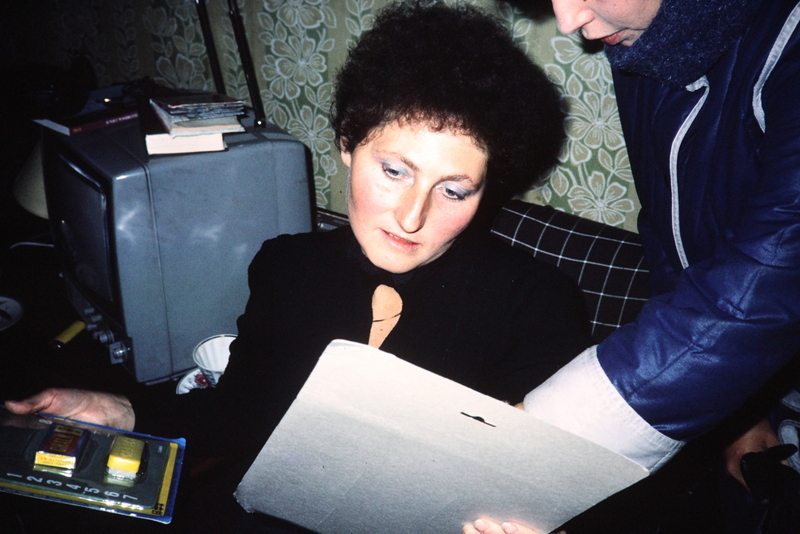

Interview with Tania Edelstein–Feivert. January 27, 2004.

We are sitting in the living room of our house in Beit-Arye, drinking tea and remembering the old days.

Y: Tania, tell me where and into what kind of family you were born and what brought you to the Zionist ranks.

T: I was born in a small town of Cherkasy where many Jews lived. This is near Kiev. My mother had been always living in Cherkasy and my father was a military man, he came over to Cherkasy and…

Y: And where was he from?

T: My father was born in Zhitomir and lived in Kiev afterwards. He fell in love with my mother in Cherkasy… And he was a bachelor in great demand, being a good-looking guy, and girls were after him.

Y: In which rank was he?

T: I do not know in which rank he was then but four years later he was discharged from the army in the rank of captain.

Y: In what year was he born?

T: In 1926. He and my mother have been married for 55 years already, thank God. Now he is 78. When he got married he was about 23.

Y: This was called bachelor!

T: This is how they look at it now. Military men married very early in life at that time. He served in the Air Force as flight navigator.

Y: Did he fly?

T: He did, he was flight navigator, radio operator and gunner. My mother was a very beautiful, curly woman. They got married… I was born in the middle of the century, at noon in June 1950.

Y: Is this an omen of a kind?

T: I do not know… I tried to get my astrological card reading, it came to something rather complex, there was enough of everything, complications as well as joys. Father was sent to the Kurils and Mother was already very much pregnant. She was even offered to leave to the Kurils earlier in order to give birth at the new place. But she did not like this idea and I was born in Cherkasy. When I was only two months old, my parents left from there and I never set eyes on Cherkasy again. Then for one month and a half we were traveling to the Kurils and arrived there on the island of Kurup right after this island was passed over to the Soviets.

Y: So, this was how you became an aggressor since your childhood.

T: There were mainly rats there, swarms of rats. But the place was very exotic. In winter we were so swamped with snow that we had to dig the house out from the snow, and in summer they went to the woods to pick up berries. I myself do not remember anything. We left when I was 5. My father was transferred to the Leningrad region. But there was then the Party purge in1953, and he was given some forms to fill out. Being an honest Communist he wrote that he was born in Zhitomir where all the archives had burned down during the war. This was why they issued his documents in Kiev. And then a typical Jewish story happened. The authorities checked up with the Zhitomir Archives and it turned out that among 10 percents of the archives that survived there was my father’s birth certificate. According to this certificate my father was not Aleksandr Semyonovich as it was written down based on his words in his documents issued in Kiev but rather Shaya Simhovich. He did not have a slightest idea about that himself… When at the age of 30+ he saw that he was Shaya Simhovich, I believe he must have had a heart attack. He was a Communist, a Party organizer and it turned out that he had forged documents.

Y: Was this in 1954?

T: Yes. They summoned him to a Party meeting and told him: “Here, tell the truth to the people how you wanted to conceal your real name from the Party…

Y: To conceal his Jewish origin?

