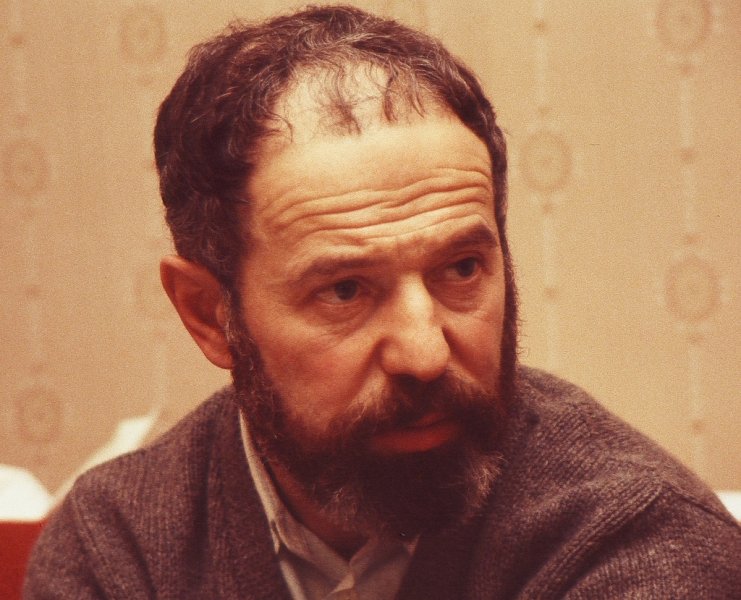

Interview with Anatoly (Nathan) Schwartzman, January 14, 2004.

Together we are flying to Moscow to the 15th Anniversary of the Jewish Renewal in the U.S.S.R. It is sort of noisy but still quite possible to talk on the El-Al plane. The goal of the trip was conductive to reminiscences. I begin my interview.

Y: You are one of the main organizers of one of the most interesting institutions of refusal, Ovrazhki. This is going to be the main issue of the interview. But first tell me about yourself. Where and into what kind of family were you born, was there anything Jewish in the family?

N: I was born in March 1929. Because my father was a «lishenets» (“deprived” person), I was born in Nizhniy Novgorod in spite of the fact that my parents were Muscovites. In 1929 the attitude to the “deprived” became more lenient and they returned to Moscow, to the Moscow region, actually. This was the beginning of my life and now I switch to the moment immediately preceding my aliyah. I worked in a top-secret institute in a rather high position of Leading Engineer.

Y: What kind of an institute was this if I may ask you?

N: You may. Once, before I started to work there, it was the famous Scientific Research Institute of the Fifth Chief Administrative Office of the Army, so all the department heads there were military men. Afterwards when all the secret enterprises were assigned P.O.B. numbers, the institute was called Scientific Research Institute #2377, and then, when such names were no longer considered proper, they invented a civil name – the Moscow Scientific Research Institute for Automated Instruments. The Institute worked in the field of anti-aircraft defense, radars for detection and tracking of aerial objects, such as air planes and in the recent years also missiles.

Y: What are you by profession?

N: My field is automatics and telemechanics, automation devices and systems. My specialization when working in this institute was radar systems. I worked there for 14 years. The process of dismissal and looking for another job continued for about 2 years. I was told that on the meeting of the institute’s academic council somebody said: «Now, when Schwartzman is gone, nobody will continue his line of research». This line of research I formulated and developed myself, and it was detection and troubleshooting in big systems.

Y: It is high time to switch to the Jewish topic.

N: Yes… I have to say that the idea of leaving the country was penetrating into my consciousness very slowly. My life was more or less trouble-free, my hobby was hiking – both short and long trips. There are great possibilities for people with such a hobby in Russia. All my vacations I spent hiking, and after my son was born, we were already canoeing [with him] when he was six. When the first thoughts about leaving the country appeared on my mind, my wife was against it. I decided to leave my job and find a non-secret one instead, in order to remove the “security considerations” barrier from our way to emigration. But looking for a job turned out to be a rather complicated business for me. My list [of potential employers] reached 50. I, an employee of a prestigious institute with the white buildings, sent my resume fly-by-night companies located almost in barracks. Number 50 on my list was the Computer Center of the Central Offices of Vegetable Industry where a certain Julian Hasin whom I did not know until then, had been appointed Head of Department a few months before my arrival. He also left his P.O.B. 3100 where he defended his Doctoral Thesis but it did not work out for him there … and he left. He did not think about emigrating at that time.

