After the Brussels conference, the tension between the kulturniki and politiki increased even further. Both, however, decided to test the Soviet Union’s willingness to observe the human rights obligations of the Helsinki Accords: the linkage between the three baskets looked most tempting and serious: recognition of the postwar borders and détente between East and West, scientific-technological and trade exchanges, and─human rights. The kulturniki began preparing a major international undertaking entitled “A Symposium─Jewish Culture in the USSR: its current state and prospects.” The politiki worked to set up global mechanisms for public monitoring of the Soviet regime’s compliance with the Helsinki Accords in the field of human rights─the so-called Helsinki groups, committees, and associations. Jumping forward, I shall mention that the Soviet Union did not stand up under both tests but reacted differently to the two initiatives.

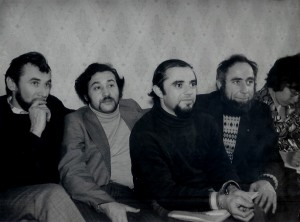

One of the chief ideologists of the revival of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union was Professor Veniamin Fain.

Venia, where did your cultural zealousness come from? Were you engaged with culture earlier? I asked him.[1]

It’s not cultural but Jewish zealotry. I was born into a family where this topic was always present and for me the question: “when did you begin to feel like a Jew?” did not exist. Our family had to flee once, then again, and we always had the feeling that if they would overtake us, it would mean death.

From where did you flee?

During World War II, we fled from Kiev to the Caucasus and then from the Caucasus to Central Asia, stopping in Baku. I knew that I was a Jew, but I didn’t know why this was happening or who we were. In1944, inStalinbad, now Dushanbe [Tajikistan], I went to the library and read everything that was available there on Jewish history but didn’t receive an answer. From that time on, I have been preoccupied with two topics: science and Jewry.

How old were you in 1944?

Fourteen.

Was your father also an academician?

He was a mathematician. He wanted to be one but…. He taught in institutions of higher education.

Later, when I arrived in Moscow, the first thing I did was to appear in the synagogue; I saw the meeting with Golda Meir. I decided to study Hebrew, went to the Lenin Library, and found a book entitled Everyday Hebrew. I visited there every day and read the book. After a week, the book disappeared. I went to the bibliographical section, where a middle-aged Jew was sitting. He asked me, “What do you need that for?” “I want to study Hebrew,” I said. “Let me teach you.” What good luck. When I arrived the next day, he said, “Unfortunately, I can’t do that.” Then I decided to study Yiddish. I went to the editorial office of Der Emes (Yiddish─truth; the official newspaper in Yiddish, Yu. K.). They said to me, “Young man, that is very praiseworthy. Come back in a month and we’ll have all the books ready for you.” I came a month later and saw a strange sight, as if after a pogrom. An old Jewish cleaning lady, said to me: “You don’t know what happened? They arrested everyone.” Then I started attending the Jewish theater. I went there every day to every performance. In a few months, it was closed down.

Venia, but you joined the movement rather late. Why?

There was a family tragedy. In the summer of 1972, my daughter died and that completely unnerved me.

Why did you decide that the cultural trend was so important for the Zionist movement?

The first stimulus came at the end of 1973, when I had not yet applied for an exit visa. The large-scale neshira began and something had to be done about it.

At the end of 1974, I made the acquaintance of Vladimir Prestin. After discussing the issue, we came to the conclusion─and this is important─that Jewish education has a significance for Jews independent of Zionism and emigration. Jews have a right to their own culture, just as they have a right to emigration. One does not contradict the other because when a person acquires a normal national consciousness, then he begins to think about what to do with it. For us, this conclusion was not directly linked to whether or not education would help emigration. That is a separate topic.

You were technicians without the appropriate cultural basis. Why did you decide that precisely you should and─most importantly─could do this?

If the Jewish cultural figures had not been shot and were prepared to take this upon themselves, I would only have been happy to support them with all my heart and not play any visible role. But they were shot…. We thus planned the symposium, speaking loudly about the current situation of Jewish culture and what we intended to do about it.

How did you plan to reach the Jewish masses? Clearly, 150-200 copies of Tarbut were insufficient for this.

We did what we could. The symposium was designed to put the topic on the international agenda.

That’s how you tried to bring the issue to the attention of the Soviet regime?