T: No, it was recorded that he was Jewish. But the name was different. He tried to explain them that Shaya was Shurik and Shurik was Sasha, and Simhovich was Semyonovich but the Soviet People was a very tough people so he received a severe reprimand as a Party member. And it was clear that with such documents he could not be transferred to a normal place. He was sent away to a construction battalion. From his flying unit he was sent away to a construction battalion around Leningrad. The moment he arrived there he called Mother over the phone and said: “Either you are coming over to me here or I’ll leave the Air Force as I am being offered to”. And Mother had just moved to the continent [from remote islands], she started to go to concerts, [had a good] life there. Mother said: “What, do you offer me to go to a small place near Leningrad after the Kurils?” And my father’s character was tough, like mine… He left everything and quit the army service. And it turned out that he did this one year and a half before he could retire and get his pension, and for this reason he did not get a kopeck for all his military service. And as far as I remember our family arguments at home, he used to say to mother all the time: ”It was because of you that I forfeited my pension”. And she always answered him: “Why a smart guy like you did not tell me that you only had one and a half years more to go to be entitled to a pension?” He returned to Kharkov having nothing, having no profession. He was about 30… He looked for a job, suffered, then he found a job at a factory. Mother found a job there, too. Then she graduated from a vocational school and after this my brother was born.

Y: Were they an assimilated family?

T: Undoubtedly, yes… there was nothing Jewish besides Grandmother in our home.

Y: Did it somehow influence the atmosphere at home?

T: No way. She was a usual woman, a simple one, not very educated… She knew how to cook gefilte fish, how to speak Yiddish.

Y: And did you know your Granddad?

T: No, he died when my mother was 5. And Grandmother was widowed most of her life.

Y: This means that she was a natural carrier of the Jewish tradition but nothing more. It did not establish itself in the family.

T: Yes. But for example, on Pesakh as long as I remember myself Grandmother used to bake matzoth. And when I became older I helped her with that. We also made hamentashen. And suddenly, when she was close to her 60-s already, she found some Jewish old men and there was a minian there. And she started to attend that place, and to observe some of the mitzvas. Suddenly it turned out that she could eat some things and could not eat other things… But she died soon after that. Her old men buried her according to the Jewish ritual.

Y: It is very difficult to feel not Jewish with your last name Feivert. How did it affect you?

T: But you know what they used to tell a kid in a Jewish family. If you want to feel normal you have to be two heads higher than the others.

Y: And at school?

T: And there was a class journal at school if you remember, and it there on the last page nationalities of all children were written. I was the only Jewess in the class I believe.

Y: You felt this.

T: Undoubtedly I did and was called “kike” repeatedly behind my back. This helped me develop a good walk. You had to always walk keeping your head up high proudly and square-shouldered and pretend that you do not care what is said behind your back. Then I went to college, and I had some Jewish friends there. When you try to understand why on earth the society drives you into a corner in a sense, you start looking for something else. The most surprising revelation for me was that Marx was also a Jew. Yes… Our Grandmother was also notable for watching TV and finding out who on the screen was a Jew and who was not. We read books… And whenever we discerned some Jewish accents, it always interested us.

Y: What did your parents want from you, did they prepare you for a certain kind of life?

T: They could not make me a Russian, they were not idiots, were they? They wanted me to be well when I grow up. And I had to get education for that. There were no Jewish accents there. The only thing that for some reason grandmothers and mothers managed to put into Jewish girls’ heads was that they were supposed to have Jewish husbands. Why, I do not know.

Y: And you had this knowledge in you, too.

T: Somehow it stays inside you. I do not know why. The only thing from all this tradition that comes into your head is that you must marry a Jew.

Y: And what was it that led you to Zionism?

T: This is a very personal story. It developed because of my first husband. There was more Jewishness in their family. They spoke about it more often. We knew each other long enough, since 1970, and we got married in 1974. Our parents knew each other well also. Gena Rabinovich, this was my first husband’s name, studied in college, at an evening department. His father had a difficult life, with a penal battalion and forced labor camp behind him… This was why Gena was born somewhere in Ust-Kaminsk, near the labor camp where his father served his term. He had to serve in a penal battalion for being three days late at his military unit, he was an army officer then. He was immediately demoted and he served as a private in the penal battalion. He was released from the penal battalion for having brought in a prisoner for interrogation. And he served a term in a forced labor camp for selling a bag of potatoes after the war… He bought and sold it, and was caught, so he was sent to the labor camp right away, because he had this penal battalion on his record already.”

Y: So, such was your first husband’s family then. Did he have any Zionist moods?

