openly. A people’s culture cannot be an underground one!”

Vladimir Prestin was a founder of the journal. He recalls that the first editors, Dr. Veniamin Fain and the writer Feliks Dektor, had already been involved in samizdat in the 1960s.

Why was Jews in the USSR insufficient? I asked Vladimir Prestin. Did you consider that Jewish culture should serve aliya?

I never said such a thing. We considered that even if we did not stimulate people to emigrate, but only imparted some knowledge to them, that also would be a good thing. In short, the cultural movement was something broader than emigration. We wanted to produce Tarbut for those two million Jews who were not yet ready. What distinguished that journal? It was “kosher”; the word “Zionism” didn’t appear there. We had an entire press and we printed it in large quantities. You surely understand that our hundreds of copies and… two million Jews! An illusion, of course.

In 1978, the journal Our Hebrew began to appear. Initiated by Pavel Abramovich, four issues were published. The first, entitled simply Ivrit and dedicated to the one hundredth anniversary of the rebirth of the language, appeared in October 1978 and the final one in December 1980. The journal contained articles on the history of the language and linguistics, interviews, works of Israeli authors, and much else. Abramovich was the editor and compiler of the first issue. Dina Zisserman worked with him starting from the second issue. “There were good sections,” recalls Dina Zisserman. “We chose from what we had, evaluated who could write what, and convinced people─you, for example.”[13]

In looking over the yellowing pages of the journal, indeed, I came across my own article about Hebrew teaching methods. It was published in the final, fourth issue and was preserved thanks only to the journal─my copy of the article was confiscated during a search. It was interesting to familiarize myself with my own thoughts from thirty years earlier. We shall yet talk about that.

What place did Our Hebrew occupy among the other journals? I asked Pavel Abramovich.[14]

After Ilia Essas became editor-in-chief of Tarbut, it acquired a more pronounced religious tone. Our Hebrew told about the miracle of the revival of Hebrew, its contemporary state, about the language as the core of the national culture, and methods of mastering it. We printed translations of poetry and prose by Israeli writers.

Was it a “thick” journal?

It was thinner than Jews in the USSR and approximately the same size as Tarbut.

Was there an editorial board?

At first, just me, but I lacked literary skill and I invited Dina Zisserman. We worked on the second issue together. Later Vitia Fulmakht joined us. The professional journalist Zhenia Barras actively participated in the work.

How large was the edition?

In Moscow we made around 100-150 copies. The journal was disseminated via the refusenik community. We would also give it to arrivals from other cities.

Did you stop publication because of pressure?

Not really. The journal simply exhausted its possibilities. I was the primary source for items. At some point I felt that there wasn’t any more worthwhile material. Just at that time, the journal Jews in the USSR was closed and I wanted to create a thick journal that would follow in its footsteps. We gave it the Hebrew name Magid (herald). After we put out one issue, they started to drag us into the KGB. One of their demands was that I stop working on publications─they mentioned Nash ivrit and Magid.

Were your pressured only because of the journals?

Not only. As you recall, the KGB presented me with a paper that they demanded I sign. It called on me to halt the independent publication of printed material, Hebrew instruction, and so forth.

I never signed anything at the KGB

Neither did I.

The final years of the 1970s détente, from 1978-79, were most productive in terms of the quantity of Jewish samizdat journals. In addition to the above-mentioned ones, in Moscow, the collection Jews in the Contemporary World (Evrei v sovremennom mire) (a chronology and translations of foreign authors) began to appear, edited at different times by Emannuil Litvinov and Viktor Fulmakht. Six issues were published from 1978 to 1981. The documentary collection Departure to Israel: law and practice (Vyezd v Izrail: pravo i praktika) was first published in February 1979. Members of the editorial board included Maia Riabkina, Ilia Tsitovskii, and Mikhail Berenfeld. Eight issues were published in the course of a year. In 1978 the collection Jewish Thought (Evreiskaia mysl), devoted to religion, culture, and philosophy, was issued in Riga and in 1979 the literary-publicistic journal Haim (Hebrew for life) began publication and continued until 1986. In the same year an informational non-periodical collection Din umetsiut (Hebrew: law and reality) appeared, existing until 1980. Yakov Aryev, Alekskandr Mariasin, Grigorii Shadur, and Valerii Sulimov were on its editorial board.