Them, too, but primarily to the West, which considered that emigration was proceeding, neshira was occurring, and that’s how it should be.

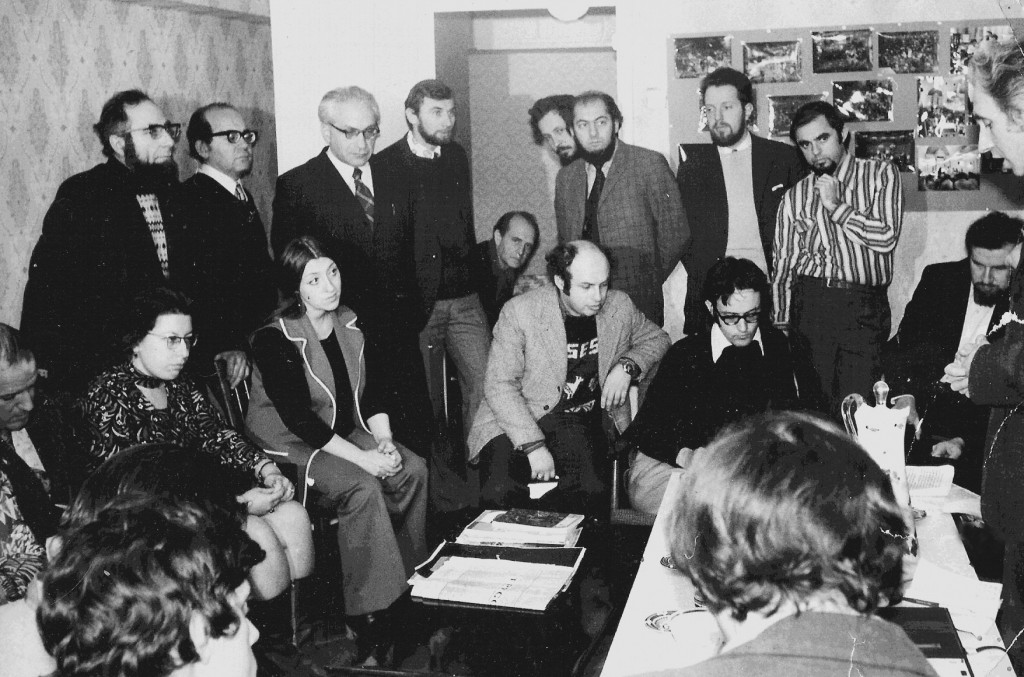

Preparations for the symposium lasted several months. During that time there were intensive discussions on the strategy and ways of developing Jewish culture. The organizers succeeded in involving over one hundred activists from various cities in the Soviet Union and a large number of Jewish scientists and humanities scholars in the West in the work of the symposium. Seventy-seven reports on various aspects of the current state and development of Jewish culture in the USSR were prepared.

Prestin and Fain were not part of your crowd. How did you get involved in preparations for the symposium? I asked Mikhail (Mika) Chlenov, an ethnologist and noted Hebrew teacher.[2]

At the beginning of 1976, I delivered a report at the Rubin-Kandel humanitarian seminar that was attended by the two quarreling groups. On one side sat Prestin, Abramovich, and Fain and on the other─Slepak and his friends. My report, in essence, presented the future program for the VAAD (Hebrew for committee, a Jewish organization that was established in the USSR in 1989, Yu. K.). Everyone listened with interest and when the crowd had dispersed, Prestin approached me and said: “Who are you, where did you come from? I don’t know you…. Stay with us.” That’s how I landed at the first session of the symposium’s organizing committee right there in Kandel’s home.

Subsequently, they invited me to join the organizing committee. I was a bit afraid. They, indeed, were all refuseniks and I hadn’t even applied. I said: “Not as a member of the organizing committee but as an expert for the committee.” I thought that would save me (Chlenov laughs). They said, “We are planning to conduct sociological polls among the Jewish population but we don’t know how to do it.” It so happened that I did know. “As an expert,” I said: “I’ll be happy to deal with that.”

We conducted a poll with questionnaires among acquaintances and relatives, interviewing people in the summer at the beaches, dachas, and rest homes. As a result, we obtained a most respectable quantity of 1200 respondents throughout the USSR. It’s true that it was not a random sample but the results were close to the results of later polls that we conducted professionally in the post-Soviet period.