T: No, he was a normal good Jewish boy, without any special inclinations. But in 1972 my cousin in Kiev left for Israel and then it was the first time that the question arose – and what about us, what should we all do? And we discussed this topic at length. At that time I was flatly against leaving the country. It was incomprehensible to me and it did not tell anything to my heart. Gena’s father wanted to leave already at that time, and he spoke about that. When we got married the issue of our leaving the country became more serious. At that time I was already working at an aircraft plant, I got this job through good connections, otherwise it was difficult to get a position there with my [Jewish] last name. I worked there for 5 years till 1978. During this time I had a daughter, and my husband’s parents started to press on me to quit my job because I had a security clearance there and it was quite possible that they would not be allowed to leave because of me. I did not so much want to leave at that time but I started somehow to get used to the idea. They filed their applications in 1977. In order to let them leave, we got divorced… but we were planning to get married again later. If they were normal parents they would have left by themselves and we would join them later. But it was characteristic of my first husband to always place his parents’ interests above everything else. “Mother and Father said that they are not young anymore and that they can not leave by themselves…” Gena had a brother also but he was not reliable enough in his parents’ opinion. By this time he was already married for the third time. And they decided that my husband was just the right person to rely on. He left and they lived in Gilo in Jerusalem at first, and then they moved to Tsfat and there they lived and worked in HiTech companies. I found another job, applied for an exit permit in 1979 and got a refusal, naturally, because I did not have close relatives in Israel! At some point during this time I met you in Moscow. When my husband was leaving, he introduced me to someone called Felix Kharlam. Felix was then recruiting a group [for studying Hebrew] and I started to study Hebrew there. Then about half a year later I asked him why we stopped making any progress in our studies. And he told me confidentially that he himself did not know anything beyond what we had already learned. He said: “I was in Moscow and there I was taught the first ten lessons only”. He studied somewhere there with you. “You do not work, you have nothing to do, so go to Moscow”. He came along with me and Sasha Ostrovskij took him and me to your place. This was how we met at your place in 1979. You said: “OK, you come over here for a month and we’ll teach you”. I had a relative who was in refusal. I stayed with her. When I came over to your place you asked me where I was staying and it turned out that I stayed in the same building where Yura Stern lived. So you suggested that I study with him. Yura worked at the University at that time. He had relatively a lot of free time and for a month and a half he taught me everyday. And those were long lessons, of 5 or 6 hours. It was in spring 1980. I attended your dibur. On the Day of Jerusalem we all went to Ovrazhki, there you introduced me to an American Physicist of Israeli origin, his name was David and by then he had been working in America for many years already. And I spoke Hebrew with him, that Hebrew of mine that I studied for a month and a half with Yura. But nevertheless we still could speak about something. And then you took another man, whose name was Yulik Edelstein, by the hand, led him to me, and said to him: “Let me introduce you to a girl who has been studying Hebrew for a month and a half only and she is talking and talking already… she has just spoken with an American guy about something for half an hour!“. This is how I met Yulik. I saw him at diburs before of course but this time I had a chance to know him better. Then we went to Gorodila, and David came along with us and he got totally drunk there and started yelling some ditties in Hebrew, and then with great difficulty we put him on a bus. And ever since that “Day of Jerusalem” I have been with Yulik. We always celebrate this day as the day of our acquaintance. Since that time we have been together 24 years, thank God. And then Yulik was a Hebrew teacher [in Moscow], and I went to Kharkov to teach Hebrew, I had my own Hebrew groups there. From time to time there were problems with KGB men. Yulik used to come over to us to teach the advanced groups. Then for a couple of years we were organizing canoe trips for the advanced student groups to intensively practice Hebrew there– these were the summers of 1981 and 1982. In 1980 as you remember I was in Koktebel at the training courses for teachers. I studied in Yulik’s group. A couple of weeks later they detained you while you were jogging. We lived in a little house with a yard and late Borya Berman lived nearby, and KGB men were sitting behind the fence in the neighboring yard and they, too, had meaningful conversations – how one speaks Hebrew with a Ukrainian accent and how with a Russian one. It turned out that we lived there simply surrounded by the KGB men and it was funny to notice it. We sat on the beach and studied Hebrew and they sat in 10 meters from us getting a sun-tan. Thus it continued nicely and ended up with your arrest. We all left, feeling somehow nervous. Before I left for Koktebel they summoned me to the OVIR. And they made an appointment for me not at their regular hours. When I came over there the OVIR was closed. But they let me in and two persons talked to me. One as far as I understood was my KGB curator. He did not introduce himself, and the other was the head of the OVIR. And they told me: “Here, we are looking through your file now, sit down and write a report for us about things you worked with. Maybe you had a security clearance for no particular reason and you had actually no contact with classified information, in any case, just write a report. And since we are going to make a decision on your case right now, it is very important that you stay here at your place because we may give you our reply today or tomorrow. You are not going anywhere, are you?“ And I had a ticket to Koktebel for that evening. They said: “Take into consideration that if you go somewhere you can do much harm to yourself because we are examining your case right now”. I said: “Of course, of course”, – returned home, then boarded my train and went away. Then I did not hear from them anything and a month and a half later they summoned me and handed me an official refusal. They loved to speak to my father. In May 1981 we went to Minsk for several days. Before we left two people came over to my dad’s work and said: ”You have such a restless daughter . You’d better stop her from going anywhere, or else she may go somewhere and you know how it can happen on a trip… she may fall from the train… she may break her legs and arms…” But it was OK, nobody broke anything. And again I just said the same “Of course”- and left.