On December 25, 1979, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led to another round in the Cold War between East and West. The changed situation immediately affected the functioning of the refusenik community. The regime persecuted all forms of organized activity, especially the publication of periodicals. Nevertheless, new journals continued to appear in Moscow in the first half of the 1980s. Yosif Begun published a volume entitled Our Heritage (Nashe nasledie) in 1981 but on November 6, 1981, he was arrested (for the third time) and sentenced to seven years of imprisonment and five years of exile, the maximum punishment under Article 70. In 1982-85, Aleksandr Razsgon published twelve issues of the journal Digest, which included selections from the Soviet press on Jewish topics.

Although the Leningrad activists were able to participate in the publishing of the first periodical, Iton, the development of periodical samizdat followed a more difficult path there: after the hijacking attempts (the First and Second Leningrad Trial), the authorities cracked down on the activists very harshly. As a result, Leningrad dropped out of periodical samizdat production for a long twelve years.

In 1982, when the regime had almost crushed the Jewish samizdat in Moscow, the Leningrad Jewish Almanac (Leningradskii evreiskii almanakh, or LEA) began to appear. It published literary works and articles on literary criticism, religion, and history. Among the active participants were Eduard Erlikh, Grigiorii Vasserman, Semyen Frumkin, and Mikhail Beizer.

Matvei Chlenov notes the unusual fate of LEA, one of the most successful samizdat publications:

LEA appeared at the darkest period of the harassment of samizdat and continued to come out for the entire period of the 1980s. During this time, the journal’s level, both in terms of publicistic and literary works, remained very high, on a par with the best samizdat works of the 1970s. The end of the LEA is also symbolic: Semen Frumkin, the last LEA editor, transferred the material for the twentieth issue to the editorial portfolio of the Riga journal VEK. Thus, the Jewish periodical samizdat, which first appeared in Riga in February 1970, followed a circular path for almost twelve years, and merged with the newly revived legal periodical Jewish press.[15]

Who initiated the almanac, I asked Beizer.[16]

Yakov Gorodetskii and, apparently, Vasserman and Erlikh…. It was a tough time. Everything in Moscow had been crushed; the journal Jews in the USSR had come to an end. It was understood that people would now be arrested because of samizdat. In this sense, LEA had a particular significance, having transferred the center of samizdat periodicals to Leningrad. LEA existed for a long time: nineteen issues were published. It existed until it basically became legal. The [Hebrew University published] samizdat collections included only eight issues of LEA because, at that time, Professor [Mordechai] Altshuler had already halted the publication of samizdat collections.

At first I participated in LEA as an author. After Gorodetskii, Erlikh, and [Yuri] Kolker had left, the sole remaining editor, Frumkin, came to me. Moscow had already gone underground at that time. In view of the changed situation, we also went underground, forgoing the publication of names and telephone numbers on the first page. All those dissident things were discarded. The editing, copying, and dissemination were divided up. The editorial board prepared one copy and handed it over and that was it. There was never a copy in my house. Even my closest friends didn’t know who was editing the journal. When I was summoned to the KGB and asked all kinds of questions, they had nothing to say about the journal. Evidently, they suspected that I knew something because I had published excursions [of Jewish Leningrad] and other things in it under my name. But they didn’t know about the editing.

Did the editorial board receive financial help?

No. We did the creative part for our own pleasure and at our own risk. But we weren’t the ones who dealt with the production part, the payment to typists, or distribution.

Who dealt with the production process?

At first, Yasha Gorodetskii dealt with the financing. After he left, there was a generational change and we started to discuss how to keep things going. Frumkin and I asked Aba Taratuta to finance the journal without changing the name or form. We wanted to show the KGB that publication of the journal was not affected by either their arresting or releasing anyone. Anyone other than Taratuta probably would have said that he would finance it under the condition that it would be a different entity because he wouldn’t support someone else’s undertaking. For example, when I raised the issue in Moscow, I was told: “It’s your affair, after all, take care of it.”

LEA circulated well in other cities, too. It was a thick journal of about 70-80 pages with an enormous circulation for that time: we made at least 70 copies and in good times more than a hundred. In our day dissident journals made only one mock-up, for example Haim in Riga. It was truly a difficult time; many were arrested─Edelstein, Kholmianskii, and Volvovskii [in Moscow] and among us─Lein and Fradkova. Aba─you have to give him credit─agreed to remain in the background and support the journal because he considered that it was a necessary enterprise. Then guests and foreigners appeared. Leonid Kelbert had good contacts with the American Union of Councils for Soviet Jews. We were a cheerful group and had a good time together. At first, many wanted to go to America, but, as a result of this activity, they changed their orientation and wound up here in Israel.