The poll showed a demand for Jewish culture. In response to the question, for example, “Would you buy a book on Jewish history if it was sold in a Soviet store?” ninety-eight percent answered: “Yes, of course.” There were questions about schools: “If there was a Jewish school, how would you like it to be?” There also were questions about the attitude toward emigration and how they envisaged the future of Soviet Jewry.

What ideas about the development of Jewish culture were elaborated in the process of preparing the symposium?

Four programmatic reports were presented: the main one was signed by Prestin, Abramovich, Tsilia Roitburd, Kushner, and Fain; my report, which in essence was the one I delivered at Kandel’s seminar; and reports by Ilia Essas and Grisha Rosenshtein.

What did the central report with the five signatories propose?

Basically, Jewish culture in the USSR ought to serve aliya and be oriented toward Israel and the West.

What did you propose?

Culture as an independent direction on the basis of a dialogue with the regime.

What was Essas’ approach?

The movement must strive─and in this he saw the future of Soviet Jewry─to create minyanim of a new kind.

What about Rosenshtein?

Grisha Rosenshtein wrote that the future of Jewish culture depends directly on the presence of tsadikim (righteous people) in the Jewish milieu. Those were the four basic reports. There were some interesting things here and there. For example, Lerner, the former head of the politiki, explained why the Jews in the Soviet Union must not get involved with culture: it’s not only harmful but also illegitimate because no one authorized us to act in the name of the Jewish people. He considered the movement for the right to emigrate was the fundamental stimulus for the revival of Jewish consciousness in the USSR and that there were no grounds for a discussion of Jewish culture in the Jewish national movement. Judeo-Christians also applied to the symposium, offering a report about Christianity as a contemporary form of the realization of Zionism in the Soviet Union. Essas objected and did not permit the organizing committee to accept this report.

How can Christianity be a realization of Zionism in Russia?

You have to read the report in order to understand that. Not only in Russia. “All of us Judeo-Christians ought to go to Israel,” according to them. Indeed, they all planned to move to Israel.

The organizing committee consisted of many activists of the cultural movement: Veniamin Fain (Chairman), Vladimir Prestin, Pavel Abramovich, Leonid Volvovskii (deputy chairman), Ilia Essas, Mark Azbel, Viktor Brailovskii, Vladimir Lazaris, Arkadii Mai, Feliks Kandel, Yosif Begun, Yosif Ahss, Veniamin Bogomolnyi, Evgenii Liberman from Moscow, Valerii Kaminskii, Arkadii Tsinober, Boris Frenkel, German Shapiro (Riga), Naum Salanskii, Vladimir Drot (Vilnius), and Semyen Kushner (Baku). The activists’ broad spectrum of views on the revival of Jewish culture in the USSR could be divided into three basic categories: secular Zionist (the reports of Fain, Prestin, Abramovich, Kushner, and Roitburd), religious Zionist (Essas and Rozenshtein), and legalist (Chlenov).

What distinguished the approach of your group from that of Chlenov? I asked Vladimir Prestin.

We assumed that we could organize educational-cultural activity on our own with the support of Israeli and Western Jewish organizations. An indispensable condition for this was the regime’s non-interference.

What made you think that the authorities of a totalitarian state would agree to farm out such an important part of its brainwashing activity?

They wouldn’t do so voluntarily. We had to fight for it with the support of our Western friends. You see, we were not so naïve as it might seem at first glance. For the first time in the Soviet period, the question of human rights became a political issue. I mean the Jackson-Vanik Amendment not Helsinki. The country realized that it would have to pay dearly for violating certain of its citizens’ rights. Second, of course, was the Helsinki process. Did we really want so much? We were trying to revive the culture that had been crushed and destroyed by the Soviets. Mika (Chlenov) asserted that one couldn’t get around the Soviet regime and that one had to cooperate with it on cultural issues; otherwise, nothing would come of it. The totalitarian Soviet regime, however, couldn’t become democratic overnight and start to cooperate with us even if Chlenov wanted it. In reality, only after the disappearance of the USSR did the new regime recognize the Jews’ right to national education.