Y: When was it?

N: It was on July 26th, 1973. I was already 54 in 1973, and I was hired as Computer Programmer, not as System Analyst, because this is what they needed then. Julian Hasin’s shrewd wife told him at home: «Who are you hiring, he is only applying for this job in order to emigrate». But Julian made little of this. It should be mentioned that there were very many Jews in this place. Russian dissidents, for example, the prominent Sergey Khodorovich who was Solzhenitsyn’s Fund Manager at some point, were there also. And so, for the first time ever I found myself in the environment which on the one hand took an interest in Israel and on the other hand was dissident. So at that place I was not making so much progress professionally, but rather socially.

Y: Were dissident affairs a very near concern of yours?

N: Oh, no. It was interesting to me, but I did not have any desire to get involved in their affairs.

Y: Did you come from an assimilated family?

N: Oh, yes. It would be enough to tell you that when I first happened to be at Zhenja and Galya Zirlins’ home and saw a mezuzah, I asked what it was. They explained it to me. And my notions of religion were very naïve. I once took liberty to say that Mashiakh has come over already, this was the State of Israel. They just laughed at me because Mashiakh could not be a state. I made a vow to myself to work in a civil environment for three years minimum and to apply for exit permit only after this period. I had a hope, I understand now that is was very naïve, that they could grant me my exit permit in three years. Two and a half years later, in January 75, I applied for an exit permit. It so happened that right after having applied I turned out to be at the “gorka” [literally “the hill”, the name for the meeting place of the Jews by the synagogue in the Arkhipova St.] near the Synagogue, met some people there and incidentally met a person from my previous job, a certain Grisha Rosenstein, who quit that place several years before I did. He was a mathematician and used to work at the Theoretical Department that occupied a separate building but he used to have some working contacts with our department. When he saw me he exclaimed: “Well, people from this institute are already coming here, so the situation is good “. Then I learned about one more person from Moscow Scientific Research Institute for Automated Instruments, Alik Joffe. He was also a pure mathematician and also quit the Institute before I did. But I applied for exit permit before he did, and it was me who gave him advice on how to submit the documents for exit permit application. At some point I met Pavel Abramovich, and he asked me where I had worked before. When I told him about the Institute, he said, maybe joking, and maybe not: «You’ll not be able to leave the country for 15 years». And it turned out to be totally true, I left the U.S.S.R. precisely 15 years later. Now when we see each other he reminds me of that.

Y: How did you come up with the idea of Ovrazhki?

N: The idea to get together in the woods had already existed. There was Lunts’ clearing in the woods but the first time I got there I realized it was very inconveniently located. You could get there by bus only. This was in the South West district of Moscow. If there were many people, buses were overcrowded, and they often did not stop at the bus stops where our people were waiting to be picked up. And when the K.G.B. got wind that in certain hours many people got out near that clearing in the woods they just gave order to bus drivers not to stop near it and people had to walk a long distance to that place with kids and backpacks. As an experienced hiker I realized that we had to choose some other place where we could get by commuter train. Besides, we did not want to get too far into the woods. I complained about the inconvenience of the place and they told me to choose another one. My wife and I had several favorite places for hiking in the Ovrazhki district. We walked through the length and breadth of those woods. The pine woods, the beautiful air. One clearing was our particular favorite but my wife said: « That really will be too much! Numbers of people will flock to the place and we’ll lose it». Then I talked to Lyova Kanevsky and he and I rode along many places near the rail road on his motor scooter on our days off. We were still not able to find anything suitable. After all, the place had to be far enough from populated areas and at the same time to be close enough to a train station because it would be too tiring to walk more than three kilometers with kids and things. It had to be surrounded by woods and the clearing itself had to be considerably spacious and light. So I had to talk to my wife again and to ask her sacrifice our favorite clearing. Lyonja Volvovsky worked on this together with me. I told him about my choice and he totally relied on me in this issue. Afterwards we saw that many people really liked this place. At that time I did not of course imagine the scale it would reach.