The regime began to ease up a bit at the start of perestroika. Three issues of the Jewish Annual (Evreiskii ezhegodnik) appeared in Moscow from 1986-88. Vladimir Mushinskii, Grigorii Levitskii, and Zeev Geizel formed the editorial board. From 1987 to 1989, three issues of the Jewish Historical Almanac (Evreiskii istoricheskii almanakh) were published by the Jewish Historical Society, which was founded by Valerii Engel, who served as editor along with Mark Kupovetskii. The Information Bulletin on Problems of Repatriation and Jewish Culture (Informatsionnyi biulleten’ po problemam repatriatsii i evreiskoi kultury) was published from 1987-90; each of the 45 issues had from 60-140 pages. The editorial board included Aleksandr Feldman, Aleksandr Shmukler, Aleksei Lorenson, Igor Mirovich, Valerii Sherbaum, Eduard and Liudmila Markov, and others. From 1988-89, on the basis of the Moscow legal seminar, the journal Problems of Refusal (Problemy otkaza) was published under the editorship of Evgenii Grechanovskii, Mikhail Gutman, and Georgii Samoilovich.

The Hebrew University’s Centre for the Study and Documentation of East European Jewry collected a large quantity of Jewish samizdat, publishing 28 volumes of material. In addition, it published eight volumes of collected petitions, letters, and appeals of Soviet Jews.

In its development from isolated, often translated, works to periodical publications, the Jewish samizdat reflected the basic stages in the national revival from an underground struggle of individual, weakly connected groups in the 1950s-1960s through the development of an organized open struggle, followed by setbacks in the late 1970s-1980s during the years of renewed repression.

In 1987 the policies of perestroika (rebuilding) and glasnost (openness) led to a sharp increase in emigration (eight times greater than the previous year) and to the revival of samizdat activity. From 1987 to 1989 there was a gradual transition from samizdat to legal publications. Examples of such transitional publications were the Jewish Annual, the Information Bulletin, and Mame Loshn (Yiddish for native language).[17]

The independent publication of textbooks was a somewhat special aspect of samizdat activity. The demand for such material continually increased, and in Moscow alone, each month saw the preparation of hundreds of copies of the textbooks Elef milim and Mori, verb tables, dictionaries, reading texts in easy Hebrew, and so forth. Textbooks were generally prepared by photographing, whereas literary and publicistic samizdat works were more likely to be produced on the typewriter or sometimes by xeroxing. Textbooks (like journals) went from hand to hand and were read until they were worn out. Some people copied over dictionaries and textbooks by hand for their personal use.

The demand for textbooks increased sharply from the start of the 1980s, when Moscow instructors helped develop Hebrew teaching in provincial cities.

Among the many people who played a large role in organizing the preparation and dissemination of Moscow samizdat were Vladimir Prestin, Pavel Abramovich, Mikhail Nudler, Viktor Brailovskii, Feliks Kandel, Eliahau Essas, Viktor Fulmakht, Andrei Brusovani, Vladimir Mushinskii, Zeev Geizel, Grigorii Levitskii, Viktor Dubin, and Igor Gurvich. Several groups worked simultaneously on preparing and distributing samizdat but they worked in isolation from each other so that if one was exposed, the others wouldn’t suffer.

The ongoing process of people receiving visas and leaving affected samizdat production, making it necessary to bring new, preferably not very exposed people into this sensitive and dangerous zone. Today it is not always simple to track down the first person in the chain─the one who found the necessary elements, brought them together, and arranged for steady production.

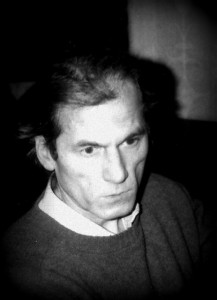

One of those people was a graduate of the mechanical mathematics faculty, a passionate numismatist and talented organizer, Mikhail Nudler. A student of Shakhnovskii and a Hebrew teacher himself from 1973, he organized the system of professional preparation of textbooks that functioned smoothly for almost twenty years.

Misha, how did you get started in samizdat activity? I asked Nudler.[18]

As you recall, Misha began slowly, we all suffered from the lack of textbooks for groups of beginners. We copied them ourselves or one of our students did it, but they were of poor quality and didn’t reach the groups in time. It fwas a problem. I managed to find a professional photographer, a Russian. For a very moderate fee, he photographed and quickly produced any amount of copies.

How did you find him?