Chlenov’s approach seemed too revolutionary and fantastic for its time. His viewpoint was unacceptable to the majority of activists. No one, of course, would object to the free development of Jewish culture in the Soviet Union but we did not believe that the antisemitic and anti-Zionist tyrannical state would ever cooperate in the development of truly normal Jewish culture. Many activists, including myself, thought that the Jews did not have a future in the Soviet Union and that anyone who wanted to remain a Jew should go to Israel and live a normal national life there. Without denying its value, we considered that culture ought to serve aliya and prepare people to return to their people and for life in Israel.

What, in essence, was Chlenov saying? That aliya was a very important, but not sole, element in the solution to the problem. That we ought to remember those who remain in the Soviet Union, that they could be reached only by legal culture, and that it was necessary to exert pressure on the regime and try to reach an agreement with them to permit such culture. He saw the future of those Jews who would remain in the USSR in the revival of a national culture that would not intimidate or repel them.

This sounded, at the very least, untimely. But the years would pass, the Soviet regime would weaken and disappear, and Chlenov would succeed in realizing his program. About a third of the Jews, those who remained on the expanse of the former Soviet Union, received the freedom to develop a legal, autonomous Jewish culture that he had dreamed about in the mid 1970s.

Extensive preparations for the symposium were carried out. “We decided to do everything completely openly,” wrote Fain, “in full accordance with the Helsinki Accords…. We planned very carefully and thoughtfully. ”[3] The committee solicited participants from within the country and abroad, describing the approximate range of topics for the reports and indicating that they would be accepted until November 15, 1976.

Dozens of invitations were sent to representatives of the regime, local and foreign journalists, highly-placed officials in the ministry of culture, scientists, and prominent rabbis. “The announcement about the forthcoming symposium, noting the dates it would be held, was broadcast by the Voice of America, the BBC, and other Western radio stations. At first it was scheduled for December 19-21, but then we decided to delay it by two days. We remembered that December 19 was Brezhnev’s birthday, and we didn’t want to give the authorities a pretext to declare the symposium a provocation.”[4]

How did you envisage the revival of Jewish culture? I asked Fain.[5]

Unlike Chlenov, we said to the authorities: “Let us do things on our own”. We foresaw, however, a gradual process that would entail, for example, a journal under UNESCO’s aegis devoted to Jewish culture that would be accessible in Russia, something similar to the journal America. A struggle for the legalization of Hebrew. That is, we intended to begin with small steps, gradually expanding our sphere of activity.

Did you want to legalize culture with the help of the West, utilizing the Helsinki instruments?

Yes, we wanted open access to culture in the West but we didn’t want the regime to create culture that was Jewish national in form and socialist in content [which was the formulation that the Soviet Union tried to impose on all minority cultures]. We wanted genuine culture.

What was your attitude toward the politikis’ contention that attempts at a broad revival of Jewish culture would deflect significant forces from the aliya struggle?

Nonsense. Because a person feels himself a Jew, would that reduce his motivation to leave for Israel?

Invitations to participate in the symposium were sent to forty prominent Jewish cultural figures in the West, including Elie Wiesel, Salo Baron, Gershom Sholem, and others.

The program included 77 reports divided into six sections:[6] the state of Jewish culture in the USSR; the role of religion; new breeding grounds for the shoots of Jewish culture in the USSR; Jewish culture in Israel and the West; a characterization of Jewry; prospects. Among the most noted Western figures sending reports were Salo Baron; Nahum Goldman, chairman of the World Jewish Congress; and Rabbi Adin Shteinzalts.

I asked Leonid Volvovskii, deputy chairman of the organizing committee, about the organizational work of preparing the symposium.[7]

Many of us had organized dozens of symposiums in our lives, but in those cases we understood what we were organizing. This time, however, we wanted to organize a symposium on a topic about which we understood nothing. The main task of the symposium consisted of stimulating public opinion around the world and drawing attention to the fact that Jewish culture was suppressed in the Soviet Union.

I don’t understand. You intended to develop Jewish culture or to raise a worldwide hullabaloo, to arouse a wave of protest so that the authorities would feel the heat and let you go?