Y: You planned to get together on Saturdays, Sundays or festivals, was it somehow linked to the Jewish calendar?

N: I can not say there was any particular plan in the beginning. The plan was gradually developing in the process of action. At first I was preparing the place very thoroughly. My wife and I used to come there on Saturdays to prepare everything, and the general gatherings were scheduled for Sundays. It took us the whole Saturday to complete all the preparations. We marked the logs that were suitable as seats and when on Sunday people started to arrive we took those logs together to the place of the gathering. In a certain place in the clearing we made sort of a hovel and it created such a cozy feeling. We also brought there long sheets of paper that were thrown away in quantities at my work. We used them to make improvised tables on the ground. It came out very nice and cozy… People used to come over with guitars, they sang, they told stories… The first gathering took place either on May 1st or on May 9th, 1976. Since that day we met there every two weeks. The place was becoming more and more popular, and it was already impossible to announce our gatherings by word of mouth to such a number of people. I typed the route, the time table of morning trains and the time of the next gathering on narrow strips of paper and handed them out to several guys at the “gorka”. The guys were distributing them to other people. I did not have to explain anything to anybody, things went fast and smoothly. The train time table did not change in summer, so there was little to add to those ads. And very soon everybody knew that which trains we were usually taking on Sunday mornings, and that we were sitting in the first several cars of the train – the way to Ovrazhki began at the head car of the train. Lenya Volvovskiy dealt with the content of the meetings – lectures, speeches, performances. When we realized that a lot of people were coming, we decided to invest more in the agenda of the meetings. We began to organize song festivals. It was Zhenya Liberman who proposed the idea of festivals. In all, we have organized and conducted four song festivals. The last festivals that gathered the greatest audience were hosted by Zhenya Liberman and Mark Lvovsky. According to our estimates, about 2000 people gathered there for the last song festival.

Ovrazhki was restored in Israel as meetings of ex-refuseniks and their families. A poem was circulating that was dedicated to Ovrazhki and had been written still in Russia. At that time an award was conferred to its author on a song contest but he did not show up to receive it, he probably got scared. Now music to the poem has been written and when we opened the monument dedicated to Ovrazhki in the Ben Shemen forests this song was performed. This song reflects the mood prevailing at Ovrazhki at that time. One more idea came up, to organize maccabiadas on Lag Baomer and we used to organize them on a regular basis starting from the second year of Ovrazhki. There are many photographs that remained from these maccabiadas. You can also be seen in many of those photographs. For a maccabiada, some sporting equipment was required. I did not have a lot of money – after I left my secret job at the “P. O. B”, I ended up earning a half of what I had been earning there. This was why I used to buy all the equipment in second hand shops, at give away prices. These were volleyball nets, balls, chess-clocks, chessboards, badminton nets, and I made the borders of the recreation ground with the ropes.

Y: When did you leave?

N: I stepped on the soil of Israel on December 1st, 1988.

Y: That means you were involved with Ovrazhki for 12 years. Was Volvovsky alone in charge of the program content or somebody was helping him out?

N: At first he was dealing with it alone and he alone was moderating those gatherings. Misha Nudler was helping him and you can see this in the photos in which they host a program together. Then Volvovsky became more involved with performance, so I asked other people to prepare lectures related to certain topics. In this way the lectures on Jerusalem were prepared. Volvovsky invested very much in Ovrazhki but then he was exiled to Gorky and his participation in Ovrazhki stopped. When all this just began, I was still a novice member of the movement and I did not yet know the system of relations there well enough, and therefore I consulted other people often. So once I remember asking Dina Beilin how to proceed and who would run it now.

She looked at me from the height of her stature and after some pause said: ”This is up to you”. Being naïve and having the Soviet mentality I believed that there was a ruling hand somewhere, a center. These were mistakes of a person who had just joined the aliyah. At that moment I thought: “Really, why do I have to ask anybody, I will organize everything myself. I will do what my imagination tells me to do”.