I had friends among the bohemians and artists. At some evening gathering, I said to one of them: “If you could only find me a photographer.” “A photographer?” he asked. “As many as you would like,” and he gave me a telephone number. We met this fellow on the street and I explained the matter to him. He said, “Fine, that doesn’t interest me. I’ll do my job and you do yours.” He didn’t want to know what he was doing; he didn’t care whether it was Hebrew or not Hebrew. Just a certain amount of rubles and that’s it. After that, I began to supply all the teachers. That photographer created a library of microfilms and one only needed to tell him which one and how many copies were needed. We always met at the Mayakovskii metro station. He would come with a large bag, give it to me, and receive the money. I remember that Igor Gurvich had to travel to Baku and he needed forty copies of Elef Milim. In two days he received them without any discussion. The fellow was a professional; he had machines for developing and drying and so forth.

Did you also deal with literary samizdat?

Yes, I had a full-time typist. She typed the journals Nash ivrit and Tarbut from 1977 to 1979. I also wrote a bit for Nash ivrit.

Vladimir Mushinskii assembled a production line for samizdat. He worked with Prestin, with me, Fulmakht, and Geizel. Gradually, a large publishing “syndicate” arose under his wing. Mushinskii became involved in the movement in 1976. His long-time friend, the Kiev activist Leonid Elbert, introduced him to Prestin. Good-natured and sociable, Mushinskii knew how to get along with everyone. His keen understanding of human nature and rich personal experience enabled him to utilize the services of people who either were not connected to the movement at all or outwardly did not manifest any link, including a considerable number of non-Jews.

Did you understand, in general, what you were getting into? I asked Volodia.[19]

Lenia Elbert immediately warned me: “What you want to deal with is punishable by seven plus five” [i. e., seven years of imprisonment plus five of exile], Volodia smiled.

After I met you, which was in 1980, orders increased, and my staff of workers expanded to seventy people. There were editors, many typists, a few photographers, binders, couriers, warehousemen, and so forth.

You weren’t afraid?

I thought through everything so that I wouldn’t “stand out” anywhere. Prestin and Abramovich were tailed but our contact was minimal. We usually walked in the Izmailovo forest and reached agreement there. I would bring the finished product to the bus station and place it in a locker for safe keeping; I put a piece of paper with the locker number and code in their mail box.

At some point Prestin introduced me to Grisha Levitskii, who also was publishing something with Geizel. Grisha worked as a stoker in a boiler room and it was convenient to hide everything there. You dug in the coal and that was it. In the worst case, it went into the stove.

Samizdat helped us survive in refusal; it was a breath of fresh air in the stagnant, poisoned atmosphere of the Soviet Union. For many of us it became a window to the larger world extending beyond the borders of the Iron Curtain. For our friends and supporters abroad, it became the voice of the movement, facilitating their understanding of what we were fighting for and the conditions of our struggle. The ideological foundation of the movement was forged on the pages of samizdat.

In 1990 the gates were opened wide and the potential for emigration was understood: departure was limited only by the technical possibilities of OVIR .and the customs. The Jewish samizdat played a worthy role in creating this potential.

[1] Kratkaia evreiskaia entsiklopedia (Jerusalem, 1966), 7:638.

[2] Matvei Chlenov, “Samizdat,” Sbornik materialov Pervoi molodezhnoi konferentsii SNG po iudaike (Moscow, 1997). see also, Stefani Hoffman, “Jewish Samizdat and the Rise of Jewish National Consciousness,” Jewish Culture and Identity in the Soviet Union, eds. Yaacov Ro’i and Avi Beker (New York: New York University Press, 1991), pp. 88-111.

[3] Mikhael Margulis, Evreiskaia kamera Lubianki, (Jerusalem: Gesharim, 1996), pp. 134-135.

[4] Margulis, p. 107.

[5] The Chronicle of Current Events was the name of the democratic movement’s underground information bulletin that appeared in Moscow from 1968 until 1983. In the course of 15 years, 63 issues of the Chronicle were published (Y.K.).

[6] M. Chlenov, “Samizdat.”

[7] Vitalii Svechinskii, interview to the author.

[8] Matvei Chlenov, “Samizdat.”

[9] Kratkaia Evreiskaia Entsiklopediia, 8:270.

[10] Aleksandr Voronel, interview to the author, April 4, 2007.

[11] Viktor Brailovskii, interview to the author, May 17, 20017.

[12] Matvei Chlenov, “Samizdat.”

[13] Dina Zisserman, interview to the author, May 10, 2006.

[14] Pavel Abramovich, interview to the author, May 19, 2007.

[15] M. Chlenov, “Samizdat.”

[16] Mikhail Beizer, interview to the author, April 25, 2007.

[17] M. Chlenov, “Samizdat.”

[18] Mikhail Nudler, interview to the author, May 18, 2006.

[19] Vladimir Mushinskii, interview to the author, January 24, 2004.