It was understood that none of those present could really advance culture. We only taught Hebrew, Venia Fain edited a journal, Volodia Prestin wrote some articles and Pasha Abramovich edited something─that was the entire culture. For us, however, it wasn’t a matter of hopping a ride on this and leaving the country. We hoped that under the pressure, the regime would allow some center of Jewish culture to develop. We pondered for a long time and drew up a plan. Then we compiled a list of names from newspapers and personal acquaintances and prepared letters. Although we understood that we would get nowhere with Soviet figures, we had to observe the niceties and sent invitations to Soviet organizations. We also sent invitations abroad, thinking that one or two answers would arrive, but then they began to stream in. We asked people to send the basic theses of their talks and these began to arrive in a large quantity─not through the mail but someone would bring them in. From the Soviet official side a sepulchral silence reigned. We also began to prepare materials. Our basic task was to organize a sociological poll.

That’s what Chlenov did?

He prepared the questionnaire. Everyone took part. I took on responsibility for gathering all the data that needed to be processed. It turned out that conducting a poll in the Soviet Union was a terrible criminal act. The first signals from the authorities came in November─we received an invitation from the Yiddish newspaper Sovetish Heimland. Pasha, Volodia, Venia, a fellow who knew Yiddish, and I went. Vergelis [the editor-in-chief] came to meet us and began to speak in Yiddish. We stood there. As soon as he finished, we all began to speak in Hebrew. It was their turn to be silent. Then one of us said: “Well, the performance is over; now let’s speak in the language that we all know.” In truth, they did not want to speak with us about anything. They kept directing the conversation to our supposed plan for an anti-Soviet action that could harm everyone. We kept on evading that topic and asking about the development of Jewish culture in their milieu, about the number of young people who were involved, and how they spent the holidays. “What holidays do you observe?” I asked. Vergelis got up and replied: “We Soviet Jews have only one holiday─the day of the Great October Revolution.”

A half hour after the meeting, this sentence appeared in all the Western media. It was a blow for them. After that, we prepared for any emergency─with bags that contained an assortment of underwear and the necessities in case of arrest. We subsequently received an invitation from Vladimir Popov, the first deputy minister of culture of the USSR, who was also a member of the Politburo. We arrived with our bags and were checked. Two people were sitting with Popov. He began to speak and we asked him to introduce himself, which he did. We asked innocently: “And who are these respected people next to you?” Popov replied: “Directors of divisions….” And I see that the hands of these “division heads” are itching to speak with us in their way (Volvovskii laughs). Popov began to speak: “What you want can’t be done. There are, of course, problems, but, on the whole, the situation with regard to Jewish culture here is good. We have so many Jewish musicians and playwrights.…” He paused to think for a moment and added: “Yes, what’s there to say─all of them!” We all record this. Venia replies that, of course, these people are Jews but they have nothing to do with Jewish culture. That is Soviet culture, and we want the language, history, and Jewish theater. Popov says: There are Jewish schools in Birobidzhan and the language is studied.” Venia answers: “We inquired at the regional board of education of the Jewish Autonomous Region with regard to Jewish language instruction,” and he reads: “No Jewish language has been taught in the Jewish Autonomous Region since1947.” Popov had nothing more to say other than that our undertaking was anti-Soviet.

We did not receive any further invitations, but they began to tail us actively. This was followed by searches of all members of the organizing committee and others who were involved in preparations. On the eve of the symposium there was an unpleasant incident. Tsilia Roitburd called me and said that she could not keep symposium material at her place and asked that I take it. This was by telephone! I took it and on the following day there was a search at my place and everything was taken. Fortunately, it was not the sole copy. In such cases it’s difficult to conceal everything. The telephones of all members of the organizing committee were disconnected. Even the public telephones in my area were not working.

Only one of the foreigners invited to the symposium succeeded in arriving in Moscow─Rabbi Rabinovich from Maaleh Adumim in Israel, who, at the time, was teaching in Jews’ College in London. He traveled to Venia Fain but at the subway exit, two men approached and said: “You can’t go any further.” He rode to me, got out at Chernigovskii Street and was told: “No further.” And from there to me it was still several kilometers. When we met during the week following the symposium’s planned opening, he said: “You achieved your goal; you even surpassed it.”