In this way I started organizing sporting events, with the appropriate equipment… I did not aim at delivering lectures myself. My goal was to get people involved.

Y: When did you feel yourself a Jew for the first time?

N: This question is beyond the previous topic. As a matter of fact I come from a very Jewish family and I always had a strong Jewish feeling. My mother and my father were from Ukraine, they spoke Yiddish fluently, they corresponded in Yiddish. Therefore in a sense the question is not legitimate. I felt Jewish my whole life, although I did not invest much in this.

Y: Well, and what did it mean for you then? You knew neither the language nor the culture…

N: Yes, in this sense, formally, yes, but I always felt myself a Jew in my soul. I never had any doubts whether my wife should be Jewish and this alone lets you understand my serious attitude to Jewishness. My friends’ circle was Jewish in college and in later years. And now not only I but my children and even my grandchildren have a very integral attitude to Israel. Never, even in the most difficult moments, did we have any regrets about having come to Israel. Our absorption was a complete success in this sense.

Y: But most probably you have had your share of bad things, haven’t you?

N: Of course. Three years and a half I cleaned the streets in Lod.

Y: How old were you when you arrived here?

N: I was sixty and I did not know a word of Hebrew.

Y: Your Hebrew is not so bad now.

N: I can speak easily on easy topics. It is still more difficult to speak on difficult topics. I nave been studying Hebrew constantly and am studying it now too. A retired man is teaching me, he is about 80 already but his head is absolutely clear. Besides, I listen to Podolsky’s lessons.

Y: Did you do anything else besides the street cleaning?

N: You understand my health condition determines to a considerable degree my state of mind. I am doing sports. When I was asked what I was doing in the period of my cleaning the streets I used to answer that I was making Erets Israel clean and beautiful. This was my attitude.

Y: Did your son Dima come to Israel after his graduation from college?

N: Yes, and he had even worked there after his graduation. Here he was hired at BEZEK. I can say that he has made a successful professional career here. He has already had two sons and a daughter. They live in the same neighborhood where we and the parents of Dima’s wife Julya Lurye live. My grandson, a Zionist in the fourth generation, takes an active part in arranging the meetings in the park called “the Israeli Ovrazhki”. He prints out invitations and letters on his computer. Eli Valk gave us many books published by Aliyah Library to help us pay back our expenses by selling them. So my two grandsons Daniel and Jonathan and their friends managed to sell the books. At the ceremony of unveiling the monument in the presence of MK Yuri Stern and other important persons my wife thanked all those who helped us. Among other people, she mentioned our older grandson who did a lot for arranging the meetings and raising the funds.

Y: Here we are flying to the 15th Anniversary celebration. What do you expect from this meeting?

N: I have many hopes for this meeting. Looking back I see that during the refusal time many different activities were developing in the aliyah. There were several seminars: historical seminar, legal seminar, religious seminar. There were Ovrazhki, song contests, there was our struggle. We must not allow this glorious page in the history of our people to be forgotten when our generation is gone. Young people do not know anything. After all, this refusal period is the second such period in the Jewish history considering the Pharaoh’s refusal to be the first. And it was of the same scale. My grandchildren know. I tell them. We have everything – a great amount of photographs, records, movies. But I want others to know. I want the young people to know. And here I encounter lack of understanding and underestimation of this phenomenon even in well known activists of refusal. They already cannot make their children interested in the history of the refusal movement, its struggle, various activities, and it can repeat in the future history of the Jewish people in the countries of Diaspora, and the Soviet refusenik activity experience may prove to be of use. I want the next generation to know about the struggle of refuseniks and their names. Now Aba Taratuta collects materials for the archive, and Zhenia and I help him. Wherever abroad we go, we collect materials because people begin to throw it away. So my activity is not limited to the Ovrazhki issues. When I learned that Aba launched this project, I told him: «Still dim, through crystal’s magic glass I saw the archive’s far horizon» [a reworded quotation from Pushkin’s “Evgeny Onegin”]. I mean that my idea of the magic crystal is the personality of Aba Taratuta, a man of great depth, devoted to the cause, and Edward Markov, such a valued companion-in-arms beside him, too.

Y: Thank you, Nathan.