On the morning of the symposium, my wife Mila got up and saw that our little street looked like there was a May Day demonstration. Crowds of people were strolling. I had no idea who they were. We took our bag, went outside, and “they” immediately pounced on me. I was taken to a police station, registered, and taken home for a search. When my daughter went outside as if to take out the garbage and phoned to an agreed upon number of a friend, a KGB officer picked up the receiver. Every day I was taken to the police and interrogated by an unhappy figure, Smirnov. He wrote: “Who told you to conduct a symposium and when?” I wrote: “I don’t understand your sentence.” A cat and mouse game. Then, in the evening I said to him: “It’s Hanukah now and I must light the Hanukah candles.” I took out candles from my pocket and lit them. The next day at five o’clock, he himself said: “Candles.” And thus it continued for a whole week. He already ran out of questions and I didn’t give him any answers.

Mikhail Chlenov conducted himself similarly at interrogations. He told me:

Blatant harassment began in November; they carried out searches and began to confiscate sociological questionnaires, which, for some reason, they hunted for intensively. There was a computer operator named Oskar Mendeleev who transferred everything onto perforated cards. It produced a roll with a series of figures. “They” got to Oskar, too, and to the computer on which he did all that at the institute. There were two copies, however, that remained. Fain managed to send one somehow to the West; later on, a booklet was written using it and another copy remained with me. On the day of the symposium, the KGB grabbed the entire organizing committee, including me. On the eve, my telephone had been disconnected, and it didn’t work for the next two and a half years. For a whole week they tailed me closely; there were four Volga cars standing by the corners of the building. In the morning, I went out to make a call, stopped at a public telephone, a car drove up, and took me in hand…

Were you ready for such things, Mika? After all, you didn’t plan to leave.

What do you mean, “didn’t plan”? My wife didn’t want to go. And I had the choice of either breaking away from my family with three children, which didn’t appeal to me, or hoping that perhaps with time I could convince them. All my life I wanted to leave…. I was put in a car and taken to a police station. I asked: “What’s going on?” They: “There are rumors circulating that you don’t like the Soviet regime.” “Who told you that? What nonsense. And what does the Soviet regime have to do with this? Where have you brought me?” They said softly: “Now we’ll go to your house.” They brought me home at nine o’clock in the morning with a search warrant, and the search continued until midnight. As it turned out, there were four people whom they pursued to the maximum─Abramovich, Fain, Volvovskii, and me. My unwillingness to be a member of the organizing committee didn’t spare me.

Early the next morning they came for me with the cops, and in front of the entire house they led me out with my hands behind my back for an interrogation. When I reminded them that they needed a summons, they casually waved me off: “Yes, it’s all right.” They held me and interrogated me until the night─and thus it continued for a week. I immediately declared that I would answer only in writing.

Using Volodia Albrekht’s system?

Naturally. In general, I stirred things up a lot. They didn’t let me out to eat and brought in some kind of yogurt and roll that I was forced to eat, but each time I wrote a protest that I didn’t want to be on their upkeep. I tried to slip them money but they wouldn’t take it. In general, I began to feel that I had gotten into quite a mess….

What happened on the opening day of the symposium?

The kulturniki were detained and couldn’t get to the “hill” near the synagogue where Grisha Rosenshtein was supposed to meet everyone and lead them to his apartment, which was a big secret. Even I didn’t know our destination. The audience arrived but not the participants. Shcharansky brought Sakharov. Perhaps that’s why the authorities didn’t have the nerve to disperse them directly on the spot. A few people by chance had the theses of a couple of reports.

Taking into account that they might be arrested, the organizing committee prepared a letter in advance that was hidden in Yosif Begun’s apartment. The hiding place was in the handle of a mop. The letter was called “the testament” and in case of arrest, it was supposed to be removed and publicized. Only two people knew where the letter was hidden─Lena Dubianskaia and Mara Balashinskaia-Abramovich. When it became clear that the organizing committee had been arrested, the two women took the letter out of the hiding place and read it aloud at Rozenshtein’s apartment, where people had gathered for the symposium.

The symposium as such did not take place, Chlenov summed up for me. Pro forma, the theses of several reports, each half a page, were read aloud, followed by a political meeting. Those present protested the detention of their friends.

The regime, evidently, was not ready for a dialogue. There was a group of liberals among them but at that time the so-called “Russian party” gained sharply in strength. Andropov, incidentally, was not a liberal. In fact, he advocated a hard line with regard to any dissidence.

In the first months that I was busy with the sociological poll, the organizing committee was not bothered. That is, during the entire period between the start of the year and October, the authorities were thinking things over. At that time they decided: “No.” And they began to prepare two trials: one for the cultural and the other for the political group. Shcharansky told me that he had information that a trial of the kulturniki was being prepared and I would play a central role in it. Things turned out just the opposite. Three months later, he played a central role in a trial of politiki.

Although the authorities did not let the symposium take place, they acted with some restraint.

Volodia, I said to Prestin, they disrupted the symposium and confiscated the material. Several people were dragged in for interrogations and they were not so sure that things would end well for them. Some participants in those events assumed that the regime was planning two trials, against both the cultural and political wings. In the end, they selected the politiki and in 1977 heads began to fly.

You know my attitude toward that terminology. There were no kulturniki. We did everything and for everyone.

Understandably, it’s an arbitrary division.

I can’t speak about the regime’s intentions. I, however, do not agree with the evaluation that the symposium was completely disrupted. During the searches, part of the material was confiscated but we managed to preserve absolutely all the reports and we published them in samizdat. It’s true that the regime did not allow foreign participants to arrive in Moscow or permit us to conduct a normal session of the symposium. By their behavior, however, they only highlighted their own policy of suppressing Jewish culture in the USSR. The disruption of the symposium was widely publicized on the first pages of many newspapers in the democratic world. The materials comprised a broad program for us and for our supporters in the West. Reviving Jewish culture became an essential component in our life.

In general, I presumed that, given the lack of freedom in our life, undertakings that were limited in time were more viable than any kind of ongoing committees or working groups, which is why a symposium was chosen. And the symposium, which you called “disrupted,” nevertheless provided a powerful spiritual charge for the Jewish national revival.

In your view, how did the cultural process develop further? I asked Mika Chlenov.[8]

I would call the years 1977-80 the period in which the Jewish cultural movement in Moscow flourished─and not only. In the summer of 1977 we got together and tried to figure out what to do next, the more so because the crushing of the political movement occurred at that time. … In the summer, suddenly Jewish youth began to appear as a result of this very symposium … and initiated song festivals, Purim spiels, and many other things that didn’t exist previously.

It should be noted that the politiki ignored the plans for the symposium and did not participate in the preparatory work. Moreover, they openly and rather widely expressed their negative attitude to the undertaking as diverting significant forces inside the country and abroad from the basic task of the Zionist movement─the aliya struggle. An exception was Anatolii Shcharansky, who helped to get in touch with foreign correspondents and brought Andrei Sakharov to the aborted session. Dina and Yosif Beilin also attended that session. After the session, those who were present composed and signed a letter of protest against the arrests and held a press conference.

With regard to Israel’s position in this ideological stand-off, each group thought that Israel supported the other one. I turned to the former head of the Liaison Bureau, Yakov Kedmi, for clarification.

Yasha, I had the feeling that Israel did not support either group. The establishment treated the Soviet Union as a reservoir for aliya and supported only the factors that reinforced aliya: Hebrew, Zionist material, positive information about Israel.

We ourselves worked a lot with Western politicians. We needed their support for aliya. We considered that the methods of the political wing inside the Soviet Union were dangerous, first of all for them, which was confirmed by further developments. You are right, on the whole, that, on the one hand, people who were in refusal for years had to do something, otherwise one could go crazy. We supported the forms of activity that were less dangerous for refuseniks. Culture that was oriented toward aliya was both useful and less dangerous.[9]

Veniamin Fain, chairman of the symposium’s organizing committee, did not see a dichotomy between the aliya struggle and the cultural one. “They must go hand in hand,” he wrote, “because they reinforce each other.”[10]

[1] Veniamin Fain, interview to the author, June 22, 2008.

[2] Mikhail Chlenov, interview to the author, January 31, 2004.

[3] Veniamin Fain, Vera i razum, p. 229.

[4] Fain, Vera i Razum, p. 231.

[5] Veniamin Fain, interview to the author, June 22, 2008.

[6] A list of the reports prepared for the symposium are listed in Evreiskii samizdat, vol. 15, published by the Centre for Research and Documentation of East European Jewry of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1978), pp. 20-23.

[7] Leonid Volvovskii, interview to the author, April 4, 2006.

[8] Mikhail Chlenov, interview to the author, January 31, 2004.

[9] Yakov Kedmi, interview to the author, July 6, 2004.

[10] Fain, Vera i razum, p. 245.